Archaeologist Dr Chris Naunton has shared with the Express some insights into one of the most stunning discoveries in Egyptology, the Great Pyramid of Giza, which is believed to have been constructed for Pharaoh Khufu over a 20-year period, although his body has never been recovered from the area.

Five years ago, the ScanPyramids project was launched to provide several non-invasive and non-destructive techniques that would improve historians’ understanding of how the pyramid was constructed over 4,500 years ago. Two years later, they solemnly announced the discovery of a “Big Void” - an intriguing 30-metre cavity located above the Grand Gallery. However, there has been no development since, and Dr Naunton, the author of Searching for the Lost Tombs of Egypt, does not expect there will be headway any time soon, fearing the contents of the pyramid will continue to be hidden from the public eye.

“The area around it has been very extensively excavated, there are parts of Giza that still haven’t been thoroughly excavated, but I don’t think they are likely to tell us huge amounts”, the archaeologist shared, dwelling on the discovery of the landmark void that stirred the researchers' overwhelming enthusiasm.

While Naunton is keen to take a look inside, he said there are currently too many restrictions in place.

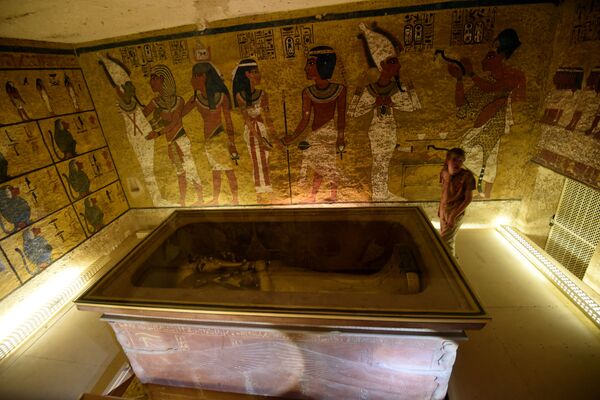

“The problem is, as with the anomaly in Tutankhamun’s tomb, until you can go and get in it, there’s nothing you can really say”, he noted.

He went on to single out the two places in the country that raise the most questions, but largely put Egyptologists off - Giza and the Valley of the Kings. At the Great Pyramid, there is hardly anything that can be done "with all the red tape around it”. Separately, Giza attracts bunches of theories about mystic energy, aliens, and alike - something that makes the archaeological spot “even worse”.

“The Valley of the Kings isn’t like that, it’s just lots of gold and excitement”, he went on, enumerating other spheres of interest for Egyptologists.

“But in other parts of the country, there are loads of really good information and potential to go and do work without the hullabaloo of the sensation attached to those two”, Naunton contended, welcoming research there as well.

The historian had previously put forward a possible solution to finally make a huge discovery.

“Would it be possible to put a fibre-optic camera through the wall and see what’s behind there? That seems to me to be a solution”, he claimed, suggesting that it might even be possible to do that without causing too much damage to the wall, which has already been extensively renovated. Whatever the case, even if technically possible, Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities would be very wary of the public reaction to putting a camera through the wall, “only to find there’s nothing there”, Naunton rounded off.