In September 2008, in preparation for a 2009 National Geographic documentary called 'Hitler's Stealth Fighter', a team of engineers from Northrop Grumman dusted off the last surviving airframe from a Horten Ho 229 V3 prototype Nazi bomber design at a Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum storage facility in Maryland to engage in testing of the aircraft's stealth properties.

Building a mockup of the aircraft using "modern techniques," including stereo-lithography, engineers were able to simulate its performance against period British Chain Home radar network components, designed to help ward off Luftwaffe attacks.

The project was given serious consideration, with testing carried out at a California-based radar cross-section (RCS) test facility, with imagine techniques "utilized to understand the main RCS scattering sources of the Horten 229 V3," according to the museum.

Their findings, presented in 2010 at an aviation conference in Texas, proved somewhat disappointing.

As National Interest contributor and Ho 229 enthusiast Sebastien Roblin recently wrote, the Nazis' "flying wings would have been detected at a distance 80 percent that of a standard German [Messerschmitt] Bf. 109 fighter," a stock fighter design introduced in 1937 which served as the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter forces during the war.

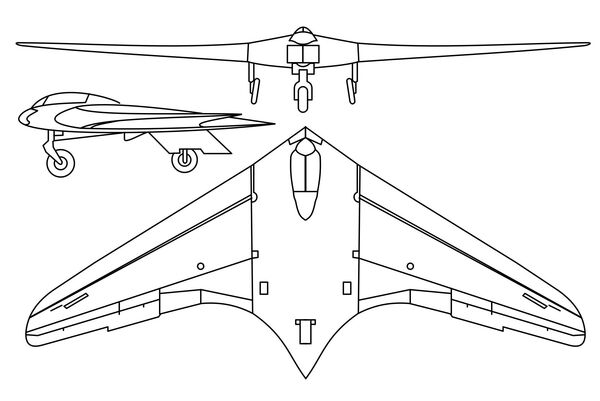

The Ho 229 design was created by the Horten Brothers, a pair of Luftwaffe fighter pilots who previously served as design consultants to aircraft manufacturers during the early war.

Luftwaffe supreme commander Hermann Göring laid out the design specifications for the plane in 1943, requesting that it be capable of flying 1,000 km per hour, have a range of 1,000 km, and be capable of carrying 1,000 kg-worth of bombs. The design was aimed at outrunning enemy fighters, and was put forth amid the devastating losses faced by the Luftwaffe bomber force on both the Western and Eastern Fronts by this point in the war.

The revolutionary flying-wing shaped design was aimed at dramatically improving the Ho 229's aerodynamic properties to save fuel and increase its speed, and was returned to by the US military designers (but with stealth, rather than fuel conservation and speed, in mind) in the 1980s.

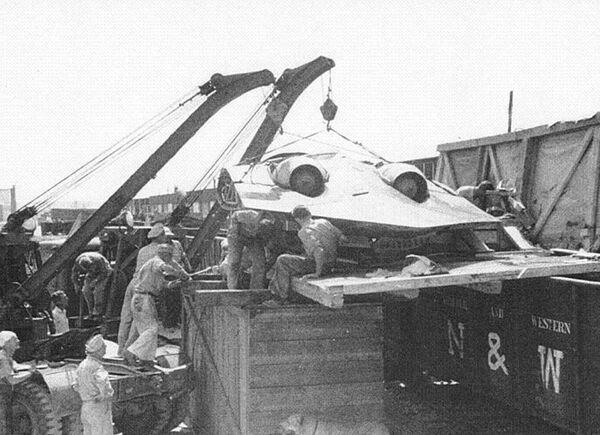

Never leaving the prototype stage by the end of the war, the Ho 229 did not become one of Hitler's 'Wunderwaffe' or 'Miracle Weapons' meant to turn the tide against the Allies. However, the bomber design did receive intense interest abroad, with the US military launching Operation Paperclip, aimed at snatching up Nazi weapons technology, including the Ho 229, to prevent it from making it into the hands of the US's erstwhile Soviet allies.

Interestingly, just one year after the Ho 229 program's designs made it into the hands of US engineers, Northrop Corporation unveiled the YB-35, a flying wing bomber design fitted out with turboprop engines incredibly similar to the German plane. Like many aviation powers at the time, Northrop had been experimenting with flying wing designs since the early 1940s, and it remains unclear just how much influence the Ho 229 design had on the YB-35 program, which was canceled in 1949 due to a bevy of technical problems.

In their 2008 tests, Northrop Grumman engineers did find that the Ho 229's main design feature – speed, could have proven devastating to the Allies if fielded in time. As Roblin recalled, the Ho 229's speed "could have exceeded the maximum speed of the best Allied fighters of its time by as much as 33 percent," meaning that even though the planes could have been spotted by radar, "detection time would not have mattered greatly if it could outrun everything sent to intercept it."

Indeed, in a 2016 interview, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum aeronautics curator Russell Lee said the bottom line of the Northrop Grumman engineers' 2008 study concluded that "they couldn't say the aircraft was any stealthier than a regular sheet of plywood."