Sputnik: Sri Lankan authorities banned social media after terror attacks. In your opinion, will this measure help in tackling the current crisis in the country?

Paul Levy: There are a number of possible drivers behind this. With Facebook recently announcing it will take down pages that contain "far-right content," and promising to also improve its banning and blocking of terrorist groups and those supporting and inciting terrorist acts, but also at the same time coming under criticism for not doing enough (not just Facebook but other social media platforms), trust in social media is at an all time low. The banning of social media will have limited effect as such individuals and groups will find other means to communicate. Certainly the sharing of shocking images and video material can be limited at such sensitive times.

Governments also want to be seen as acting and responding quickly, and the blocking of social media during such a crisis is a clearly visible demonstration that governments are trying to act quickly. The downside is the limitations this sets on others simply trying to communicate, and share during such difficult times.

READ MORE: Rabbi Blames US Synagogue Attack on Social Media 'Encouraging Lone Wolves'

Sputnik: Social media is often faster and more flexible in delivering breaking news, especially in the case of tragic events such as terror attacks or natural disasters. Wouldn't it be more helpful to the public to know if something is happening nearby, than to deny access to that information?

Also it perhaps doesn't need to be all or nothing. The ability to mark yourself as "safe" in a geographical danger zone, is a very innovative and valuable tool on social media. Perhaps some tools of social media become more valuable, and a blanket ban is too clunky and draconian.

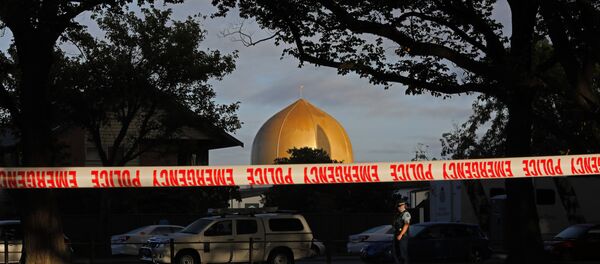

READ MORE: New Zealand Ban on Christchurch Mosque Shooter’s Manifesto Electrifies Twitter

Sputnik: There's also a lot of talk about stricter regulations for governing content. For example, at the time of the Christchurch attack in New Zealand, there was an outcry from users that a lot of harmful content was spread — images of the attacks, plus the criminal's account and manifesto were in the open field. How should social media platforms react in cases like this?

Paul Levy: Social media platforms, like any spreader of news have a duty not to promote terrorism. The spreading of a first person video of mass murder is unacceptable in our societies (surveys and polls confirm that) and platforms such as Facebook have recently admitted that they cannot be content-neutral. It is their responsibility to ensure our children are safe and that content is not obscene, racist, dangerous to life etc. It is now as much about being proactive and preventive than being quickly reactive. Stopping content appearing in the first place is much better than trying to prevent its spread, because the basic building blocks of social media are to encourage sharing and spreading.

They are employing more people to scrutinize content, as well as looking to Artificial Intelligence to be much smarter in identifying unacceptable content in real time, or even before it is posted and shared. None of this is perfect. In many ways, this is no different to what happened before social media existed. It is difficult detective work.

Sputnik: We often see reports that the US, Europe and other countries have vowed to impose stricter regulation of these platforms. What could be the possible reason behind this?

Paul Levy: This is not just the US, Europe and other countries. This is becoming a global call. When social media (either willfully or accidentally) cross the same boundaries that are set offline, they can be held to account even more, because social media is so fast, widespread, and involves children so much. People have human rights {guaranteeing} safety, the ability to access truthful news, and even to not be manipulated by corporations or governments. Children have the right to be safe, and organisations must safeguard them. Food and medicines should be safe etc. This is true on or offline.

With so many cases of these things not always being consistently upheld, governments are turning to legislation which challenges the mission of a "free internet". Not all governments are trusted, be they anywhere on our planet, so one major problem is that the regulators and their motives are not entirely trusted either — in all, pretty much all countries, from all corners of the world.

READ MORE: Trump Meets With Twitter CEO Dorsey to Discuss Social Media

Sputnik: Social media is also influencing politics. Experts say that Donald Trump's Twitter account was one of the key elements in helping him win the presidential elections in 2016. In your view, to what degree do tech platforms integrate into the wider political field?

Paul Levy: They have been accused more of this in the last two years, than in the entire history of the online world. This question mentions Donald Trump. But to answer this question fairly we would have to mention Russia, China and many other questions. As Sputnik — will you publish the answer to this question in its entirety? All governments, if they care for the genuine right to free choice and thinking at the ballot box, would have to be held to account for any influence they try to gain over voters in their own and other countries.

Should politicians and presidents, prime ministers and religious leaders tweet? They have a similar responsibility to Tweet with the freedom of their followers in mind — with respect, with accuracy and truthfulness. It becomes a moral responsibility to do this well. Currently many leaders are not leading by example, and trust in social media content has dropped as a result.

Sputnik: Can we say that it's not viable for authorities to have this alternative media platform, which gathers the entire spectrum of views not covered by the mainstream media?

Paul Levy: This technology is evolving. We could ask if the current free model of social media led by corporations is the right one to ensure free access to shared information. While it is based on advertising revenue, there is a conflict of interest at the heart of it. Attempts are, and will be made to resolve this through regulation. But could social media also be enabled through more independent holders of these platforms, such as news agencies claim to be? What would be the alternative to social media facilitated by neither big companies NOR regulating governments? Could AI enable a fairer, more neutral governance? These questions currently have no clear answers.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the speaker and do not necessarily reflect Sputnik's position.