This year’s Atlantic hurricane season is expected to wrap up in just two weeks, with Hurricane Barry causing $600 million in damages in Louisiana and Hurricane Dorian more than $8 billion in the Bahamas.

It is estimated that roughly 85 percent of all major Atlantic hurricanes start off over off the western coast of Africa when hot, dry air from the Sahara mixes with the cooler, wetter environment of the Gulf of Guinea, directly to the south.

These storms are so devastating they apparently caught the attention of US government and scientists. Unconfirmed reports emerged over the summer that Donald Trump had toyed with the idea of using nukes to disrupt hurricanes.

While turning a massive cyclone into a massive radioactive cyclone is definitely off the table (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has an entire web page dedicated to proving just that), the US has in the past experimented with taming hurricanes, albeit using more fail-safe methods.

Project Cirrus

Scientists have been trying to weaken hurricanes since the 1940s, when clouud seeding began. The idea was to disperse chemicals – such as salts, dry ice, liquid propane or silver iodide – into the air to facilitate the freezing of supercool clouds of water vapor into snow.

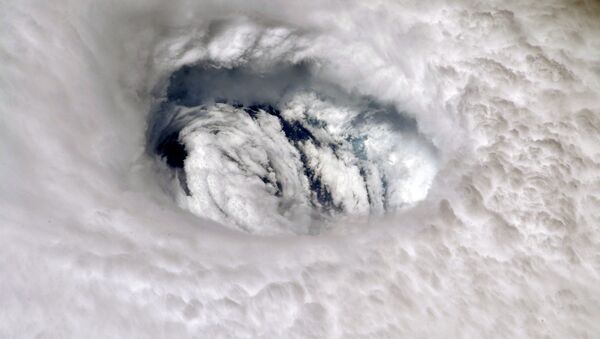

The first attempt to modify a hurricane, code-named Project Cirrus, was carried out by the General Electric and US military in October 1947. The idea was to drop dry ice into the eyewall of a hurricane so it would release enough heat to lose intensity.

After a Navy plane dropped 180 pounds of dry ice into an unnamed hurricane tracking off the coast of Florida and Georgia, it abruptly changed direction and made landfall in Georgia, causing $300 million in damages in today’s money. It wasn’t clear whether it was the seeding that affected its course, but the public’s enthusiasm for weather modification plummeted and threats of lawsuits emerged, so the project was shut down.

It wasn’t until a decade later that a scientific analysis found that the storm’s sudden change of course was due to the atmospheric winds rather than the seeding.

After the stormy years of 1954 and 1955, President Dwight Eisenhower appointed a special committee to look into storm modification.

Project Stormfury

By the early 1960s, silver iodide was found to be the most effective chemical for weather modification and was used in experiments with hurricane control. In 1961, a B-17 bomber seeded Hurricane Esther with that compound in the inaugural experiment of what would become Project Stormfury the following year.

The hurricane appeared to weaken by nearly ten percent slightly after the seeding, but later resumed strengthening. The experiment was nevertheless deemed a success and led to the 20-year stint of Project Stormfury.

The programme, launched by the US Navy and the Weather Bureau (now the National Weather Service), lasted until 1983 but oversaw similar experiments on just four hurricanes, as it lacked sufficient candidate storms. Seeding attempts in 1963 and 1969 led to a two-digit decline in the hurricanes’ sustained winds, but in both cases but were rendered inconclusive.

The last experimental flight took place in 1971, and Stormfury was deemed a failure when it ended 12 years later. Its shutdown was largely attributed to multiple new observations about the dynamics of hurricanes showing that unseeded hurricanes had similar eye-wall changes that were common in unseeded storms, casting doubt on Stormfury's basic hypothesis that chemicals are able to weaken a hurricane.

Salter Sink

Nowadays the seeding technique is forsaken, but the warming Atlantic waters are expected to provide more fuel for disastrous hurricanes in the coming years, so scientists may start engineering new ways to modify them. In fact, some already have.

Intellectual Ventures, a private-held Seattle-based company, claims it has developed a hurricane suppression method called Salter Sink. It essentially is a network of large pumps, powered by ocean waves, that pushes hot water deeper into the cooler water below. That water then cools as it returns to the surface to help weaken a hurricane.

The company says its technology has produced “some interesting early results” but further research is required for it to become reality.