In December 1995, Ukrainian President Kuchma, elected in July 1994, paid an official visit to the United Kingdom.

A brief for Prime Minister Major’s meeting with him noted that Kuchma was elected “on a platform of economic reform and closer relations with Russia”.

Kuchma’s visit to London, the brief said, provided an opportunity for Britain “to encourage him to persevere with economic and political reform”. However, closer relations with Russia sent alarm bells ringing across Whitehall.

“For domestic reasons it is important for him to demonstrate that his policy of attracting at least as much importance to developing relations with the West as to mending fences with Russia serves Ukraine’s best interests. We therefore want him to have a successful visit”.

“Really?” – Major’s private secretary scribbled on the brief.

No Alternative to NATO

British Foreign Secretary Malcolm Rifkind gave a very specific instruction to the British diplomats:

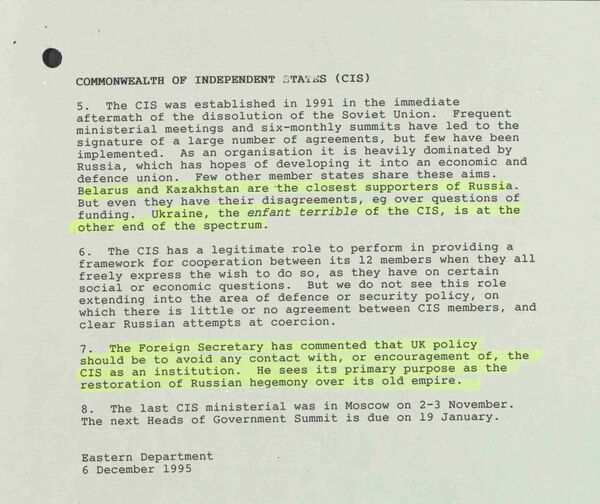

”UK policy should be to avoid any contact with, or encouragement of, the CIS as an institution. He sees its primary purpose as the restoration of Russian hegemony over its old empire”.

Among the British objectives for the UK-Ukrainian talks was “to convey to the Ukrainians that we share their skepticism about prospects for the CIS, particularly as a security organisation".

As the newly declassified British government papers show this was the leitmotif of all top level British meetings with leaders of the former Soviet republics in the mid-1990s. The British were worried that the Commonwealth of Independent States [CIS], a loose grouping comprised of most of the ex-Soviet republics, would develop into a defence alliance, along the lines of NATO. While insisting that NATO had every right to expand eastwards and that Russia had no right of veto over this expansion, the West was adamant that the CIS should not follow NATO’s example and create its own military alliance, with Russia in the lead.

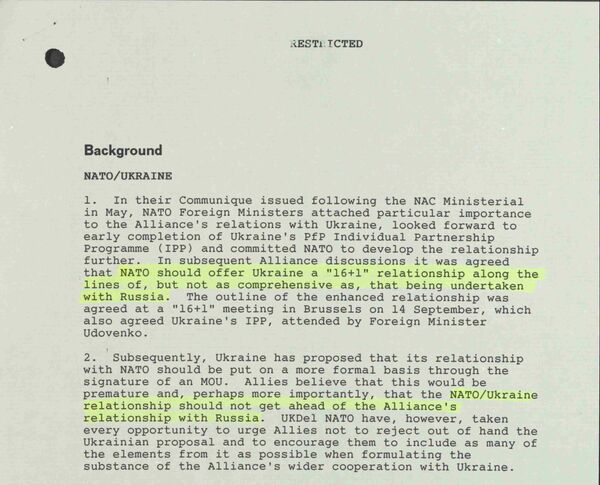

Ukraine, described as the enfant terrible of the CIS in British internal briefs, wanted its relationship with NATO to be put on a more formal basis through the signature of a Memorandum of Understanding. In Western view, the briefs said, “this would be premature and, perhaps more importantly, that the NATO-Ukraine relationship should not get ahead of the Alliance’s relationship with Russia".

UK View on NATO-Ukraine Relations. Crown Copyright the National Archives UK

Royal Diplomacy

Nor was London ready to offer Ukraine the same royal treatment it accorded to Russia.

After Queen Elizabeth II visited Russia in 1994 Ukraine was eager to get the royal seal of approval for its own nationhood. After all, Ukraine’s independence aspirations were greatly helped by the visit of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1990. The Ukrainian side kept pressing London to agree to a royal visit, if not by the Queen herself, then by somebody from the Royal Household.

The British response was very diplomatic:

“HM the Queen greatly appreciated your invitation. But She is already committed to full programme of State visits over next few years and will not be able to accept in near future".

The Ukrainians then asked for the Prince of Wales to attend commemorations of the 140th anniversary of the end of the Crimean War, to the same effect: HRH’s diary “looks full”. The Ukrainians downgraded even further to the Duke of York. Alas, that also looked “unlikely”. The intricacies of royal diaries aside, British reluctance to send august emissaries to Crimea might have been at least partly explained by Ukraine’s attitude to the thousands of British war graves on the peninsula. As the British media reported, they were neglected, dilapidated and vandalised. Kiev’s take on the issue was summed up rather bluntly: the Crimean War wasn’t Ukraine’s war.

Crimean Conundrum

But what worried the British more was “increased signs of tension between the Crimean authorities and Kiev. "If anything the economic situation in Crimea is worse than in other parts of Ukraine and the local authorities feel badly let down by the centre. Financial assistance has not been forthcoming and Kiev has concentrated almost exclusively on maintenance of security and law and order to the detriment of economic development. This is a worrying development".

No wonder, the Crimean Parliament dismissed the prime minister of the autonomous republic, Anatoly Franchuk, accusing him of being too pro-Ukrainian and attempting to profit from Crimea’s energy sector through “dubious connections” and family ties. Franchuk’s son was married to President Kuchma’s daughter and was a prominent “businessman” [as described in a British diplomatic cable – NG] in Ukraine’s energy sector. Both Franchuk and his son were deputies in the Ukrainian Parliament in Kiev, the Rada.

Franchuk was imposed on Crimea by President Kuchma in a move to stamp out the drive for reunification with Russia, after Kiev had suspended the Crimean Constitution and deposed its President Yuri Meshkov who had been elected on a reunification ticket.

British diplomats, however, cabled back home, Franchuk’s shortcomings, especially in managing Crimea’s dire economy.

“What Crimea need most is a proactive reformer at the helm. It remains to be seen whether Kuchma can find one capable of keeping Crimea’s potentially combative political forces at bay".

We now know that neither President Kuchma, nor his successors managed to find a reasonable solution to Crimea’s woes.

Best Friend in the World?

As no agreements of substance had been ready in time for the visit, the Ukrainians insisted on signing a lengthy Joint Declaration as proof of the “burgeoning” relationship. The British immediately dubbed it a “ghastly” document which no one will read.

“After the formal talks, you sign the ghastly 5-page Joint Declaration of what you have theoretically agreed in the previous half-hour. It is good Communist-style stodge, which no one in the UK will read but to which the Ukrainians, who have not yet shed all their Soviet habits, attach great importance. The ceremony will be … the usual procedure under the Churchill portrait in the lobby, with cameras. You can do all this pretty quickly, and then go up to lunch".

But the Ukrainians wanted to have the Joint Declaration signed during the photo call at the start of the formal talks, which had put the British in a quizzical mood. Wasn’t it “a bit silly” to sign something that was supposed to be first discussed at the talks, the British mused. But the Ukrainians were “attaching great importance to the presentational aspects of the occasion”. So the British relented.

Yet another bone of contention was the duration and the set-up of the talks. The British suggested 45 minutes of formal talks followed by a 75-minute working lunch in a narrow circle, restricted to the prime minister, the president and a handful of advisers. The British, as the handwritten remarks on the internal briefs show, were not keen on affording the visit too high a profile, given the uncertainty of Ukraine’s political and economic direction.

The Ukrainians appeared to be insulted by what they saw as a low key reception for their president so they asked for a written explanation as to why the time slot for the Kuchma-Major meeting at No.10 could not be extended.

To massage Ukrainian egos the British replied that a small private lunch was something that the PM would only offer to the likes of US President Clinton or German Chancellor Kohl, so Kuchma should be happy to find himself is such illustrious company.

“We have played this up with the Ukrainians as the sort of treatment that you reserve for your closest discussions with foreign leaders. Even more than usually, we want Kuchma to leave No.10 convinced of the importance we attach to the bilateral relationship”.

For fairness sake it has to be said that this tactic was not confined to Ukraine: a British brief for a visit by the then Prime Minister of Kazakhstan Akezhan Kazhegeldin said:

“By the time he leaves, you need to make Kazhegeldin feel like the UK is the Kazakh’s best friend in the world”.

The rationale for this "friendship" was spelled out in no uncertain way: “Kazakhstan has huge resources” but Britain is lagging behind the US, Germany, and France in tapping into them.

Second Class Treatment

The Ukrainians though were not lulled by the sirens’ voices and asked for a Guard of Honour for President Kuchma, to “promote the success of this important visit”. The request sent the British into a tailspin. PM’s schedule is crammed, his office replied, if he is to attend the Guard of Honour this would have to be at the expense of the time allocated for talks with Kuchma. So the Ukrainians had to decide what they wanted: 15 minutes of pomp and ceremony or 15 extra minutes of substantive talks.

The Ukrainians wanted both – and more: as the Ukrainian ambassador explained to the Foreign Office, “a very large team of ministers and officials was likely to accompany Kuchma, and would dearly love to have lunch at No. 10”. The British reluctantly offered them “the concession” of an additional seat at the “restricted” table. The ambassador also asked if Kuchma could have a doorstep appearance with the PM by the world-famous black door adorned with No.10.

John Major’s Private Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Edward Oakden wrote to his boss:

“The Ukrainians have been comparing every item in the programme for President Kuchma with what we did for his predecessor, Kravchuk, in February 1993. This is rather old-fashioned behaviour… You and Kravchuk signed a Treaty on bilateral relations between the UK and Ukraine".

“Against that background, Kuchma is desperate to sign a bit of paper with you. We don’t have any agreement conveniently to hand".

"…I thought you would be prepared at a pinch to sign a 'joint declaration'".

"This is a rather stodgy and old-fashioned document, and won’t rate more than one sentence in the British press. But it will please the Ukrainians, and be printed in their newspapers".

The Ukrainian ambassador to the UK complained that whereas previous Ukrainian President Kravchuk had been treated to a lunch with the Queen, Kuchma was only being offered 15 minutes at Buckingham Palace, and no tea!

The British took pains to reassure the Ukrainians that their president "was not being given second class treatment". But they wished to ensure that there was "substance, not just rhetoric" in UK-Ukrainian relations. To their question if the Ukrainians could offer new areas of bilateral cooperation, the Ukrainian ambassador came up with … Soviet era missiles and tanks that were still being churned out by factories in East Ukraine! The bewildered British pointed them in the direction of private defence contractors but, apparently, they were not excited by the offer.

Keeping Promises

At his meeting with PM Major on 13 December 1995, President Kuchma admitted that “Ukraine had wasted the first three years after independence” and was keen to catch up. He came to London in search of British investment and UK government guarantees for British-Ukrainian trade. He was to be disappointed as Britain could not see how Ukraine’s inability to service her foreign debt would attract foreign investors, let alone Western guarantees. By the time of the visit it had transpired that Ukraine was economical with the truth when reporting back to the IMF about its compliance with the agreed package of foreign financial aid. The IMF Directors were told that Kiev’s failure to reveal the existence of arrears meant that Ukraine was not complying with the programme even during its review. IMF staff was pessimistic about the economic outlook and spoke of a serious infringement by Ukraine of the terms of the review. Ukraine was “off-track”, the implication being that the Ukrainian authorities “were dishonest” with the IMF, a British diplomatic cable said.

The Ukrainians need to earn a reputation for meeting their bills and keeping their promises, was the British conclusion.

It looks like almost quarter of a century later there is still plenty of room for improvement…