New analysis of an ancient papyrus, the First Book of Breathing, has offered fascinating revelations pertaining to its derivation from the Book of the Dead and, on a broader scale, the intricacies of postmortem deification in ancient Egypt, writes Haaretz.

The Books of Breathing are several late ancient Egyptian funerary texts, that ostensibly enabled the deceased to continue to exist in the afterlife, with the earliest known copy dating to about 350 BC.

Book of the Dead papyrus #Pinedjem II

— Sarah Scott (@sarahdawnscott) September 13, 2014

21st Dynasty

Deir el-Bahri

EA 10793/1@britishmuseum#Osiris #EgyptianGods pic.twitter.com/OBltJ6S6Xn

Other copies originate from the Ptolemaic and Roman periods of Egyptian history; one is from the second century AD.

An analysis of one such treatise – Papyrus FMNH 31324, containing an edition of the First Book of Breathing, was recently published by Foy Scalf, head of Research Archives at the University of Chicago, in October’s edition of the Journal of Near Eastern Studies.

Managing the Afterlife

The Book of the Dead began to appear around 3,700 to 3,500 years ago, with the subsequent emergence of three types of Book of Breathing manuals on how to achieve deification in the afterlife, Scalf is quoted as saying.

The “Letter for Breathing”, believed to have been written by ancient Egyptian goddess Isis for her brother Osiris; the First Book of Breathing; and the Second Book of Breathing – these are the three Books of Breathing which were intended to help the owner of the text join the gods in the afterlife.

They were either inscribed on a pyramid wall, or coffin, or on a papyrus.

The texts were not canonical and represented something in the manner of a collections of spells written on papyri, with all of them varying in wording and illustrations, as did the Books of the Dead. The latter were Egyptian mortuary texts made up of spells, placed in tombs and believed to protect and aid in the afterlife.

According to Scalf, the texts on pyramids, coffins, and in the Book of the Dead are all related. The three Books of Breathing were almost exclusively handwritten on papyri, with basically similar contents.

The instructions varied, with “Letter for Breathing” telling the user to roll up the papyrus, wrap it in linen and place it under the mummy’s left arm.

The First Book of Breathing instructs that it should be placed under the head; the Second Book of Breathing suggests the text be placed under the feet.

Contrary to some assumptions, deification was not so much a privilege of the elites, as of anyone who could afford it.

“Burials in ancient Egypt ranged from simply being placed in a shallow hole in the desert all the way up to sumptuous tombs, and everything in between. As far as we know, what was provided for you at death was related to your wealth in life,” says Scalf.

However, the mighty pharaohs didn’t need texts on papyrus.

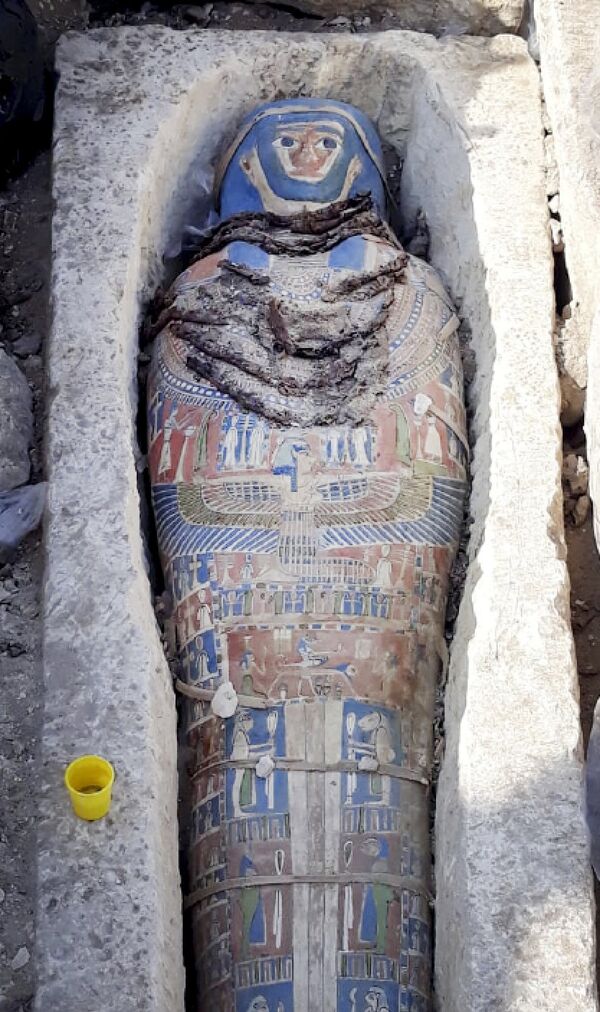

“Royalty had their spells placed on more robust media such as tomb walls, sarcophagi, coffins, masks, statues, and anywhere else the texts could be inscribed,” notes Scalf.

Mereruka vizier’s funeral statue in front of his false door at his Saqqara tomb. Reign of Teti. Old Kingdom, 6th Dynasty, ca. 2345-2181 BC. pic.twitter.com/YaD26OmQMa

— zoli osaze (@zaswadosaze) April 24, 2018

Individualized Funerary Rites

While mortuary papyri were individualised to bear the name of the dearly departed at the beginning, saying: “This First Book of Breathing is placed under the head of…”, the papyrus FMNH 31324 unfortunately has the first column of text missing.

Another thing that differentiates the books is that in the Book of the Dead the individual spells - how to breathe and drink water, or how to navigate the underworld - are separated and entitled, says the head of Research Archives at the University of Chicago.

While the First Book of Breathing took its origins from spells in the Book of the Dead, the content was edited and reshaped.

The result was a single continuous composition, with much reedited by the scribes themselves.

“The scribes were very keen on what they were putting in and leaving out,” he says, adding that the selected spells are given in the same order as in the original Book of the Dead.

Ancient Egyptian papyrus showing a part of the Book of the Dead of Pinedjem II. The text is hieratic, except for hieroglyphics in the vignette. The use of red pigment, and the joins between papyrus sheets, are also visible.

— MEHMET ARIKAN (@lastarchaeology) August 20, 2018

New Kingdom

Dynasty 19 ca. 1300 BCE

British Museum pic.twitter.com/Jz8pGe1MKo

Papyrus FMNH 31324 contains an abridged version of the First Book of Breathing, says the scientist, underscoring that the manuscript is “on the whole, well-written and free from egregious scribal errors”.

Foy Scalf concludes that as in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods of ancient Egypt, which is when the Books of Breathing were used, most burials were multiple, with several mummies placed in a single tomb, the Breathing papyri were seemingly wrapped up with the mummy itself, possibly to ensure the spells do not erroneously affect the wrong body.