After years of exoplanet-hunting, researchers have made a breakthrough calculation suggesting there could be a myriad, as many as 6 billion, Earth-like planets orbiting Sun-like stars in the Milky Way, according to a study published in The Astronomical Journal.

"My calculations place an upper limit of 0.18 Earth-like planets per G-type star", said astronomer Michelle Kunimoto from the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Canada, who is known to have recently made another phenomenal discovery - 17 exoplanets in Kepler telescope data.

Overall, the research team determined the new finds measuring between 0.75 and 1.5 times the mass of Earth, and orbiting a G-type star, typically referred to as a yellow dwarf, at a distance somewhat between 0.99 and 1.7 astronomical units (AU, the distance between Earth and the Sun).

At the upper limit of the G-type star estimates - a figure that has been roughly pinned down- the calculations arrived at a maximum of 6 billion such exoplanets, although this might be a far cry from reality, the researchers believe. They admit these planets do not necessarily have life forms thriving on them, like the case with life-empty Mars, which lies 1.5 astronomical units from the Sun.

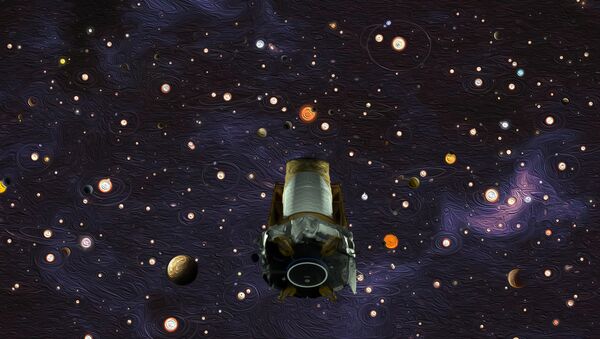

To locate the missing planets the team used a technique known as forward modelling to simulate data based on the model's parameters: throughout the research, the scheme was applied to a catalogue of 200,000 stars studied by the Kepler planet-hunting spacecraft that ploughed through space from 2009 to 2018.

"I started by simulating the full population of exoplanets around the stars Kepler searched", Kunimoto said, adding she marked each planet as “detected” or “missed” depending on “how likely it was my planet search algorithm would have found them".

The researchers believe that in-depth analyses of how common certain types of planets are around stars are of extraordinary promise as they “can provide important constraints” on how planets form and evolve, as well as help optimise further missions aimed at finding new exoplanets.

Last month, a team of astronomers from Cornell University in the United States proposed a new way to determine whether an exoplanet is potentially habitable. As per the study, published in the scientific journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, the novel approach is based on a planet’s surface colour and the amount of light it reflects.

For instance, if a planet is rocky and made of black basalt, it will absorb more light and hence have a hotter temperature, while by contrast, a sandy surface surrounded by clouds reflects more light, so the overall temperature of the planet will be cooler than that of the rocky, basalt one.