An international team of scientists comparing observations made by two separate spacecraft taken a day apart in 2013 have finally conclusively confirmed the presence of methane on Mars, following over a decade and a half of speculation after an ESA probe discovered the existence of trace elements of the compound on the Red Planet.

The study, led by Dr. Marco Giuranna of Italy's National Astrophysics Institute, examined measurements from NASA's Curiosity rover and Europe's Mars Express taken a day apart in June 2013, definitively showing the presence of trace amounts of the compound in the atmosphere above the Gale Crater, a 154 kilometer-wide formation located along the Martian equator and previously considered to be a dried out lake.

"This is very exciting and largely unexpected," Dr. Giuranna said, speaking to AFP. "Two completely independent lines of investigation pointed to the same general area of the most likely source for the methane," he noted.

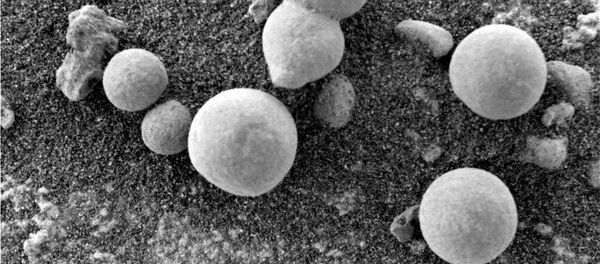

In addition to confirming the presence of methane, the planetary scientists ran computer models to try to figure out its source, dividing the region around the Gale Crater into 30 250x250 km2 grids. This led them to conclude that the methane probably came from underneath a rock formation, where it is frozen in solid sheet form and sporadically released.

In any event, the scientist stressed that methane "can add to the habitability of Martian settings, as certain types of microbes can use methane as a source of carbon and energy." Ultimately, Giuranna noted that if large quantities of methane can be found, the compound could help "support a sustained human presence" on Mars, including as a possible source of fuel, both for construction and as a propellant for spacecraft shuttling to Earth.

This important discovery follows the release of photos by the veteran Mars Express atmospheric research orbiter last month showing that Mars may have once had a great deal more water than previously anticipated, with topographic images indicating an entire network of branching, dried out trenches and valleys thought to have once held the liquid, which is another necessary condition for carbon-based life.

Giuranna et al.'s findings were published in this month's Nature Geoscience journal.