Oscar Seborer was the child of Polish Jewish immigrants, born in New York in 1921. He studied electrical engineering at Ohio State University, was drafted in 1942, and went to work on the Manhattan Project, the US’ top secret program to develop an atomic bomb before Nazi Germany - or the Soviet Union. He witnessed the 1945 Trinity test, the first artificial nuclear detonation, proving the viability of the atom bomb.

He was also a Soviet spy by the codename “Godsend,” and for the Soviet Union’s nuclear program he was just that, feeding the communist bloc more information on how to build the advanced, highly destructive weapon than any other person.

Historians Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes have revealed the extent of Seborer’s espionage in a new paper on the spy’s life and actions. They draw on newly declassified reports from the US Central Intelligence Agency detailing the myriad secrets available to Seborer, who fled to the USSR in 1951.

“It’s fascinating,” Klehr told the New York Times. “We had no idea he was that important.”

While working at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, Klehr helped craft some of the most essential features of the first nuclear weapons, including those hardest to replicate, such as the firing circuits for their detonators, according to the documents. His insights helped the Manhattan Project engineers rapidly miniaturize the warhead, enabling it to be used in a transportable weapon dropped from an airplane and, eventually, placed on top of a missile.

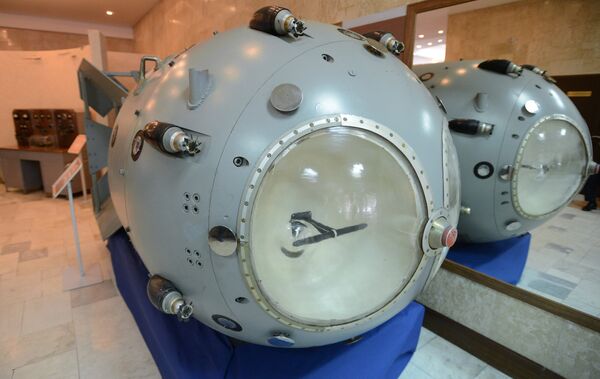

In particular, Seborer designed an “unbelievably complicated” implosion trigger that would ensure an evenly spherical compression of the warhead, which was necessary to trigger the runaway fission reaction that gives a nuclear bomb its wildly powerful explosive yield.

Alex Wellerstein, a nuclear historian at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, told the Times the Soviets “spent a lot of time looking into the detonator-circuitry issue,” noting that Seborer’s contributions “could have been unique” among all of Moscow’s spies in the program.

“I don’t know if any of the other known spies would have had access” to the kind of secrets Seborer did, he told the Times, noting Seborer and his comrades “might have filled a gap” for Soviet scientists.

For example, one Soviet diagram of a nuclear device cited by Wellerstein in a 2012 analysis dated to June 1946 - just four months after Seborer left Los Alamos - shows a firing circuit clearly inspired by the Americans’ device.

The CIA documents date to 1956, four years after Seborer settled in the Soviet Union. Klehr told the Times the FBI first uncovered evidence of Seborer’s potential espionage role in 1955, but while other Soviet spies in the program, such as Klaus Fuchs, were arrested and their discovery publicized, the politics of the 1956 election made a new spy scandal unpalatable.

However, the evidence against Seborer was also very flimsy: the documents don’t detail his espionage, they just note what he could have stolen or taught the Soviets, based on what he had access to. On top of that, he was already in the Soviet Union, so even securing an indictment was unlikely.

“It’s entirely possible - let sleeping dogs lie,” Klehr said. “But you can’t prove it.”

Klehr and Haynes’ paper notes that an FBI informant in Moscow had reported that Seborer said he and his brother Stuart, a communist who had accompanied him in exile, would be executed for “what they did” if he ever returned to the United States. In fact, in 1953, the US did execute two suspected spies, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, after they were accused of smuggling weapons designs, including from the Manhattan Project.

The Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear bomb just four years after the Trinity test, on August 29, 1949, at the Semipalatinsk test site in the Kazakh SSR.