US President Donald Trump's campaign attorney on 7 November demanded recounts in every state using the Dominion Voting Systems vote-tallying machine software that erroneously “flipped” 6,000 votes to Democrats in one Michigan county from the Republicans, as Trump continues to question the legality of vote counting in key battlefield states that are under scrutiny.

Timothy Hagle, a political science professor at the University of Iowa, has offered his views on the Dominion Voting System, potential issues with electronic vote counting, and possible alternative solutions to avoid potential voter fraud.

Sputnik: Toronto-based Dominion Voting System was rejected by Texas Secretary of State in 2019 for major flaws in their software. Why was it used this election in 6 battleground states and 22 others?

Timothy Hagle: You can find the Texas report on the Dominion software here.

The report details several potential problems with the software, such as a complex installation process and potential problems dealing with human error. On the plus side, the report notes that the use of off the shelf components would reduce the expense of the overall system.

Along those lines, if the Dominion system was much less expensive then cost may have been a more important factor in making their decision.

Sputnik: How potentially serious can problems with electronic vote counting be?

Timothy Hagle: The key word in that question is "potentially". Potential problems with electronic voting can range from losing all vote information that might be stored on the system, to a system that inaccurately records votes as they are cast. Any problem that people have had with computers and software could possibly happen with an electronic voting system.

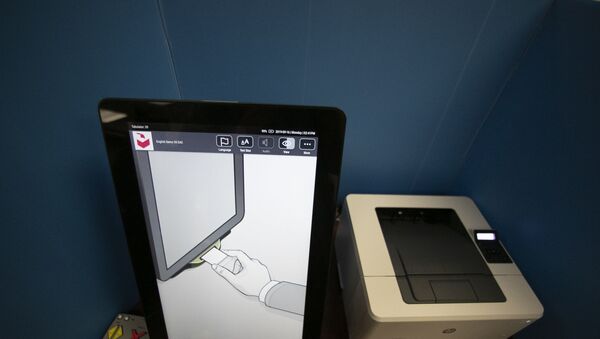

Of course, and as with any computer or electronic system, you would want to design the system to handle every potential problem you can think of. That means problems with the hardware (view or touch screens, printers, scanners, storage systems, network infrastructure, power backup, etc.) and the software (installation, handling different voting situations, protection from hacking) have to be anticipated and worked out in advance. As part of this, the system must account for a wide variety of user errors.

For the most part, developers of electronic voting systems will be aware of the various problems and work to allow their systems to overcome them. Even so, as Texas determined, there may still be shortcomings with any system and it may be seen as serious enough that a state might not want to use such a system.

Sputnik: In your opinion, what kind of counting system should be followed to avoid situations with voting fraud? What system can satisfy both sides of the electoral process?

Timothy Hagle: As to the first question, no system will be perfect. Aside from voting fraud, meaning purposeful attempts to rig or hack the system, any system must also account for simple human error at both the voting and counting levels. The desire for electronic voting is understandable as it is certainly faster than using traditional paper ballots. If the software works correctly, then there should be a record of each voter's selections. Unfortunately, electronic data can be corrupted or lost unless significant protection procedures are in place. That's one reason why some people argue that paper ballots should always be used as they provide a backup of the original data that can't be corrupted. Of course, paper ballots have their own problems, such as if they are not stored properly or are lost or destroyed.

As much as many states have moved to electronic systems, the emphasis on mail-in voting due to the pandemic meant that a larger than usual number of voters ended up using paper ballots this election. In my state, Iowa, those who voted on election day still used a paper ballot that was run through a scanner to record their vote. That wasn't too different from voters who chose to use a mail-in vote because their ballots were the same and were also run through a scanner to record their vote.

In contrast, states that may have used an electronic system for Election Day, may have then had the electronic input printed on a ballot which was then run through a scanner (which seems to be what the Texas report was describing), but voters who used a mail-in ballot did not have to deal with the initial electronic interface. That meant that states using such a system had to effectively deal with two systems, one with and one without the initial electronic component.

On the whole, no system is going to be perfect. There will probably be ways any system could fail or have problems under the right conditions. Sometimes it could be due to human error of one sort or another. Other times the system may be vulnerable to those who intentionally wish to commit fraud. Given a desire to get as many people as possible to legally vote and considerations such as cost, speed, and efficiency, we just have to do our best to anticipate as many problems and weaknesses as possible and do what we can to guard against them.