Using data gleaned by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, the revised age and expansion estimates from Nobel Prize-winning astronomer Adam Riess brought the standard model of physics to a momentary halt, as scientists around the globe ponder the implications of the new information.

Our faster and younger universe is estimated by the use of a mathematical calculation known as the Hubble constant, a number defined in the early 20th century but now — thanks to Reiss and his new research — claimed to be some 9 percent higher than previously stated.

The new number directly affects humanity's ability to guess at the age of the known universe, an integral physics calculation.

"It's looking more and more like we're going to need something new to explain this," noted Riess, a Johns Hopkins astronomer who won the 2011 Nobel Prize for physics.

Other scientists, including NASA astrophysicist and nobel winner John Mather, suggest two options to the cosmic conundrum: "One, we're making mistakes we can't find yet. Two, nature has something we can't find yet," according to the Deseret News.

Currently, most astronomers are confusingly suggesting that both Riess and the earlier model may be right — at the same time — particularly as "nobody can find anything wrong" with either measurement, according to University of Chicago astrophysicist Wendy Freedman, cited by KWTX.com.

"You need to add something into the universe that we don't know about," noted Carnegie Institution for Science astrophysicist Chris Burns.

"That always makes you kind of uneasy,' he added, cited by Deseret News.

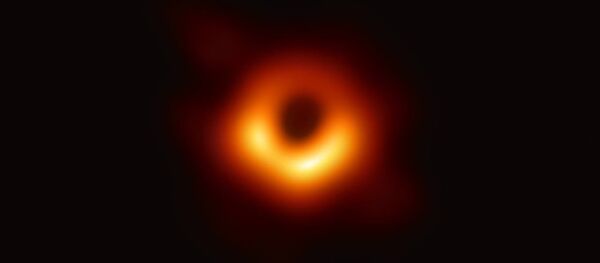

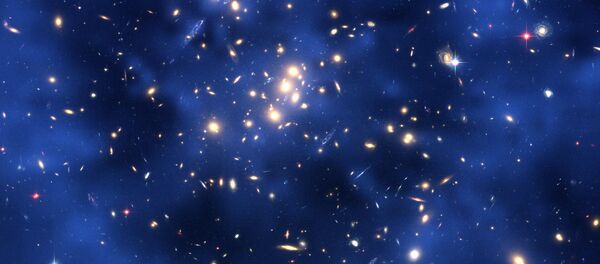

Whether dark matter, dark energy or another as-yet-undiscovered elemental force comes into play to explain how two results can be right at the same time, astrophysicists will still need to make changes in Einstein's general theory of relativity, a towering intellectual accomplishment recently supported in photographs taken of a black hole in galaxy M87.