The Milne Ice Shelf is a fragment of the former Ellesmere Ice Shelf located in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada.

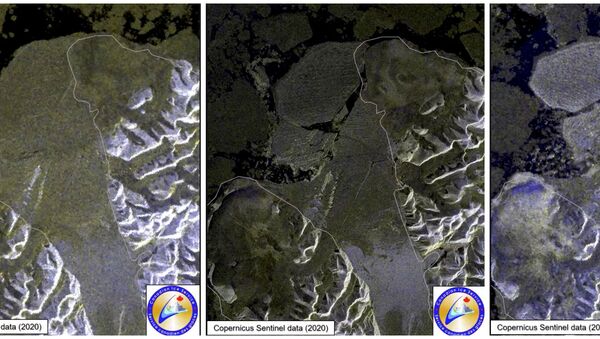

The shelf’s area shrank by around 80 square kilometers. In comparison, Manhattan in New York covers an area of about 60 square kilometers.

"Entire cities are that size. These are big pieces of ice," said Luke Copland, a glaciologist at the University of Ottawa who was part of the research team studying the Milne Ice Shelf, Reuters reported.

"This was the largest remaining intact ice shelf, and it's disintegrated, basically," Copland added, also noting that this year’s summer in the Canadian Arctic has been warmer than usual: 5 degrees Celsius higher than the 30-year average.

According to the Canadian Ice Service, “above normal air temperatures, offshore winds and open water in front of the ice shelf” have all contributed to the formation’s collapse.

The unusually warm season also makes it likely that smaller ice caps are in danger of melting, as unlike larger glaciers, they don’t have the mass needed to remain cold.

"The very small ones, we're losing them dramatically," Copland explained. “You feel like you're on a sinking island chasing these features, and these are large features. It's not as if it's a little tiny patch of ice you find in your garden."

The Arctic has been warming at twice the global rate for the last three decades due to a process known as Arctic amplification, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reports.

According to NASA, temperatures warm faster in the Arctic than the rest of the world because when “bright and reflective ice melts, it gives way to a darker ocean.”

“This amplifies the warming trend because the ocean surface absorbs more heat from the sun than the surface of snow and ice. In more technical terms, losing sea ice reduces Earth’s albedo: the lower the albedo, the more a surface absorbs heat from sunlight rather than reflecting it back to space,” NASA explains on its website.

Earlier this summer, two of Canada’s ice caps located on the Hazen Plateau in St. Patrick Bay also disappeared completely, two years earlier than they were predicted to do so, according to environmental outlet Yale Environment 360.

“When I first visited those ice caps, they seemed like such a permanent fixture of the landscape,” Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, said in a statement. “To watch them die in less than 40 years just blows me away.

Two other ice caps on Ellesmere Island, known as Murray and Simmons, are also diminishing and could completely melt within the next decade, Reuters reported.