The F-35 has a problem with its tail that limits its ability to fly faster than the speed of sound under certain conditions, unless the pilot wants to risk damaging the jet. The Pentagon’s F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO) has recently clarified that it won’t be spending time fixing the design defect, but will instead limit the jet’s missions so that it doesn’t have to do so.

“The [deficiency report] was closed under the category of ‘no plan to correct,’ which is used by the F-35 team when the operator value provided by a complete fix does not justify the estimated cost of that fix,” the JPO told Defense News in a statement on Friday.

“In this case, the solution would require a lengthy development and flight testing of a material coating that can tolerate the flight environment for unlimited time while satisfying the weight and other requirements of a control surface,” the JPO noted. “Instead, the issue is being addressed procedurally by imposing a time limit on high-speed flight.”

The problem has been observed in the B and C models of the F-35 since 2011, when the jet began experiencing “thermal damage” on its horizontal tail and tail boom, including “bubbling [and] blistering” of the stealth coating that shields the plane from enemy radars, Sputnik reported in June 2019, citing JPO documents obtained by Defense News.

However, the problem only occurred when the plane was pushed to its extremes, flying at 50,000 feet and when sprinting at full afterburner between Mach 1.3 and Mach 1.4. The solution adopted by the Department of the Navy, which uses both the vertical takeoff/landing F-35B and the carrier-based F-35C, is to simply order its pilots not to fly at such speeds.

The issue is especially problematic for the carrier-based fighters, which might not return to an airfield for months at a time, as the problem - rated as Category 1, the most serious level, by the Pentagon - is one that requires a machine shop in order to fix.

F-35 Program Executive Officer Vice Adm. Mat Winter told Defense News in June that the problem wasn’t considered serious since testers couldn’t replicate it, and engineers were getting by with a spray-on coating that provides additional heat protection.

According to Hudson Institute analyst Bryan Clark, those limitations aren’t really a big deal, because the plane rarely has to do any of those things anyway.

“Supersonic flight is not a big feature of the F-35,” Clark told Defense News. “It’s capable of it, but when you talk to F-35 pilots, they’ll say they’d fly supersonic in such limited times and cases that — while having the ability is nice because you never know when you are going to need to run away from something very fast — it’s just not a main feature for their tactics.”

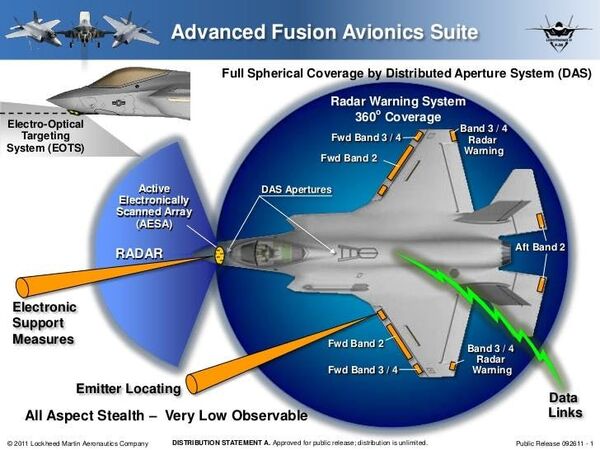

Pentagon planners have for years been reconsidering the F-35’s battlefield role, moving past the early expectations that the tiny stealth jet would accompany its larger air superiority cousins, the F-22 Raptors, into combat as ground strike aircraft. Now, it seems the Lightning II’s greatest asset, aside from its stealth, are its huge antenna suite and the wealth of information it can scoop up about enemy locations, movements and communications.

One notable example of the F-35’s capabilities was a November 2019 drill in which a US Air Force F-35A used its wide array of sensors to pinpoint a simulated enemy radar station, feeding information about its location to a US Army HIMARS rocket launcher unit, which destroyed the radar.

This is much as US Air Force Chief of Staff General David Goldfein mused in February 2019, when he told guests at the Brookings Institute think tank that the F-35 would likely function as the “quarterback” of a future air campaign, “calling audibles in real time,” Air Force Magazine reported. That future air campaign, against “near peer” rivals such as China and Russia, would likely feature F-15E Strike Eagles and F-16 Falcons as the primary attack aircraft, filling the role for which the F-35 was once envisioned.

A big part of the reason the F-35 has taken a back seat in the ground strike field is that due to another design error, its internal weapons bays can’t carry that many munitions - it was big news last May when maker Lockheed Martin announced it had found a way to fix six missiles inside the jet. The notorious “beast mode” option exists, in which the plane’s external weapons mounts are filled to the brim with munitions, but at that point, stealth is clearly no longer a concern.

However, one retired naval aviator told Defense News last June that cutting down on supersonic flight was “a pretty significant limitation.”

“If you want to use it on the first or second day [of a conflict], it has to be stealthy, so you can’t hang a lot of external stores, which means you have to use internal fuel and internal weapons,” the aviator noted. “And that means you have to launch fairly close in, and you’ve got to be close enough to do something to somebody. And that usually means you are in a contested environment.”

“So you’re saying that I can’t operate in a contested environment unless you can guarantee that I’m going to be however far away from the thing I’m trying to kill,” the aviator added. “If I had to maneuver to defeat a missile, maneuver to fight another aircraft, the plane could have issues moving. And if I turn around aggressively and get away from these guys and use the afterburner, it starts to melt or have issues.”