The winners of the fifty-sixth competition were announced on 15 October, with the Chinese photographer Yongqing Bao receiving the title of Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2019 for his picture dubbed ''The moment''. As it is written on the competition's official Facebook page, Yongqing was selected by the judges from over 48,000 entries for his picture ''frames nature’s ultimate challenge - its battle for survival''.

Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition is run and owned by the Natural History Museum in London.

Enjoy other winners' images captivating the beauty of the natural world in our gallery.

It was early spring on the alpine meadowland of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, in China’s Qilian Mountains National Nature Reserve, and very cold. The marmot was hungry. It was still in its winter coat and not long out of its six-month, winter hibernation, spent deep underground with the rest of its colony of 30 or so. It had spotted the fox an hour earlier, and sounded the alarm to warn its companions to get back underground. But the fox itself hadn’t reacted, and was still in the same position. So the marmot had ventured out of its burrow again to search for plants to graze on. The fox continued to lie still. Then suddenly she rushed forward. And with lightning reactions,Yongqing seized his shot.His fast exposure froze the attack. The intensity of life and death was written on their faces –the predator mid-move, her long canines revealed, and the terrified prey, fore paw outstretched, with long claws adapted for digging, not fighting.Such predator-prey interaction is part of the natural ecology of the plateau ecosystem, where rodents, in particular the plateaupikas (smaller than marmots), are keystone species. Not only are they the main prey for foxes and nearly all the other predators, they are key to the health of the grassland, digging burrows that also provide homes for many small animals including birds, lizards and insects, and creating microhabitats that increase the diversity of plant species and therefore the richness of the meadows.

A small herd of malechiruleaves a trail of footprints on a snow-veiled slope in the Kumukuli Desert of China’s AltunShan National Nature Reserve. These nimble antelopes –the males with long, slender, black horns –are high-altitude specialists, found only on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. To survive at elevations of up to 5,500 metres (18,000 feet), where temperatures fall to -40 ̊C (-40 ̊F), they have unique underfur –shahtoosh (Persian for ‘king of wools’) –very light, very warm and the main reason for the species’ drastic decline. A millionchiruonce ranged across this vast plateau, but commercial hunting in the 1980s and 1990s left only about 70,000 individuals. Rigorous protection has seen a small increase, but demand –mainly from the West –for shahtooshshawls still exists. It takes three to five hides to make a single shawl (the wool cannot be collected from wild antelopes, so they have to be killed). In winter, man ychirumigrate to the relative warmth of the remote Kumukuli Desert. For years,Shangzhenhas made the arduous, high-altitude journey to record them. On this day the air was fresh and clear after heavy snow. Shadowsflowed from the undulating slopes around a warm island of sand that the chiruwere heading for, leaving braided footprints in their wake. From his vantagepoint a kilometre away (more than half a mile),Shangzhendrew the contrasting elements together before they vanished into the warmth of sun and sand.

It may look like an ant, but then count its legs –and note those palps either side of the folded fangs. Ripan was photographing a red weaver ant colony in the subtropical forest of India’s Buxa Tiger Reserve, in West Bengal, when he spotted the odd-looking ant. On a close look, he realized it was a tiny ant-mimicking crab spider, just 5 millimetres (1/5 inch)long. Many spider species imitate ants in appearance and behaviour –even smell.Infiltrating an ant colony can help a spider wanting to eat ants or to avoid being eaten by them or by predators that dislike ants. This particular spider seemed to be hunting. By reverse-mounting his lens, Ripan converted it to a macro, capable of taking extreme close-ups. But with the electrical connection lost between the lens and camera,settings had to be adjusted manually, and focusing was tricky, as the viewfinder became dark while he narrowed the aperture to maximize the depth of field. Here, the lens was so close that the diminutive arachnid seems to have been able to see its reflection and is raising its legs as a warning.

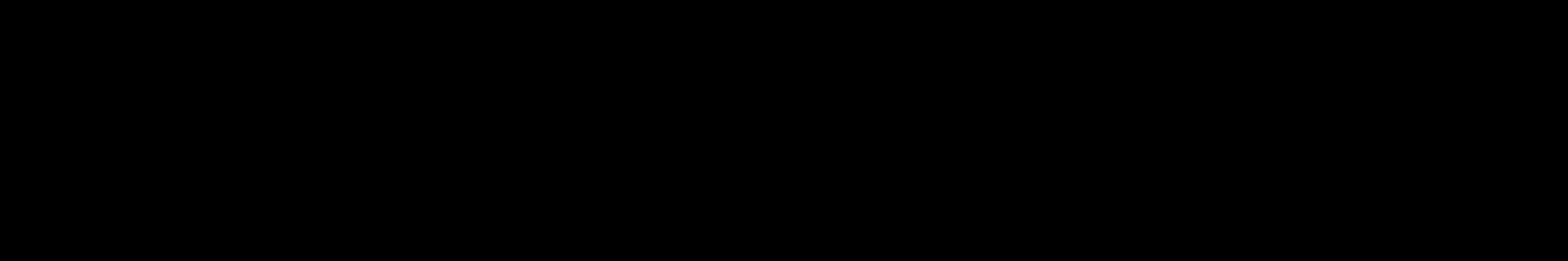

The colony of garden eels was one of the largest David had ever seen, at least two thirds the size of a football field, stretching down a steep sandy slope off Dauin, in the Philippines –a cornerstone of the famous Coral Triangle. He rolled off the boat in the shallows and descended along the colony edge, deciding where to setup his kit.He had long awaited this chance, sketching out an ideal portrait of the colony back in his studio and designing an underwater remote system to realize his ambition.It was also a return to a much-loved subject –his first story of very many stories in National Geographic was also on garden eels. These warm-water relatives of conger eels are extremely shy, vanishing into their sandy burrows the moment they sense anything unfamiliar.David placed his camera housing (mounted on a base plate, with a ball head) just within the colony and hid behind the remnants of a shipwreck. From there he could trigger the system remotely via a 12-metre (40-foot) extension cord. It was several hours before the eels dared to rise again to feed on the plankton that drifted by in the current. He gradually perfected the set-up, each time leaving an object where the camera had been so as not to surprise the eels when it reappeared. Several day slater –now familiar with the eels’ rhythms and the path of the light –he began to get images he liked.When a small wrasse led a slender cornet fish through the gently swaying forms, he had his shot.

More than 5,000 male emperor penguins huddle against the wind and late winter cold on the sea ice of Antarctica’s Atka Bay, in front of the Ekström Ice Shelf. It was a calm day, but when Stefan took off his glove to delicately focus the tilt-shift lens, the cold ‘felt like needles in my fingertips’. Each paired male bears a precious cargo on his feet–a single egg –tucked under a fold of skin (the brood pouch) as he faces the harshest winter on Earth, with temperatures that fall below -40 ̊C (-40 ̊F), severe wind chill and intense blizzards. The females entrust their eggs to their mates to incubate and then head for the sea, where they feed for up to three months. Physical adaptations–including body fat and several layers of scale-like feathers, ruffled only in the strongest of winds–help the males endure the cold, but survival depends on cooperation. The birds snuggle together, backs to the wind and heads down, sharing their body heat. Those on the windward edge peel off and shuffle down the flanks of the huddle to reach the more sheltered side, creating a constant procession through the warm centre, with the whole huddle gradually shifting downwind. The centre can become so cosy that the huddle temporarily breaks up to cool off, releasing clouds of steam. From mid‑May until mid-July, the sun does not rise above the horizon, but at the end of winter, when this picture was taken, there are a few hours of twilight. That light combined with modern camera technology and a longish exposure enabled Stefan to create such a bright picture.

Festooned with bulging orange velvet, trimmed with grey lace, the arms of a Monterey cypress treeweave an otherworldly canopy over Pinnacle Point,in Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, California, USA.This tiny, protected coastal zone is the only place in the world where natural conditions combine to conjure this magical scene. Though the Monterey cypress is widely planted (valued for its resistance to wind, salt, drought and pests), it is native only on the Californian coast in just two groves. Its spongy orange cladding is in fact a mass of green algae spectacularly coloured by carotenoid pigments, which depend on the tree for physical support but photosynthesize their own food. The algal species occurs widely, but it is found on Monterey cypress trees only at Point Lobos, which has the conditions it needs –clean air and moisture, delivered by sea breezes and fog. The vibrant orange is set off by the tangles of grey lace lichen (a combination of alga and fungus), also harmless to the trees.After several days experimenting,Zorica decided on a close-up abstract of one particular tree.With reserve visitors to this popular spot confined to marked trails, she was lucky to get overcast weather (avoiding harsh light) at a quiet moment. She had just enough time tofocus-stack 22 images (merging the sharp parts of all the photos) to reveal the colourful maze in depth.

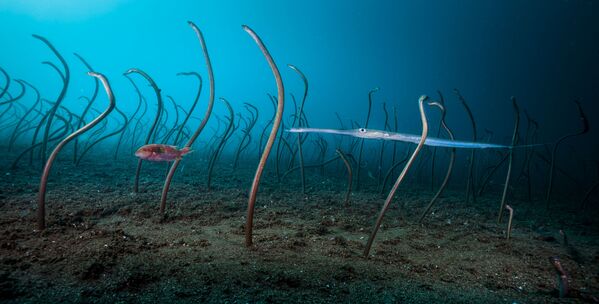

Cruz was on an organized night dive in the Lembeh Strait off North Sulawesi, Indonesia and, as an eager photographer and speedy swimmer, had been asked to hold back from the main group to allow slower swimmers a chance of photography. This was how he found himself over an unpromising sand flat, in just 3metres (10 feet) of water. It was here that he encountered the pair of bigfin reef squid. They were engaged in courtship, involving a glowing, fast‑changing communication of lines, spots and stripes of varying shades and colours. One immediately jetted away, but the other –probably the male –hovered just long enough for Cruz to capture one instant of its glowing underwater show.

For the past 17 years Riku, a Japanese macaque legally captured from thewild, has performed comedy skits three times a day in front of large audiences at the Nikkō Saru Gundan theatre north of Tokyo. These highly popular shows, which attract both locals and tourists, derive from Sarumawashi (translated as ‘monkey dancing’) –a traditional Japanese performance art that has been around for more than 1,000 years. The appeal of these contemporary performances lies in the anthropomorphic appearance of the trained macaques–invariably dressed in costumes –that move around the stage on two legs performing tricks and engaging in ridiculous role-plays with their human trainers. Photography is banned at shows, and so it took a long time for Jasper to gain permission to take pictures. Recording Riku’s performance on stage –here with one of the trainers dressed in a Scottish kilt –he was appalled that such intelligent animals, once considered sacred, are now exploited for laughs. Riku was finally retired in 2018.

On holiday with his family in France, Thomas was eating supper in the garden on a warm summer’s evening when he heard the humming. The sound was coming from the fast-beating wings of a hummingbird hawkmoth, hovering in front of an autumn sage, siphoning up nectar with its long proboscis.Its wings are reputed to beat faster than the hummingbirds that pollinate the plant in its native home of Mexico and Texas. With the moth moving quickly from flower to flower it was a challenge to frame a picture. But Thomas managed it, while capturing the stillness of the moth’s head against the blur of its wings.

Riccardo could not believe his luck when, at first light, this female gelada, with a week-old infant clinging to her belly, climbed over the cliff edge close to where he was perched. He was with his father and a friend on the high plateau in Ethiopia’s Simien Mountains National Park, there to watch geladas –a grass-eating primate found only on the Ethiopian Plateau. At night, the geladas would take refuge on the steep cliff faces, huddling together on sleeping ledges,emerging at dawn to graze on the alpine grassland. On this day, a couple of hours before sunrise, Riccardo’s guide again led them to a cliff edge where the geladas were likely to emerge, giving him time to get into position before the geladas woke up. He was in luck. After an hour’s wait,just before dawn, a group started to emerge not too far along the cliff. Moving position while keeping a respectful distance –and away from the edge –Riccardo was rewarded by this female, who climbed up almost in front of him. Shooting with a low flash to highlight her rich brown fur against the still-dark mountain range,he caught not only her sideways glance but also the eyes of her inquisitive infant.

Red-hot lava tongues flow into the Pacific Ocean, producing huge plumes of noxious laze –a mix of acid steam and fine glass particles –as they meet the crashing waves. This was the front line of the biggest eruption for 200 years of one of the world’s most active volcanos –Kîlauea,on Hawaii’s Big Island.[Field][Field][Field]Kîlauea started spewing out lava through 24 fissures on its lower East Rift at the start of May 2018.In a matter of days, travelling at speed, the lava had reached the Pacific on the island’s southeast coast and begun the creation of a huge delta of new land. It would continue flowing for three months. By the time Luis could hire a helicopter with permission to fly over the area, the new land extended more than 1.6 kilometres (a mile) from shore. Luis had limited time to work, with the helicopter forbidden to descend more than 1,000 metres (3,280 feet) and with the noxious clouds of acid vapour filling the sky. He had chosen to fly in late afternoon, so the side light would reveal the relief and cloud texture. Thick clouds of laze covered the coast, but as dusk fell, there was a sudden change in wind direction and the acidic clouds moved aside to reveal a glimpse of the lava lagoons and rivers. Framing his shot through the helicopter’s open door, Luis captured the collision boundary between molten rock and water and the emergence of new land.

On Pearl Street, in New York’s Lower Manhattan, brown rats scamper between their home under a tree grille and a pile of garbage bags full of food waste. Their ancestors hailed from the Asian steppes, travelling with traders to Europe and later crossing the Atlantic. Today, urban rat populations are rising fast. The rodents are well suited for city living –powerful swimmers, burrowers and jumpers, with great balance, aided by their maligned long tails. They are smart –capable of navigating complex networks such as sewers. They are also social and may even show empathy towards one another. But it’s their propensity to spread disease that inspires fear and disgust. Attempts to control them, though,are largely ineffective. Routine poisoning has led to the rise of resistant rats.Burrows have been injected with dry ice (to avoid poisoning the raptors that prey on them), and dogs have been trained as rat killers. The survivors simply breed(prolifically) to refill the burrows and gorge nightly on any edible trash left around.Lighting his shot to blend with the glow of the street lights and operating his kit remotely, Charlie realized this intimate street-level view.

At dusk, Daniel tracked the colony of nomadic army ants as it moved, travelling up to 400 metres (a quarter of a mile) through the rainforest near La Selva Biological Station, northeastern Costa Rica. While it was still dark, the ants would use their bodies to build a new daytime nest (bivouac) to house the queen and larvae.They would form a scaffold of vertical chains (see top right) by interlocking claws on their feet and then create a network of chambers and tunnels into which the larvae and queen would be moved from the last bivouac. At dawn, the colony would send out raiding parties to gather food, mostly other ant species. After 17 days on the move, the colony would then find shelter –a hollow tree trunk,for example –and stay put while the queen laid more eggs, resuming wandering after three weeks. The shape of their temporary bivouacs would depend on the surroundings –most were cone-or curtain-shaped and partly occluded by vegetation. But one night, the colony assembled in the open, against a fallen branch and two large leaves that were evenly spaced and of similar height,prompting a structure spanning 50 centimetres (20 inches) and resembling ‘a living cathedral with three naves’. Daniel very gently positioned his camera on the forest floor within centimetres of the nest, using a wide angle to take in its environment, but wary of upsetting a few hundred thousand army ants. ‘You mustn’t breathe in their direction or touch anything connected to the bivouac,’he says. The result was a perfect illustration of the concept of an insect society as a super organism.

In a winter whiteout in Yellowstone National Park, a lone American bison stands weathering the silent snow storm. Shooting from his vehicle, Max could only just make out its figure on the hillside. Bison survive in Yellowstone’s harsh winter months by feeding on grasses and sedges beneath the snow. Swinging their huge heads from side to side, using powerful neck muscles –visible as their distinctive humps –they sweep aside the snow to get to the forage below.Slowing his shutter speed to blur the snow and ‘paint a curtain of lines across the bison’s silhouette’, Max created an abstract image that combines the stillness of the animal with the movement of the snowfall. Slightly overexposing it to enhance the whiteout and converting the photograph to black and white accentuated the simplicity of the scene.

Fur flies as the puma launches her attack on the guanaco. For Ingo, the picture marked the culmination of seven months tracking wild pumas on foot, enduring extreme cold and biting winds in the Torres del Paine region of Patagonia, Chile.The female was Ingo’s main subject and was used to his presence. But to record an attack, he had to be facing both prey and puma. This required spotting a potential target –here a big male guanaco grazing apart from his herd on a small hill –and then positioning himself downwind, facing the likely direction the puma would come from. To monitor her movements when she was out of his sight, he positioned his two trackers so they could keep watch with binoculars and radio Ingo as the female approached her prey. A puma is fast –aided by a long, flexible spine (like that of the closely related cheetah) –but only over short distances. For half an hour, she crept up on the guanaco. The light was perfect, bright enough for a fast exposure but softened by thin cloud, and Ingo was in the right position. When the puma was within about 10 metres (30 feet), she sprinted and jumped. As her claws made contact, the guanaco twisted to the side,his last grassy mouthful flying in the wind. The puma then leapt on his back and tried to deliver a crushing bite to his neck. Running, he couldn’t throw her off, and it was only when he dropped his weight on her, seemingly deliberately, that she let go, just missing a kick that could easily have knocked out her teeth or broken bones. Four out of five puma hunts end like this –unsuccessfully.

16/19

© Photo : Audun Rikardsen / Wildlife Photographer of the Year

High on a ledge, on the coast near his home in northern Norway, Audun carefully positioned an old tree branch that he hoped would make a perfect golden eagle lookout. To this he bolted a tripod head with a camera, flashes and motion sensor attached, and built himself a hide a short distance away. From time to time, he left road-kill carrion nearby. Very gradually –over the next three years –a golden eagle got used to the camera and started to use the branch regularly to survey the coast below. Golden eagles need large territories, which most often are in open, mountainous areas inland. But in northern Norway, they can be found by the coast, even in the same area as sea eagles. They hunt and scavenge a variety of prey –from fish, amphibians and insects to birds and small and medium-sized mammals such as foxes and fawns. They have also been recorded as killing an adult reindeer.But livestock farmers in Norway have accused them of hunting sheep and reindeer rather than just scavenging carcasses, and there is now pressure to make it easier to kill eagles legally. Scientists, though, maintain that the eagles are a scapegoat for livestock deaths and that killing them will have little effect on farmers’ losses. For their size –the weight of a domestic cat but with wings spanning more than 2 metres (61/2 feet) –golden eagles are surprisingly fast and agile, soaring, gliding, diving and performing spectacular, undulating display flights.Audun’s painstaking work captures the eagle’s power as it comes in to land, talons outstretched, poised for a commanding view of its coastal realm.

Pushing against each other, two male Dall’s sheep in full winter-white coats stand immobile at the end of a fierce clash on a windswept snowy slope. For years, Jérémie had dreamed of photographing the pure-white North American mountain sheep against snow. Travelling to the Yukon, he rented a van and spent a month following Dall’s sheep during the rutting season, when mature males compete for mating rights. On a steep ridge, these two rams attempted to duel, but strong winds, a heavy blizzard and extreme cold (-40°) forced them into a truce. Lying in the snow, Jérémie was also battling with the brutal weather –not only were his fingers frozen, but the ferocious wind was making it difficult to hold his lens steady. So determined was he to create the photograph he had in mind that he continued firing off frames, unaware that his feet were succumbing to frostbite, which it would take months to recover from. He had just one sharp image, but that was also the vision of his dreams –the horns and key facial features of the mountain sheep etched into the white canvas, their fur blending into the snowscape.

Every spring, for more than a decade, Manuel had followed the mass migration of common frogs in South Tyrol, Italy. Rising spring temperatures stir the frogs to emerge from the sheltered spots where they spent the winter (often under rocks or wood or even buried at the bottom of ponds). They need to breed and head straight for water, usually to where they themselves were spawned. Mating involves a male grasping his partner, piggyback, until she lays eggs –up to 2,000, each in a clear jelly capsule –which he then fertilizes.Manuel needed to find the perfect pond in the right light at just the right time. Though common frogs are widespread across Europe, numbers are thought to be declining and local populations threatened, mainly by habitat degradation (from pollution and drainage) and disease, and in some countries, from hunting. In South Tyrol there are relatively few ponds where massive numbers of frogs still congregate for spawning, and activity peaks after just a few days. Manuel immersed himself in one of the larger ponds,at the edge of woodland, where several hundred frogs had gathered in clear water. He watched the spawn build up until the moment arrived for the picture he had in mind –soft natural light, lingering frogs, harmonious colours and dreamy reflections. Within a few days the frogs had gone, and the maturing eggs had risen to the surface.

Under a luminous star-studded Arizona sky, an enormous image of a male jaguar is projected onto a section of the US-Mexico border fence –symbolic, says Alejandro, of ‘the jaguars’ past and future existence in the United States’ .Today, the jaguar’s stronghold is in the Amazon, but historically, the range of this large, powerful cat included the southwestern US. Over the past century, human impact –from hunting, which was banned in 1997 when jaguars became a protected species, and habitat destruction–has resulted in the species becoming virtually extinct in the US. Today, two male jaguars are known to inhabit the borderlands of New Mexico and Arizona–probably originating from reserves in northwest Mexico. But with no recent records of a female –a hunter in Arizona shot the last verified female in 1963–any chance of a breeding population becoming re-established rests on the contentious border between the two countries remaining partially open. A penetrable border is also vitally important for many other species at risk, including Sonoran ocelots and migrants such as Sonoran pronghorns. The photograph that Alejandro projected is of a Mexican jaguar, captured with camera traps he has been setting on both sides of the border and monitoring for more than two years. The shot of the border fence was created to highlight President Trump’s plan to seal off the entire US‑Mexico frontier with an impenetrable wall and the impact it will have on the movement of wildlife, sealing the end of jaguars in the US.