Soon after his appointment as UK Permanent Representative to the Atlantic Council [NATO's governing body — NG] in early 1992, Sir John Weston offered his "First Impressions" of the challenges facing NATO to the then British Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd.

Betraying a poetic streak in his character that fully manifested itself after his retirement from the diplomatic service, Sir John addressed the mundane topic of geopolitics in highly elated terms:

"The Alliance (once described by Bevin as a "spiritual federation") has much in common with the Church, and all Allies must be her votaries".

Referring to NATO's regular summits, Sir John elevated them to the status of religious "festivals observed with solemnity".

"…the front seats occupied by the good and the great. Ritual generally still takes precedence over spontaneity. Variations of traditional behaviour in the pews are discouraged. Devotional exercises are expected to stop well short of moving and shaking".

"When there is no crusade to animate the faithful, especially the wider body whose tithes are so essential to ecclesiastical upkeep at home and missions abroad, doctrine comes under renewed scrutiny and external processions fall off".

And so Britain embarked on a crusade to save NATO from… its members.

In 1991-93 NATO was in disarray, the allies had widely divergent views on the future of their alliance.

READ MORE: 'You Need to Have an Enemy': NATO's Endless Expansion Keeps Weapons-Makers Flush

The US Congress wanted to cut the military budget and bring US troops in Europe back home, the French were peddling the idea of a pan-European security arrangement independent of the US, the Germans wanted all foreign troops — and nuclear weapons — off their soil.

The Italians were not far removed from the Germans in their feelings. All this was anathema to London. After all, it was the British desire to "keep the Russians out, the Germans down and the Americans in" Europe, in the famous adage of NATO's first Secretary General Lord Ismay that led to the creation of the North-Atlantic military bloc 70 years ago. Any illusions that NATO was a political body were dispelled by the UK envoy:

"…a visit to military headquarters in the field such as Ramstein… is a reminder that whatever the emphasis at the moment NATO is at heart a great military alliance or it is nothing".

But to Sir John Weston the threat was obvious, he could sense "a creaking of tectonic plates beneath Alliance ground".

"There are… strong forces at work to disengage the United States from its post-war European attachment".

Indeed, the first reaction of the British government to the end of the Cold War was "how can we persuade the US to keep its 100,000 troops in Europe now that the threat is gone"?

READ MORE: UK RAF Official Warns NATO: F-35 Won't Solve Our Problems

Britain's ambassador cabled from Washington: "Most pro-NATO figures in the Senate strongly doubt whether it would be possible to retain support here for 100,000 US troops in Europe unless the Alliance can show its relevance to Eastern Europe. They see a danger otherwise of NATO ending up with no real content".

To Sir John Weston anyone questioning the rationale for the continuing presence of US troops in Europe was a "sorcerer's apprentice on the loose". He cited a poll in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung showing that more than half of Germans questioned wanted American troops to leave Germany by 1995, after the final withdrawal from the country of former Soviet forces. Sir John saw "sorcerer's apprentices on the loose" in Bonn and Paris, a clear reference to their plans to establish a Franco-German nucleus of a future European Army.

"Despite soothing and mantra-like expressions to the contrary around NATO tables, I sense that some partners risk being increasingly tempted along the so-called Third Way by the Franco-German initiative".

NATO, in Sir John's view, was suffering from "a basic loss of direction" in the "absence of sufficient consensus among the four major allies".

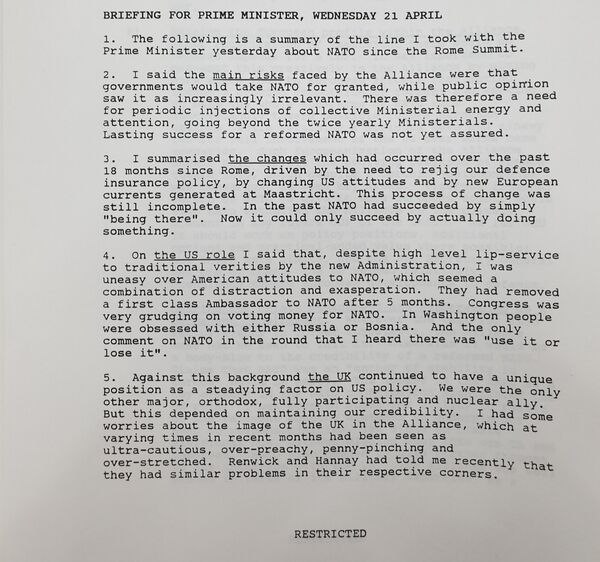

Briefing PM John Major in April 1993 on the US role Weston said that, despite high-level lip-service to traditional verities by the new Administration, he was "uneasy over American attitudes to NATO, which seemed a combination of distraction and exasperation".

"Congress was very grudging on voting money for NATO. In Washington, people were obsessed with either Russia or Bosnia. And the only comment on NATO that I heard there was "use it or lose it".

Sir John suggested London should "chart an early course for the Clinton administration" to follow. The UK, he said, continued to have a unique position as a steadying factor on US policy, being "the only other major, orthodox, fully participating and nuclear ally". As for other European members of NATO, they needed to be worked on by London to bring them into line. The French had to be coached to abandon a "certain schizophrenia" towards fuller reintegration into NATO military structures that they had left in 1960s.

"The UK should also work on the Germans over wider Euro-Atlantic themes. Need to provide ballast against the German tendency to look eastwards. The Euro-Atlantic Community is certainly a more convincing vision than a pan-European concept that attempts to embrace the Eurasian landmass all the way to Vladivostok. It does not exclude extension Eastward as circumstances permit; and should certainly find room for Japan".

READ MORE: US to Present NATO Ministers Surveillance Package to Counter Russia in Black Sea

However, the German Chancellor Helmut Kohl saw no case for an early enlargement of NATO. In an interview on German TV in October 1993 he said while no country in Europe had done more for the Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, and Hungarians to support their aspirations to join the European Community [now EU], there was "absolutely no case in current circumstances for saying that they must now become part of NATO".

In response to Russian President Yeltsin's letter about Russian sensitivities regarding the expansion of NATO, UK PM John Major reassured Moscow that:

"there would be no rush to bring new members into NATO. But London attached high importance to bringing countries such as Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic into the European Community as soon as they were ready".

Privately though, the British expected every new member of the EC [EU] to join NATO. The Foreign Office advised the PM that "there was already a link established between Community membership and NATO membership".

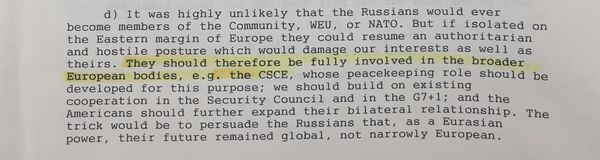

But for Russia, who broached membership in Western institutions on several occasions, the odds were firmly against it, as Sir Rodric Braithwaite, Prime Minister Major's foreign policy adviser and chairman of the UK's Joint Intelligence Committee opined in July 1992,

"it was highly unlikely that the Russians would ever become members of the Community, WEU [West European Union —NG], or NATO… The trick would be to persuade the Russians that, as a Eurasian power, their future remained global, not narrowly European".

READ MORE: Former UN Arms Inspector: Europe as Much to Blame for Demise of INF Treaty as US

Russia, apparently, took this seriously only to be denounced by the West for its "global ambitions".

NATO was reserved, in the words of the UK Envoy, to be "the most effective vehicle for North Americans to exert influence in European questions also central to their own long-term concerns". But,

"The Alliance requires a constant energy input if its thermodynamic potential is not to ebb. It will decay as a result of external factors if it is not continually charged up and changed from the inside".

There will be a lot of celebrating at NATO's 70th-anniversary celebrations in Washington this week. But what can the NATO allies produce to support their claims of success? Bombed out Yugoslavia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, rising tensions in Europe, or a looming nuclear arms race?