The US National Aeronautics and Space Administration is tracking an immense, growing, and slowly splitting "dent" in the Earth's Magnetic field.

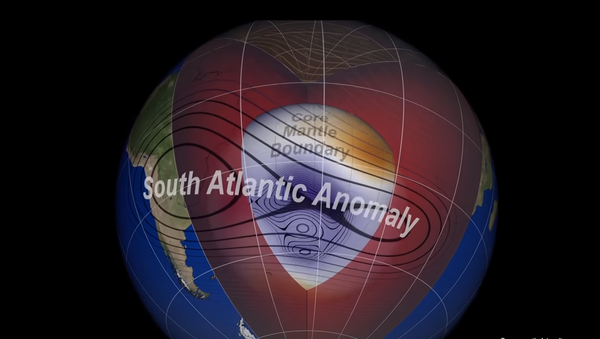

The area, known as the South Atlantic Anomaly, is situated in the southern hemisphere between South America and the southern Atlantic Ocean off the coast of southwestern Africa. According to recent NASA monitoring and modeling, the area is expanding westward and becoming weaker, and expected to completely split into two separate cells, each spanning thousands of kilometres across, soon.

NASA says the weakening of the magnetic field in this area threatens to allow more solar radiation to get closer to the surface of Earth, disabling electronics or scrambling or temporarily disabling satellites and other space-based man-made objects that pass through it.

In modeling running through to the year 2025, NASA predicts that the South Atlantic Anomaly will continue to grow, with the larger of the two globes continuing to spread over central South America, and the smaller remaining off the southwest coast of South Africa.

Earth's protective magnetic field is generated by a number of factors, the most important being the churning of liquid iron flowing inside the planet's core, which create the electrical currents sent outwards into near space to create the field.

It's believed that a massive reservoir of dense rock known as the African "Large Low Shear Velocity Province", or African superplume, causes a disturbance in the field's generation, resulting in a regional weakening of the magnetic field. A second massive superplume is located under the Pacific Ocean northeast of Australia.

Last year, the rapid shifting of the coordinates of the magnetic north pole out of the Canadian Arctic toward Siberia prompted some scientists to express concerns that Earth could be in for a flip of its magnetic north and south poles. The last such flip is thought to have taken place around 780,000 years ago, and scientists still don't fully understand how such a phenomenon would affect the magnetic field.

Even with the magnetic field intact, human civilisation remains vulnerable to sudden bursts of powerful solar radiation. In 2011, US academics warned that a repeat of a solar storm similar to that which hit Earth in 1859 could cause as much as two trillion dollars in initial damage, damaging electrical power grids, satellites, navigation systems, etc. However, others have sought to calm fears of a flip, estimating that such a process may take as much as a thousand years to complete, thus dramatically reducing its negative impact.