Antara Banerjee at the University of Colorado Boulder and her colleagues used data from satellite observations and climate change simulations to model the changing wind patterns.

According to researchers, two air current trends had been observed before the year 2000. The mid-latitude jet stream had been slowly moving towards the South Pole, and the Hadley cell - a global-scale tropical atmospheric circulation stream that causes trade winds, tropical rain-belts and hurricanes - had been widening, the New Scientist reported.

However, Banerjee’s team found that both of these trends began to reverse in 2000, partly due to the recovering ozone layer.

“Here we show that these widely reported circulation trends paused, or slightly reversed, around the year 2000. Using a pattern-based detection and attribution analysis of atmospheric zonal wind, we show that the pause in circulation trends is forced by human activities, and has not occurred owing only to internal or natural variability of the climate system,” the report states.

In addition, the study found that the “key driver” of the ozone layer recovery is the Montreal Protocol. The protocol was signed by 197 countries, including Canada, the US and China, in September 1987, and is an international treaty intended to protect the ozone layer by banning chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), chemicals used in the manufacture of aerosol sprays, propellants, refrigerants and solvents that are known to contribute to ozone depletion in the upper atmosphere.

“Signatures of the effects of the Montreal Protocol and the associated stratospheric ozone recovery might therefore manifest, or have already manifested, in other aspects of the Earth system,” the study explains.

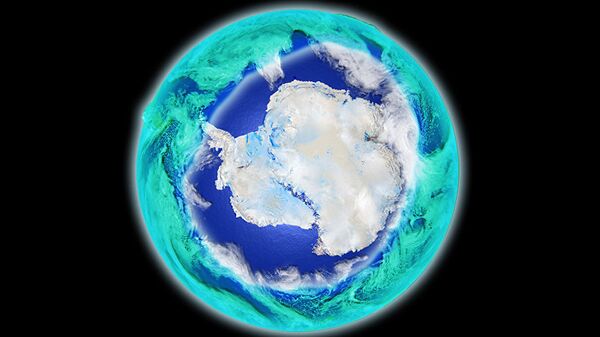

The researchers also found that the ozone layer recovers at different speeds in various parts of the atmosphere. The Antarctic ozone hole, for example, is expected to finish recovering in the 2060s.