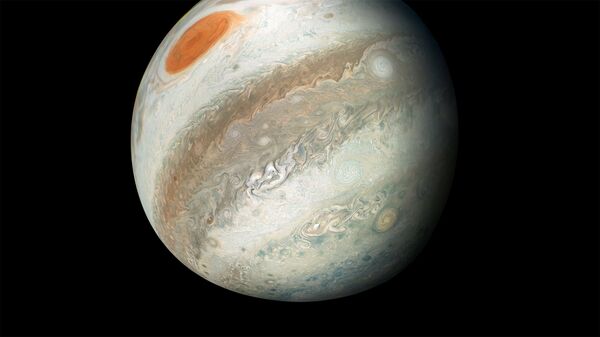

Jupiter's Great Red Spot - a gigantic storm about twice as wide as Earth – may not be shrinking as fast as previously suggested, claims a new study published on 16 March in the journal Nature Physics.

The research, “Remote determination of the shape of Jupiter’s vortices from laboratory experiments”, found that the Great Red Spot's thickness probably remained constant despite dramatic shrinkage in its area observed over a span of approximately four decades.

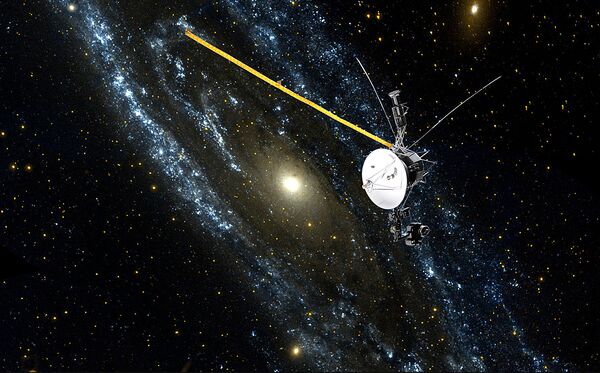

Scientists at the Institute for Research on Non-Equilibrium Processes (CNRS/Aix-Marseille Universite/Ecole Centrale de Marseille) led by Daphné Lemasquerier and her colleagues carried out numerical simulations and laboratory experiments with a salt-water-filled Plexiglas tank to study the large vortices of Jupiter, which NASA’s Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft flew by in 1979.

The new research determined the balance of forces moulding the planet’s storms and allowed the experts to offer predictions about their evolution over time.

"For the Great Red Spot in particular, our predicted horizontal dimensions agree well with measurements at the cloud level since the Voyager mission in 1979," stated the scientists.

They also suggested the Great Red Spot is about 105 miles (170 kilometres) thick, and has not undergone any substantial change since the Voyagers flew by.

The team expects the thickness predictions to be further corroborated by NASA's Juno probe, which was launched in 2011 and has been orbiting Jupiter since July 2016.

Juno, on a mission to measure Jupiter's composition, gravity field, magnetic field, and polar magnetosphere while seeking clues to how the planet formed, has the ability to penetrate the planet’s opaque atmosphere to test storm height, using a plethora of instruments.

"Our results now await comparison with upcoming Juno observations," added Lemasquerier and her colleagues in the new study.

The Great Red Spot Phenomenon

The largest planet in the solar system, Jupiter is mainly made up of liquids and gases, with its clouds shaped by vortices into parallel bands and coloured patches. The Great Red Spot is one such patch - an anticyclone that has been observed for decades. To its north, the cyclone is contained by an eastward-moving atmospheric band, and to its south - a westward-moving band.

At the storm’s centre, winds are relatively calm, but on its edges, wind speeds reach 270-425 mph (430-680 km/h).

The Great Red Spot, first observed in 1831 by amateur astronomer Samuel Heinrich Schwabe, had decreased in size in recent years, fuelling speculation that it may be dying.

In February 2018, Glenn Orton, a lead Juno mission team member and planetary scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), speculated about the giant storm's fate, reported Business Insider.

In the late 1800s, the storm might have measured as wide as 30 degrees longitude, said Orton, which is more than 35,000 miles.

However, when the Voyager 2 flew by Jupiter in 1979 the storm had shrunk to slightly over twice the width of Earth. In subsequent research in late 2019, scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, argued at a conference of the American Physical Society's Division of Fluid Dynamics that there was no evidence the vortex powering the cloud formation of the Great Red Spot on Jupiter was changing.