Policymakers and academics in India have begun a debate in the wake of the prolonged lockdown, which interrupted the current academic year, over whether or not it is time for India to take advantage of existing technology and shift to online education. They were forced to reflect on a grim reality: in India, a sizeable proportion of the population has no access to internet or television networks to access online classes.

“Yes, as the old adage goes, every crisis presents an opportunity as well. As the future lies in digital education, it is only natural that there should be momentum towards that end. COVID-19 only accelerated our journey towards that goal in a sudden manner. The public health challenges, social distancing and lockdown requirements have left us with no other choice,” said Professor Y.S.R. Murthy, Registrar of O.P Jindal Global University on the outskirts of New Delhi.

Professor Murthy, however, said India cannot just seize the opportunity to pursue an online system of education. It needs to be fully cognisant of the many prerequisites for a fully effective online system of education.

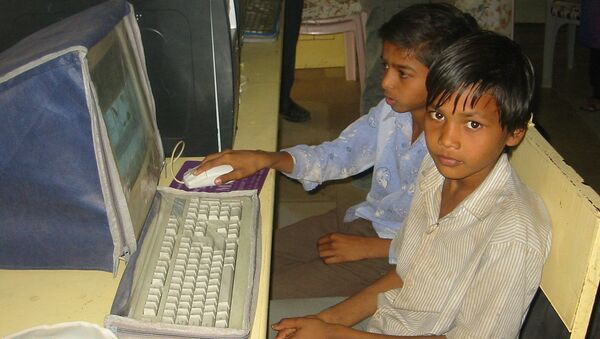

“Firstly, the teachers need to be ready for the switch and must be adept in the technology. Secondly, the issue of assessments in the online system is a grey area which needs to be addressed. Thirdly, internet penetration and the digital divide are an important gap in universal coverage. Fourthly, students pursuing science subjects require laboratories; although there is a talk of virtual laboratory, its own effectiveness vis-a-vis the physical one is shrouded in doubt,” explained Professor Murthy.

Professor Pankaj Mittal, Secretary General of the Association of Indian Universities, an umbrella body of all major universities in India, said right now it was compulsory due to the prolonged lockdown.

“We cannot think that all the universities and colleges would close and only work online. Right now it is compulsory, there is no other option and therefore, it is okay. The future should be a blend of physical and online education,” she said.

“I believe that in the future more technology would be there than buildings. Future universities would be technology-based,” felt Mittal.

Professor Mittal, who was earlier Vice Chancellor of India’s first rural women's university, suggested an alternative to fill up the urban-rural divide in the country. She said the government should set up common facilities at the village-level, with access to technology, which can serve as digital classroom for students who can't afford private facilities at home for an online education.

Professor Murthy had a different view. He felt online education would accentuate the class divide in India.

“The class divide will be further exacerbated the learning divide. Though COVID-19 has forced many educational institutions to switch over to online classes, we need to be fully cognisant of those who do not possess smart phones, laptops, I-pads, etc. or a functional internet system with good bandwidth which enables live streaming. These issues need to be fixed in a timely manner, whether we are affected by coronavirus or not. When we shift to online classes, there is a need to create a support system for those who could miss its benefits,” he suggested.

India’s student-age population is estimated to be around 400 million, a sizeable percentage of this figure live in rural areas. Though the government has claimed India’s 597,464 villages have been provided with electricity, it is not an indication that every household has access to electricity.

India has approximately 504 million internet users, who are five years or older, out of a population of over 1.38 billion. According to the latest report by the Internet and Mobile Association of India, rural India had 10 percent more internet users than urban areas.

On the other hand, only 46 million households have access to television according to a report by the consulting firm Ernst and Young.