In an announcement scheduled for Wednesday, April 10, at 9 a.m. EDT (1300 GMT), the US National Science Foundation in Washington will release a "groundbreaking result from the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) project," according to multiple reports.

The EHT project, an international scientific collaboration, was formed in 2012 as a means of directly observing the area immediately surrounding a black hole.

Concurrent announcements are set to occur in Tokyo, Brussels, Taipei, Santiago, and Shanghai, according to the EHT website.

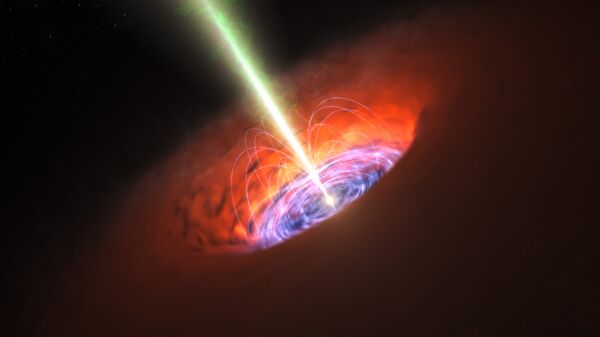

One of the most intriguing of spacetime environments, the region around a black hole — described as the ‘event horizon' — is also one of the most violent in the known universe, as matter inexorably hurtling into the dark maw is mangled to what scientists guess to be the subatomic level, while light itself is rendered permanently captive, leading to the celestial singularity's picturesque name.

"It's a visionary project to take the first photograph of a black hole. We are a collaboration of over 200 people internationally," asserted astrophysicist Sheperd Doeleman, EHT director at the Center for Astrophysics, Harvard & Smithsonian, in March, cited by Reuters.

The new findings will test legendary physicist Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, according to EHT project astrophysicist Dimitrios Psaltis.

To conduct their discoveries, the EHT looked at two supermassive black holes: Sagittarius A* at the center of our Milky Way galaxy and M87, at the center of nearby galaxy Virgo A.

Sagittarius A* is measured as being some 26,000 light years from Earth and massing approximately 4 million times that of our sun. Virgo A is calculated to be some 3.5 billion times the mass of our sun and situated about 54 million light-years from our solar system.

The new observations will be used to detect evidence of what happens at the edge, or shadow, of a black hole, particularly as Einstein's predictions — if correct — permit accurate measurements of the object's size and shape.

"The shape of the shadow will be almost a perfect circle in Einstein's theory," Psaltis stated, adding, however, that "if we find it to be different than what the theory predicts, then we go back to square one and we say, ‘Clearly, something is not exactly right,'" cited by Reuters.