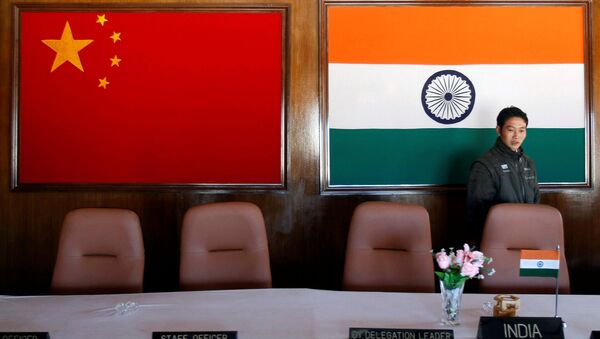

Both leaders are scheduled to meet in the southern Indian resort town of Mamallapuram on 11 and 12 October for informal discussions on a wide range of issues of mutual interest.

India’s recent move to revoke the quasi-autonomous status of Jammu and Kashmir State irked China but “both New Delhi and Beijing are aware that a rapidly changing world order is beckoning them to set their differences aside and “learn to co-exist in a common neighbourhood,” observes Zorawar Daulet Singh, a Fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, a New Delhi-based Indian think tank.

The 2017 stand-off between Indian and Chinese troops over China constructing a road in Doklam area near the tri-junction border area claimed by it and India's ally Bhutan was a possible tipping point in relations between the two states. After that, both New Delhi and Beijing decided to reassess and rework their relationship in each other’s national interest, Singh says in an article for the Indian daily The Hindu on Thursday.

“It was only with the outbreak of the border crisis and the possibility of a conflict that both leaderships undertook a sober assessment of the complex historical forces at play,” he writes.

He cites three historical factors as shaping the India-China relationship over the last decade first, a changing world order and the rise of Asia. Second, the idea that with the West’s declining capacity and inclination to responsibly manage international and Asian affairs, India, China and other re-emerging powers are being thrust into new order building roles. Third, a changing South Asia with China’s 2013 and 2014 policy declarations of deepening ties with its periphery, including sub-continental states, followed soon after with the ambitious Belt and Road initiative and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor in April 2015.

“Over the past decade, three historical forces have been shaping India-China relations. Some of these forces have been pushing both countries towards competition and some impelling them towards cooperation and collaboration,” Singh states.

Prime Minister Modi and President Xi’s first informal summit meeting at Wuhan in April 2018 went a long way towards stabilising bilateral ties at a time when major global changes were taking place, and that “basic understanding must continue,” the Centre for Policy Research analyst states.

“In retrospect, the Doklam episode in the high Himalayas was really the culmination of a deeper festering question — how would India and China relate to each other as their footprints grew in their overlapping peripheries? This, in essence, was the backdrop to the April 2018 'informal summit' in Wuhan, where both sides decided to arrest the deterioration in the relationship and attempt to chart a fresh course,” Singh added.

Post-Wuhan, he states, both New Delhi and Beijing have accepted that as two major powers with independent foreign policies, both recognise the “importance of respecting each other’s sensitivities, concerns and aspirations” and need to “strive for greater consultation on all matters of common interest, which includes building a real developmental partnership.”

Going forward, Singh concludes that the policies of India and China must be guided by three strategic goals – an inclusive security architecture in Asia that facilitates a non-violent transition to multi-polarity without disrupting economic interdependence: a fair and rules-based open international order to better reflect Indian and developing economy interests; and finally the maintenance of geopolitical peace and sustainable economic development.