Twenty five years after the infamous genocide in Rwanda, there are still a handful of top fugitives from justice out there.

A US$5 million reward is still being offered by the US State Department for "individuals who furnish information leading to the arrest, transfer, or conviction" of Felicien Kabuga, a wealthy businessman who had bankrolled the genocide by importing 500,000 machetes.

In 2002 they came close to catching Kabuga.

An informant set up a meeting with him in Nairobi, Kenya, and hopes were high that he would finally be caught.

— Human Rights Watch (@hrw) 4 April 2019

But somehow he caught wind of the trap, the meeting was cancelled and the informant ended up dead.

Kabuga, who had funded the "hate radio" station Radio Television Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM), fled Rwanda in June 1994 as the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) rebels advanced on Kigali.

He flew to Switzerland but was expelled before his importance was realised. He arrived in Kinshasa and eventually made his way to Kenya, where he is believed to be still in hiding.

In 1997 he slipped away when several other exiled Hutu leaders were arrested and in 2007 German authorities apparently came close to catching him in Frankfurt.

He is now 83 years old but is thought to retain access to a large amount of money, which he uses to pay off corrupt Kenyan politicians and other officials.

Rogues' Gallery — Each With $5Mln Reward on Their Heads

Others with $5m bounties on their heads include Protais Mpiranya, Augustin Bizimana, Sylvestere Mudacumura, Fulgence Kayishema, Pheneas Munyarugarama, Charles Sikubwabo, Aloys Ndimbati, Ladislas Ntaganzwa and Charles Ryandikayo.

During the genocide Mpiranya, now 69, was commander of the Presidential Guard within the Rwanda's army. He is alleged to have directed the Presidential Guard in sexually assaulting and killing Rwandan Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana and murdering ten Belgian UN peacekeepers.

Bizimana, now 64, was Defence Minister in the Rwandan government and is accused of preparing and planning for the Rwandan genocide between 1990 and 1994, including fostering ethnic hatred and preparing lists of people to be exterminated.

Ethnic tensions between the Hutu and Tutsi had troubled Rwanda for decades.

The Tutsi — generally taller and thinner than the Hutu — were originally cattle herders from the Nile valley who came to Rwanda and by the 19th century were lording it over the Hutu, who were subsistence farmers.

Festering Hatred Towards the Tutsis

The Tutsi aristocracy collaborated with German and French colonial rulers and a seething resentment festered under the surface for decades, even after Rwanda became independent in 1962.

Habyarimana became President in 1973 and in 1990 the RPF began an insurgency, which coincided with the rise of a sinister movement, Hutu Power, who had already decided on a "final solution" to the Tutsi problem.

It is thought the missile which brought down Habyarimana's plane was probably fired by RPF rebels, led by Paul Kagame, who is nowadays President of Rwanda.

In a controversial book the former Rwandan ambassador to Paris, Jean-Marie Ndagijimana, claims Kagame deliberately sacrificed the lives of 800,000 Tutsi for political gain.

Rwanda's first President, Grégoire Kayibanda and his wife were starved to death by his friend and Defense Minister, Juvénal Habyarimana, who overthrew him on July 5, 1973. They were kept in a secret location.

— Africa Facts Zone (@AfricaFactsZone) 13 March 2019

Habyarimana himself was later assassinated in a plane attack in 1994. pic.twitter.com/u4lAa7zcMD

Ndagijimana's conspiracy theory runs that Kagame knew shooting down the plane would trigger the genocide, which he knew would make the Rwandan regime unpopular among western nations, allowing the rebels to sweep in as "liberators".

Ndagijimana goes on to claim the RPF carried out their own massacres of Hutus in the summer of 1994 after coming to power.

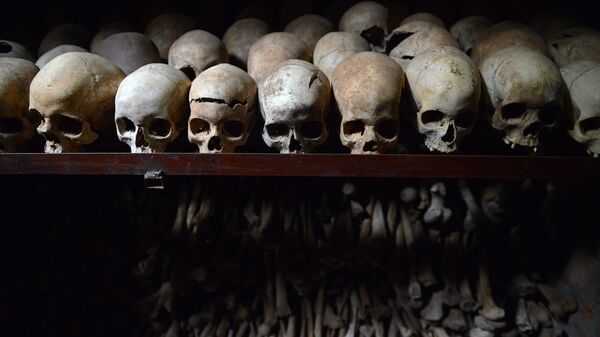

But whether or not there is any truth in Ndagijimana's claims it does not justify the genocide of hundreds of thousands of Tutsi men, women and children by the Interahamwe militias as well as around 200,000 moderate Hutus.

Hutu Power described the Tutsi minority as "inyanzi" — meaning cockroaches — and called on Hutus to wipe them out.

Hutu Power were led by a group, known as akazu, who were closely related to Habyarimana's widow, Agathe.

France's Guilty Secrets Over Genocide

She fled to Paris after the RPF came to power and remains there today, arguably protected by the French government because of what she knows about the activities of the Quai D'Orsay, the French foreign office.

Mrs Habyarimana is now 77 and in 2011 a French court refused to extradite her to Rwanda.

Throughout April, May and June ordinary Hutus, whipped up by Interahamwe and Rwandan soldiers and often intoxicated, rampaged through the country slaughtering Tutsis, usually with machetes or other household or field implements.

The international community was infamously slow to respond and several Belgian UN peacekeepers lost their lives when they tried to protect Tutsis.

— Mansoor Bernal Leyda (@AkhMansoor) 5 April 2019

The system of bringing Rwandan war criminals to justice began soon after the RPF took control of Kigali.

Death sentences were handed out on a number of notorious individuals, including Froduald Karamira, who had worked under Kabuga at RTLM, whipping up ethnic hatred over the airwaves.

One day in April 1998 a firing squad despatched Karamira, 20 other men and one woman in front of a baying crowd of 7,000 people.

But Rwanda decided soon after that the death penalty was inappropriate and, with former Interahamwe hunkered down in refugee camps across the border in the Democratic Republic of Congo, there was a danger of creating martyrs to the Hutu Power cause.

Some Ringleaders Serving Jail Time in Mali

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) had been set up across the border in Arusha, Tanzania and in October 1998 its first trial ended, with Jean-Paul Akayesu, a Hutu mayor, jailed for life. He is serving his sentence in a prison in Mali.

Akayesu's trial was the focus of a 2015 film, The Uncondemned.

The ICTR has dealt with 75 cases from Rwanda — 12 of whom were acquitted.

A handful, such as Jean Kambanda, who was prime minister of Rwanda from 8 April until 17 July 1994, pleaded guilty.

Kambanda, now 63, is also serving his sentence in a jail in Mali.

Many more Rwandans were dealt with by the so-called gacaca courts.

The genocide had been so widespread that by 2000 Rwanda's jails were heaving with around 120,000 suspected war criminals awaiting trial.

Village Justice — and Forgiveness

Kagame's government decided to set up gacaca courts — the word means short, clean cut grass in the Kinyarwanda language used by both Hutus and Tutsis — which met in villages and meted out a form of traditional justice, based on testimony from those who survived.

Eventually around two million people went through the gacaca process and 65 percent were found guilty.

Some were sentenced to long jail sentences, with hard labour, but many were simply sent back to their villages and told to rebuild their communities along with relatives of the victims.

Many victims' relatives were persuaded to forgive the killers, who often have become their neighbours again.

But many genocidaires — as they are known — escaped justice entirely, often by fleeing abroad.

Some lied about their role and even claimed to be victims themselves.

In July 2013 Beatrice Munyenyezi, 43, who had fled to the US in 1998, was convicted of lying about being a genocide victim in a bid to get refugee status.

Far from being a victim, Munyenyezi had actually commanded a roadblock near Butare where victims were picked to be murdered. She was jailed for 10 years in New Hampshire.