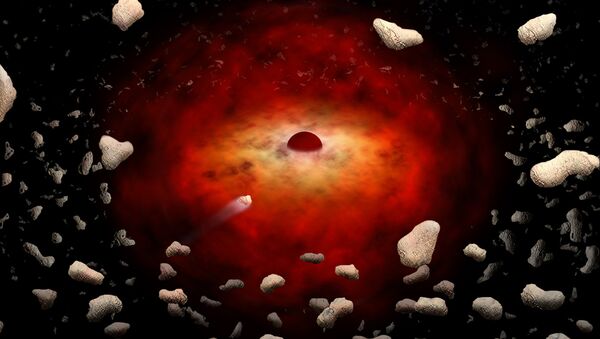

Last October, shortly before the first image of the supermassive black hole of galaxy M87 saw the light of day, thanks to the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), astronomers announced a no less stunning detail – that they had found some possibly plasma-made “hotspots” spinning around the innermost possible orbit of a supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A (Sgr A), at the Milky Way’s centre.

Compared to other black holes, Sagittarius A is bleaker and less striking in appearance despite its enormous mass being approximately four million times greater than the mass of our sun. However, the data from the EHT has shed some light on the way material flows towards black holes, growing into what the Perimeter Institute’s Avery Broderick called “monsters lurking in the night”.

Meanwhile, as for astrophysicists, this glimpse of the plasma blobs is important in and of itself, with researchers saying that they have witnessed “a totally new environment, which is totally unknown”, according to a cosmologist from Munich, Nico Hamaus, quoted by the Daily Galaxy.

The newly detected hotspots, per researcher Joshua Sokol, “afford astronomers their closest look yet at the funhouse-mirrored space-time that surrounds a black hole”.

“And in time, additional observations will indicate whether those known laws of physics truly describe what’s going on at the edge of where space-time breaks down”, he noted, while Oliver Pfuhl, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, dubbed it a “mind-boggling” experience to actually “witness material orbiting a massive black hole at 30 percent of the speed of light”.

The material emission from highly energetic electrons that are very close to the black hole became visible as three outstanding bright flares, essentially matching forecasts about hot spots orbiting gigantic black holes. The flares are thought to originate from magnetic interactions in the hot gas blobs.

To effectively examine the curious flares, researchers made use of the ESO’s (European Southern Observatory) exceptionally sensitive GRAVITY instrument on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) Interferometer, with light from the four telescopes at the VLT array in Cerro Paranal, Chile, being combined to arrive at one singularly giant telescope.

Earlier this year, GRAVITY, coupled with another VLT instrument, SINFONI, enabled the same research team to accurately estimate the close fly-by of the star S2 as it whizzed through the extreme gravitational field near Sagittarius A, thereby revealing the effects predicted by Albert Einstein in his general relativity theory in an extreme environment, as during the fly-by a strong infrared emission was registered.