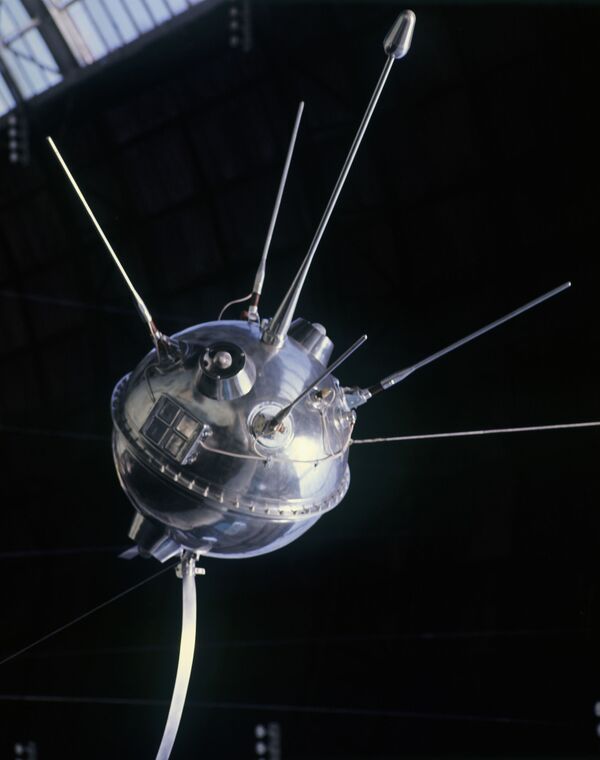

The era of lunar exploration with the use of space technology began on 2 January, 1959, when the Soviet Union launched the Luna-1 automatic interplanetary station, the first spacecraft sent toward the Moon.

Getting close to the Moon on 4 January, the station passed within 6,000 kilometres (3,728 miles) from it and became the first spacecraft to enter orbit around the Sun. The data on the radiation environment and the gas components of interplanetary matter in the near-Moon space was obtained with the help of the Luna-1 scientific equipment. The Luna-1 was also used to determine the absence of a significant magnetic field near the Moon and the radiation belts around it.

The next spacecraft, Luna-2, was launched on September 12, 1959. After successfully completing its research, it intentionally crashed into the Moon on 14 September, 1959 at a speed of 3.3 kilometres (2 miles) per second. It became the first space flight, carried out from the Earth to another celestial object. Studies conducted by the Luna-2 confirmed the data that the Moon does not have a noticeable magnetic field, that there are no radiation belts around it.

On 4 October, 1959, the Luna-3 automatic interplanetary station was launched. It flew around the Moon and photographed its far side. Pictures, taken at a distance of 60,000-70,000 kilometres from the lunar surface and transmitted via radio to Earth, provided the first idea about this side of the Moon.

The Moon exploration was subsequently continued with the help of the Soviet automatic stations of the Zond and Luna series, as well as US stations of the Pioneer and Ranger series. The obtained scientific information allowed Soviet scientists to make the first complete map and the first globe of the Moon.

A new stage of the Moon study began on 3 February, 1966, when the Luna-9 station, launched on 31 January, made the first soft landing on the surface of the Moon in the Ocean of Storms area. It became the first soft landing mission on the Moon and the first spacecraft on the surface of another celestial body, with which radio communications sessions were conducted.

The Luna-9 transmitted to Earth the world’s first circular photo-panorama of the lunar surface in the landing area of the station, and also made measurements of the intensity of radiation. It spent 75 hours on the lunar surface.

The studies were continued by the Luna-13 automatic station, which was launched on 21 December, 1966. It made a soft landing on December 24 near the western edge of the Ocean of Storms, some 400 kilometres from the landing site of the Luna-9 station.

Studies of physical and mechanical properties of the lunar soil were conducted with the help of the Luna-13 equipment. In addition, the heat flow and corpuscular radiation near the lunar surface were measured. Eight photo and television communication sessions were conducted with the Luna-13 in three days. It also transmitted three panoramas of the lunar surface.

The Luna-10 station was launched on 31 March, 1966. On 3 April, it entered orbit around the Moon and became its first artificial satellite. Studies of the Moon and near-Moon space were conducted with the help of its equipment. Data on general chemical status of the Moon were obtained for the first time.

Communication with the station was maintained until 30 May. During the 56 days of its active existence, the Luna-10 went 460 times around the Moon and made 219 radio communication sessions.

Studies of the Moon were continued by the Soviet stations of the Luna series, bearing numbers of 11, 12, 14, and 15. They made it possible to obtain detailed images of large areas of the Moon sides to determine the anomalies of its gravitational field and to study the meteoroid and radiation environment around it.

From 1966 to 1968, the United States put five Lunar Orbiter stations and one Explorer station into orbit around the Moon. At the same time, sending seven Surveyor spacecraft to land on the Moon.

The last three spacecraft of this series — Surveyor 5, 6, and 7 — had a device for determining the content of a number of chemical elements in the soil substance of the Moon’s surface. This was the beginning of the chemical composition’s measurement of the lunar soil directly on the Moon surface.

Soviet automatic stations Zond-5 (September 1968) and Zond-6 (November 1968) had successfully returned scientific laboratories from space to Earth. These devices circled the Moon and returned safely to Earth, completing all the planned scientific experiments.

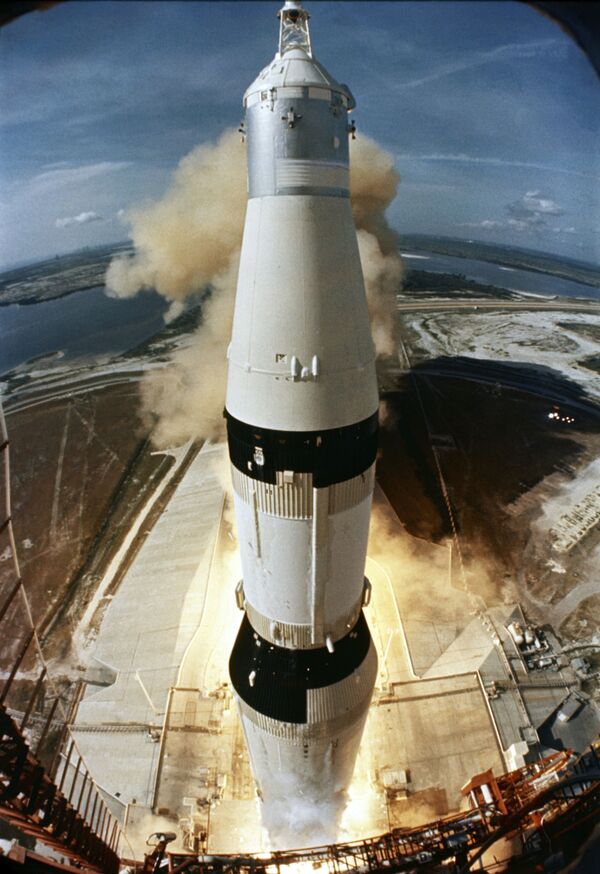

Human spaceflights under the US Apollo programme played an important role in the study of the Moon. The US Apollo 8 spacecraft with three astronauts aboard was launched on 21 December, 1968. It flew 10 times around the Moon and successfully returned to Earth.

The crew of the Apollo 10 spacecraft, which lifted off in May 1969 and also circled over the Moon, worked out operations related to ensuring the landing on the Moon and the return of astronauts back to Earth.

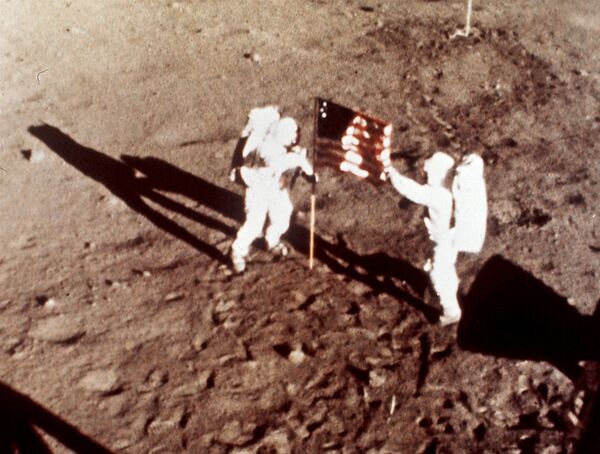

Launched on 16 July, 1969, from Cape Kennedy, a manned module of the Apollo 11 spacecraft landed on the Moon with two US astronauts on July 20. Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk on the Moon. Buzz Aldrin became the second one. Astronauts took photographs of the lunar surface and collected lunar samples. They returned to Earth on July 24.

Another 10 people visited the Moon during the subsequent launches of the Apollo spacecraft. Astronauts delivered several hundred kilograms of samples to Earth and carried out a series of studies on the Moon: they measured heat flow, magnetic field, radiation level, intensity and composition of the solar wind.

At the same time, studies of the Moon were conducted by the Soviet Luna automatic interplanetary station. On 24 September, 1970, Luna-16 station made the first automatic delivery of lunar substance to Earth. A draghead, which was used for the first time, drilled the lunar surface to a depth of 35 centimetres (13.7 inches), collected the soil and transported samples to the container at the station.

The Luna-17 was launched on 10 November, 1970. It delivered to the Moon the Lunokhod-1 unmanned lunar rover, which travelled 10.5 kilometres for 10.5 months and transmitted a large number of panoramas, individual photographs of the Moon’s surface and other scientific information to Earth. It had a French reflector, which made it possible to measure the distance to the Moon with a laser beam. The last communication session with the Lunokhod-1 was on September 14, 1971, after which the Moon Night fell, and on September 30 the contact with the machine was lost.

In February 1972, the Luna-20 station delivered samples of lunar soil, which for the first time were taken from a hardly accessible area of the Moon, to Earth. In January 1973, Luna-21 delivered Lunokhod-2 to the Moon. From January to May 1973, Lunokhod-2 travelled a distance of about 37 kilometres, transmitted 93 telephotometric panoramas and about 89,000 slow-scan television pictures. Stereoscopic images of the most interesting peculiarities of the landscape were also obtained. The work of Lunokhod-2 was shut down due to overheating. The telemetric information was last received from Lunokhod-2 on 10 May, 1973.

Hiatus in Moon Exploration

In December 1972, the US lunar program ended with the Apollo 17 sixth landing on the Moon, and the Luna-24 station was launched in August 1976, becoming the last Soviet Union spacecraft launched to the Moon.

The Moon exploration programs were shut down in the Soviet Union and the United States almost simultaneously in the mid-1970s. It was very expensive to fly to the Moon.

Since that time the Moon exploration had stopped. Only Japan sent its Hiten artificial satellite to the Moon in 1990. Then two US spacecraft Clementine (1994) and Lunar Prospector (1998-1999), as well as SMART-1 spacecraft of the European Space Agency conducted remote probing of the Moon from the lunar orbit.

Thanks to SMART-1 spacecraft, the scientists "for the first time managed to detect the presence of calcium and magnesium" on the Moon, and also made "mapping surveys of the lunar surface, including its dark side."

Moon Exploration in 21st Century

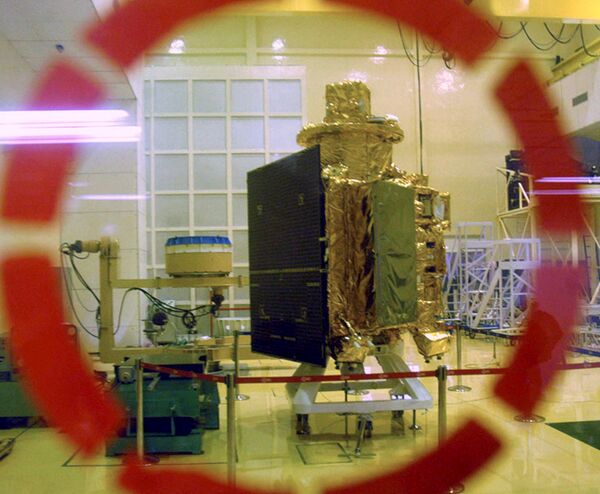

At the beginning of the 21st century, China and India joined the lunar research using artificial Moon satellites. The first Chinese lunar satellite, Chang’e, was launched in October 2007. It worked in the lunar orbit for 16 months and successfully landed on the Moon in March 2009. It collected the data, which allowed Chinese scientists to create, in particular, the first heat map of the Moon.

The first Indian Chandrayaan 1 lunar probe was launched in October 2008. The spacecraft worked in the Moon’s orbit for 312 days until August 29, 2009, making 3,400 flights over the Moon and transmitting thousands of surface photographs and chemical data to Earth.

At the end of June 2009, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) were launched into space on the US Atlas 5 carrier rocket, equipped with Russian third-stage engines. They confirmed that ice was present in lunar pole craters.

On October 1, 2010, China launched the Chang’e-2 lunar satellite, one of the basic aims of which was to gather the necessary information for the successful landing of spacecraft on the Moon surface. After completing the transmission of high-resolution images of the lunar surface, Chang’e-2 flew by the asteroid named Toutatis and took pictures of it.

In September 2013, the US Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE) spacecraft was launched into space. It reached the low lunar orbit from 12 to 60 kilometres above the satellite’s surface and began to study the rarefied atmosphere of the Moon. LADEE worked for 128 days and made its planned crash into the lunar surface on 18 April, 2014.

In 2013, Chinese Chang’e-3 delivered the Yutu rover to the Moon. It carried out a study of the lunar surface for 31 months, exceeding the estimated period of work by 19 months. The rover was able to complete a large number of complex missions and take pictures of the geological layers of the Moon for the first time. It stopped its work on August 3, 2016.

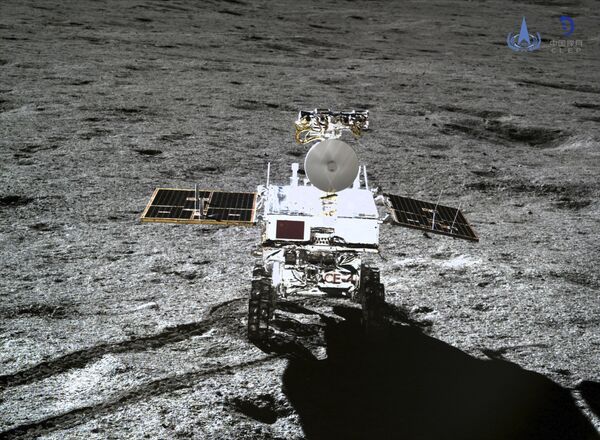

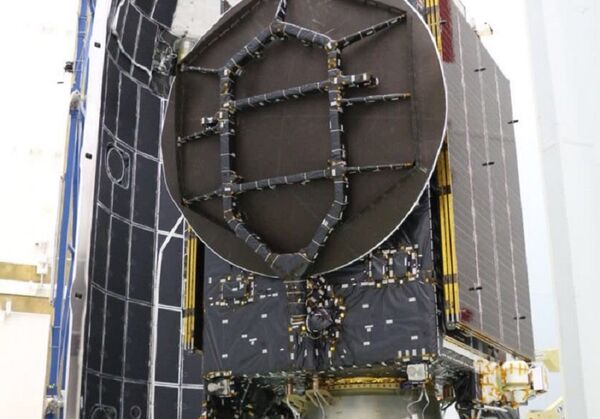

In 2019, China launched the next phase of its lunar program: the first-ever landing on the far side of the Moon. In order to do this, China launched the Queqiao relay satellite for the Chang’e-4 lunar mission in May 2018. In June, it successfully entered its Earth-Moon L2 halo orbit and became the first satellite in the world to operate in it.

The Chang’e-4 lunar rover, launched on 7 December, 2018, landed on the Von Karman Crater located in the southern hemisphere on the far side of the Moon on January 3, 2019. The "Yuuta-2" rover discovered two types of lunar mantle material on the far side of the Moon. Further measurements and experiments that Chinese scientists plan to conduct with the help of the lunar rover will help verify other theories describing the formation of the Moon and understand which of them is closest to reality.

The Chinese lunar program includes delivery of lunar soil by Chang’e-5 and Chang’e-6. After that, it is planned to begin preparations for a manned flight to the Moon to construct the first lunar base. Chang’e-7 suggests a general study of the Moon’s south pole, including terrain and landforms, while Chang’e-8 is expected to test key technologies on the lunar surface. In April 2019, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) head, Zhang Kejian, announced that China plans to build research station on the lunar south pole and carry out a lunar manned mission within the next 10 years.

The first Israeli Beresheet spacecraft, which was launched at the end of February 2019, reached Earth satellite orbit and crashed at the final stage of the mission in mid-April due to engine failure during landing. Beresheet went into the lunar orbit in early April, making Israel the seventh country in the world that managed to do this. The country plans to build a new spacecraft, Beresheet-2, which will try to complete the task of its predecessor.

India plans to send the Chandrayaan-2 automatic station to the Moon in July 2019. It will land on the Moon and deliver a small rover to its surface.

Moon Exploration Efforts By United States

The US leadership was unable to determine the future purpose of the lunar program. In 2003, President George W. Bush "resumed" the lunar program. It included flights to the Moon and creation of a permanent base there with the prospect of a flight to Mars. In 2011, President Barack Obama shut the program down. In December 2017, US President Donald Trump signed a decree to reinstate the lunar program.

As part of the new lunar program, NASA has a human lunar lander concept that can take people to and from the lunar surface. The draft presidential budget for NASA for 2020 stipulated that the United States planned to land astronauts on the Moon by 2028, but in March 2019, Trump ordered to put US astronauts back on the moon within five years "by any means necessary." As a result, NASA and the White House once again changed their plans, dividing the US lunar program, called Artemis, into two halves. The first one includes Washington’s plans to build not the entire lunar station, but to send only one of its modules to the lunar orbit, and use it as a kind of "transit point" for manned expeditions to the surface of the Earth’s satellite. The second one includes plans to expand the orbital base and prepare the first flights to Mars. The station’s construction program is scheduled to begin in 2022.

Russia-US Lunar Exploration Initiatives

In September 2017, NASA and Russia’s state space corporation Roscosmos signed an agreement on the possibility of the creation of a lunar orbital station called Deep Space Gateway in the 2020s. But subsequent negotiations between Moscow and Washington were soured, as the Russian side was not satisfied with its role in this project.

Roscosmos head Dmitry Rogozin said that Russia would not participate in the creation of the station "as a member of juries" and be limited to the creation of a single module. Some of these problems were resolved in October 2018, but the United States did not abandon its intention to create a near-moon station as an "American," rather than an "international project." According to Rogozin, when the United States figures out a way to rationalise the Gateway program, then there will be the groundwork for discussions.

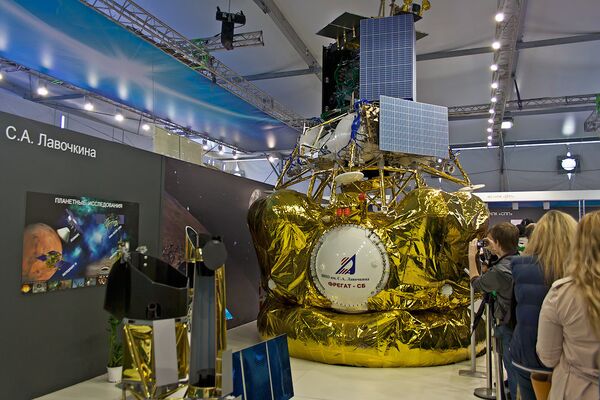

Russia also has a lunar program, which includes sending several orbiting vehicles and lunar module descent engines to the Moon, creating a long-term base on its surface and studying the Moon using robotic avatars. The first landing of the Russian cosmonaut on the Moon is scheduled for 2030, while the launch of the Luna-25 spacecraft to test technologies for soft landing is planned for 2021. The Luna-26 spacecraft will fly to the Moon in 2024 in order to map and remotely study the surface of the Earth’s satellite. In 2025, the Luna-27 spacecraft will be sent to the Moon to take soil samples at the Moon’s south pole and study them.

According to Rogozin, the flight around the Earth’s satellite is scheduled to take place in 2029, and after 2030 Russia plans to deploy bases for the life and work of cosmonauts on the Moon.