On May 7, 1985, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union issued a decree ‘On Measures to Overcome Drunkenness and Alcoholism’, instructing all party, administrative and law enforcement bodies to intensify the fight against drunkenness via a series of measures. These included:

- A major reduction in the production of wines, beer, and vodka, and a dramatic spike in their prices (for instance, the cost of the cheapest bottle of vodka grew from 4.70 rubles to 9.10 given an average salary of 190.1 rubles).

- A reduction in the number of stores where alcohol was available, and limiting the time when it could be sold from 2-7 pm.

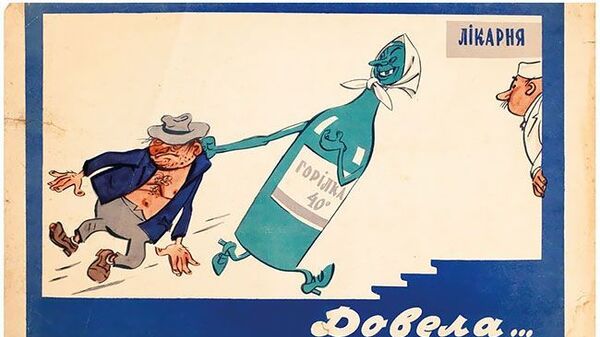

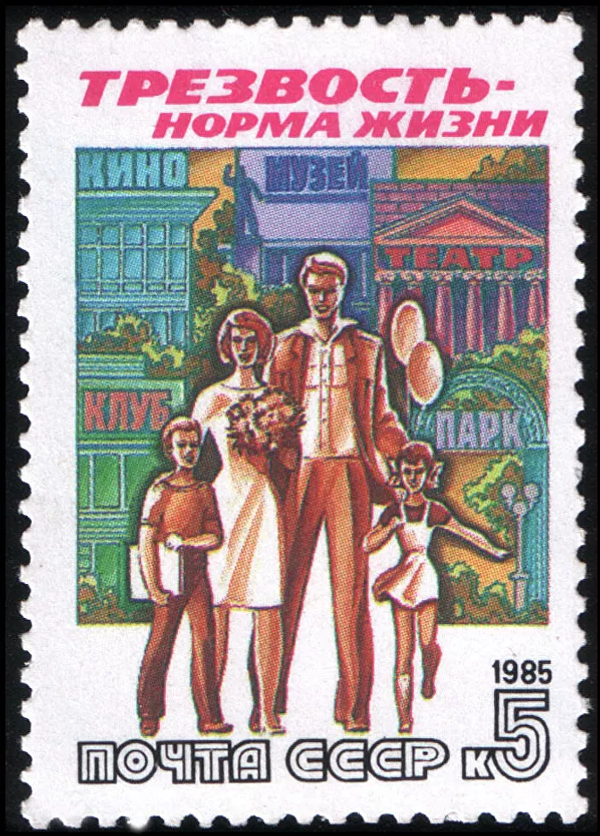

- A campaign to educate the public on the dangers of alcohol consumption and encourage a healthy lifestyle, including the promotion of events such as ‘alcohol-free weddings’ and other social occasions traditionally featuring alcohol, and censorship of the consumption of alcohol in songs, TV and films.

- The destruction or mothballing of alcohol-producing facilities, including, controversially, the crude bulldozing of priceless vineyards in wine-producing republics.

- Fines for those caught drinking in public places such as parks, squares and long-distance trains. Those drinking at work would face demotion, dismissal and, if they were a party member – expulsion from the party.

Reforms Require a Sober Society

The decision to carry out the campaign was made by then newly-elected General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and Egor Ligachev, a conservative teetotaler member of the politburo who abhorred the social consequences of excessive drinking on Soviet society. These included rising alcohol-related illnesses and deaths, road accidents, domestic abuse, declining work productivity, and other social ills.

Formally, the anti-alcohol campaign was wrapped up in the banner of Gorbachev’s broader ‘perestroika’ – an effort to ‘restructure’ and liberalize Soviet society. Several weeks before the campaign was announced, on March 23, 1985, Raisa Goryunova, a worker from Saratov, sent a letter to Pravda, the Soviet Union’s main newspaper, asking that something be done about the “insolent drunks” she encounters daily in the courtyard of her factory. Her letter, published under the headline ‘Sobriety – the norm of life’, would become the main slogan of the anti-alcohol campaign. The letter was published the same day that Gorbachev announced perestroika.

Not everyone in the politburo agreed with the campaign. Eduard Shevardnadze, the Communist Party boss from the sunny republic of Georgia, who would soon become the Gorbachev’s minister of foreign affairs, lamented the destruction of vineyards. Deputy Minister of Finance Viktor Dementsev warned that the ban would deprive the budget of 16 billion rubles (equivalent to about $27.7 billion in today’s dollars) per year. But Gorbachev insisted, and Ligachev stressed that only a sober society would be capable of reform.

Good Intentions

Despite the Soviet leadership’s best efforts, the campaign almost immediately gained public scorn, particularly after rumours began to swirl that vine-growing regions were witnessing the wholesale destruction of vineyards which had been carefully cultivated over many decades.

Unfortunately, as much as 30 percent of wine-producing grapes were destroyed in the Ukrainian, Moldovan, Georgian and Russian republics, some of them containing unique cultures which have proven impossible to recreate to this day. Dr. Pavel Golodriga, respected viniculturalist and director of the renowned Magarach winery in Crimea, committed suicide in 1986 after failing to convince Moscow to save his life’s work.

In Soviet Ukraine, some 60,000 hectares of vineyards were cut down. Only the direct intervention by conservative politburo member Vladimir Scherbitsky stopped further destruction. In the Moldovan republic, 80,000 hectares from its 210,000 hectare total were destroyed. In Georgia, meanwhile, the campaign proved less destructive, with smaller producers merely halting exports and shifting to low-key home consumption.

The campaign’s goal of improving work discipline also proved a fiasco, with workers skipping work to line up outside of stores in the mornings, and brawls breaking out occasionally amid tensions over limited supplies.

Sugar, a key ingredient in moonshine, disappeared from many stores, as did various chemicals containing alcohol or other stimulants. The restrictions led to a spate of poisonings from bad vodka sold on the black market, with 44,000 people poisoned in 1987, 11,000 of them fatally. The campaign also led to a dramatic rise in a phenomenon previously little heard of in the Soviet Union: drug addiction, with drug use among people registered by the ministry of health growing from 9,000 to 20,000 between 1985 and 1987.

All told, the colloquially named ‘dry law’ became a massive strain on the budget, with annual food retail turnover falling by billions of rubles, from 60 billion rubles in 1985 to 38 billion rubles in 1986 and 35 billion in 1987.

The drop forced cuts in health care, science, education and agriculture. Furthermore, the semi-ban on alcohol complicated relations with members of the Comecon, the Soviet-led economic bloc, with Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria deprived of hundreds of millions of dollars in income from the export of wine to the USSR.

Results: Not Great, Not Terrible?

In 2015, Gorbachev admitted that the dry law was a mistake, and what was needed wasn’t a ham-fisted campaign, “but a systematic, long-term fight against alcoholism. The sobering up of society cannot be carried out in a hurry. It needs many years to happen.”

By the late 1980s, in the face of a series of disastrous economic reforms, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, low oil prices, and other calamities, the anti-alcohol campaign was quietly curtailed, with the process begun in 1987. Restrictions on time of sale were not repealed until July 1990.

Ultimately, the campaign stimulated the growth of the shadow economy, including the accumulation of capital among black market speculators which would explode in the privatization schemes of the early 1990s, with estimates that as many as 397,000 people had become engaged in moonshine production by 1987, up from just 30,000 before the campaign began. In public consciousness, meanwhile, the dry law was widely seen as an absurd measure directed mainly against ordinary people, forcing them to wait in long lines or turn to shady black market sellers to get booze at huge markups.

In his 1997 memoir ‘Fate of an Intelligence Officer’, former KGB deputy chairman Viktor Glushko summed up the results of the campaign from the security perspective:

“[The campaign led to] a whole bunch of problems: an astronomical jump in illegal shadow incomes and the accumulation of initial private capital, a rapid growth in corruption, the disappearance of sugar from stores for the purpose of home brewing…In short, the results turned out to be the exact opposite of what was expected, while the treasury was deprived of huge amounts of money which proved impossible to reimburse.”

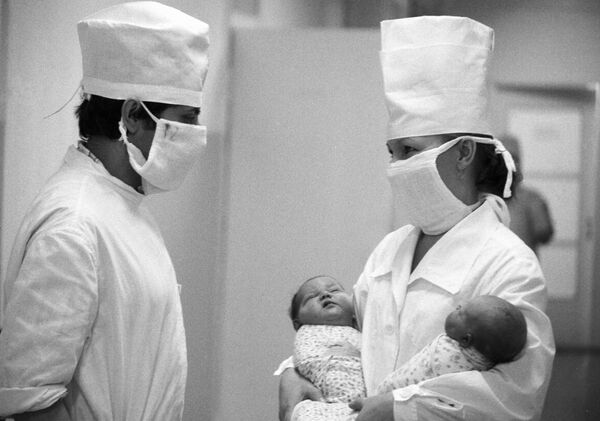

On the plus side, however, statistics show that the decline in alcohol sales did help the country reach its highest-ever life expectancy, which shot up from 67.5 to 70 years in the Russian republic between 1985 and 1987.

Even more significantly, the dry law led to an increase in fertility, and the birth of roughly half a million more children per year during its three first years than at any other time over the previous three decades. These children were also healthier, with eight percent fewer immunocompromised births recorded in 1987. A drop in crime rates was also recorded.

Unfortunately, after the USSR’s collapse, alcohol consumption exceeded pre-1985 levels by 1994, helping to lead to the catastrophic increase in mortality rates observed throughout the 1990s. After that, it would take Russia more than two decades to bring average alcohol consumption down to pre-dry law levels, with consumption falling to 10.5 litres per capita per year (the same level as it was in 1985) in 2015.