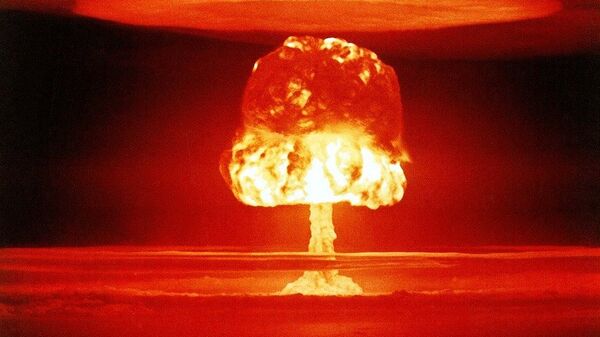

Nuclear conflict remains the greatest threat to global security, yet despite the importance of stable nuclear policy to US and global safety, one clear avenue for improvement has been neglected: Getting more women in the field, writes Foreign Policy observer Xanthe Scharff.

"Men make nuclear weapons more dangerous. So why do they still dominate the field?" asks Scharff, co-founder and executive director at the Fuller Project for International Reporting.

Men make nuclear weapons more dangerous. So why do they still dominate the field? #FletcherAlum @XantheScharff (F06, F11) argues for the importance of having women in the room during critical #nationalsecurity decision-making. https://t.co/KHaDJKqnEL @FullerProject @ForeignPolicy

— The Fletcher School (@FletcherSchool) April 16, 2019

Scharff referred to a study by the Royal Society that showed men in simulated wargames scenarios are more likely to demonstrate overconfidence than women, thus signalling the indisputable benefits of ensuring that women are fully represented in high-level policy roles.

The same study showed that overconfidence in high-stakes conflict scenarios is more likely to lead to a decision to attack a perceived enemy.

However, according to Scharff, women represent only about a quarter of delegates in international nonproliferation talks.

Xanthe Scharff cites a study carried out by New America think tank that interviewed 23 high-level US female policymakers regarding their experiences in the nuclear field. They rejected the idea that “women are more dovish and men more hawkish," but reported that when women were present in policy discussions, collaboration was valued over competitiveness and innovation was more welcome.

Nevertheless, women continue to hold relatively few leadership positions in US policymaking in the nuclear field, as shown in a graphic that was researched and developed by New America. Between 1970 and 2019, only 11 of the 68 people who held leadership positions in the Department of State were women, as well as just five out of 36 at the Department of Energy and five out of 63 at the Department of Defense.

READ MORE: US Astronaut to Spend Almost Year Aboard ISS, to Set New Women's Record — Source

Indisputably, says the study, women in nuclear policy face tremendous barriers, including lack of recognition. “There’s no shortage of women [in nuclear policy] … it’s fighting for the airspace to get included when there’s an interview to be done,” said Nancy Parrish, the executive director of Women’s Action for New Directions, an anti-nuclear activist organisation that leverages women’s political power to advocate for peace.

Think tanks also need to examine their practices with an eye toward more recruitment and promotion of female leadership, believes Scharff.

Congratulations to Katie Bouman to whom we owe the first photograph of a black hole ever. Not seeing her name circulate nearly enough in the press.

— Tamy Emma Pepin (@TamyEmmaPepin) April 10, 2019

Amazing work. And here’s to more women in science (getting their credit and being remembered in history) 💥🔥☄️ pic.twitter.com/wcPhB6E5qK

A scorecard published by Women in International Security in 2018 found that 73 percent of experts in Washington think tanks are male, 78 percent of think tank governing board members are male, and only one of the 22 surveyed institutions had significant gender-related programming. Some women report that gender bias is particularly strong in think tanks.

Clearly, changes in women’s representation in nuclear policy are justified as a matter of social justice—but also much more, concludes Xanthe Scharff, since nuclear security is the field with the highest stakes of all and “the world can’t afford to push innovation and talent out”.