On Tuesday, peer-reviewed medical journal The Lancet published an interim analysis from the phase 3 trial of the Russian vaccine, showing its 91.6 percent efficacy against symptomatic COVID-19. The vaccine is also 91.8 percent effective for people aged over 60, and none of the rare serious adverse effects had been deemed to be associated with the vaccine, with most of the side effects being mild flu-like symptoms.

"I think it is a good, well-conducted trial. The data are sound. You cannot see any obvious problem with it, 91.6 percent efficacy puts Sputnik V up in the top-flight vaccines that have [been] reported so far," Livermore, who is a professor of medical microbiology at the UK University of East Anglia, said.

Commenting on the probable approval of the vaccine's use in the European Union in early March, the professor said that the entire world, including Europe, which is experiencing disruptions in the imports of COVID-19 vaccines, needs every available vaccine.

"The world needs all the good vaccines that it can get. That includes continental Europe, the European Union, which has not made a good job of its vaccine procurement," Livermore said.

The medical scientist went on to explain that all the existing vaccines against COVID-19 could be divided into four types: those that use classic technology of inactivated virus, such as China's Sinopharm and Sinovac; those that take the spike protein from the virus, reform it into nanoparticles and inject it as a vaccine, such as the vaccine by the US' Novavax; messenger-RNA vaccines, such as those developed by Moderna and Pfizer, and adenovirus vector vaccines, such as Sputnik V, the vaccine by AstraZeneca-Oxford, and Johnson&Johnson's upcoming vaccine.

"Interestingly, out of these [adenovirus vector vaccines], Sputnik V has come up with 91.6 percent efficacy, whereas AstraZeneca and Johnson&Johnson are having 60 percent efficacy. So, Sputnik V has come up significantly the best of these three adenovirus vector vaccines," Livermore said.

However, the scientist could not single out one type of vaccine that provides the best protection.

"One could argue that, perhaps, the ones that use the old technology, inactivated virus, might, in theory, have an advantage over spike-protein vaccines if we get different variants because they will also give some immunity to other components of the virus. But that is purely theoretical. The messenger-RNA, the adenovirus, and nanoparticle, Novavax, could all be adjusted to cover virus variants in the future," Livermore added.

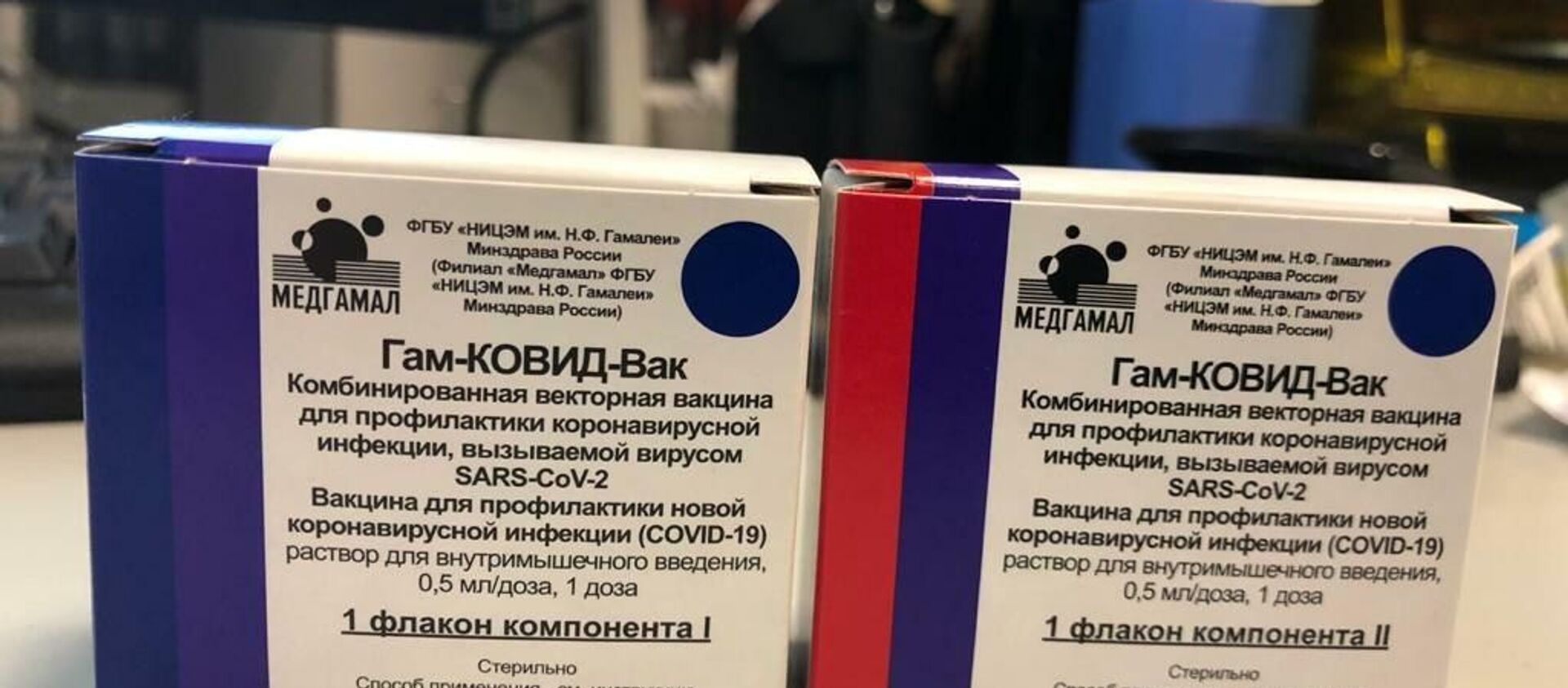

Sputnik V, developed by the Gamaleya Epidemiology and Microbiology Center and registered by the Russian Ministry of Health on August 11, was the world's first vaccine against the novel coronavirus. The vaccine consists of two components that are applied to a person within an interval of 21 days. The phase 3 trial included over 20,000 adult volunteers, and is still ongoing, as it aims at including 40,000 participants.

Trial on Mixed Sputnik V-AstraZeneca Dosing Ongoing, May Lead to More Efficacy

Kirill Dmitriev, the CEO of the Russian Direct Investment Fund, said in early January that plans were in place to conduct mixed Sputnik V-AstraZeneca dosing regimen trials, as the Russian vaccine showed better results. According to the scientist, the highest efficacy of Sputnik V among the existing adenovirus vector vaccines, which also include vaccines by AstraZeneca and Johnson&Johnson, may be caused by the usage of different vectors, different carrier adenoviruses for shot-1 and shot-2 of the Russian vaccine. AstraZeneca's vaccine, instead, uses the same chimpanzee adenovirus in shot-1 and shot-2.

"One trial that has now been set up between Gamaleya [research institute], the Russian Direct Investment Fund, and AstraZeneca, is that you will get one shot of AstraZeneca and one shot of Sputnik V. That would be another potential way to go. It is going to be a couple of months, I think, before we see any results from it, at least, vaccines are being recruited as of this month. So that will be very interesting. If that is to give a very positive result, that might well lead to a rethink about using different vaccines in combination," Livermore said.

The Russian manufacturer is not the only one AstraZeneca cooperates with to develop better protection from COVID-19. Earlier on Thursday, the UK Department of Health and Social Care said the country had launched recruitment for the world's first clinical trial that would see volunteers given alternating doses of COVID-19 vaccines produced by AstraZeneca/Oxford University and Pfizer/BioNTech. The scientist said that he welcomed any collaborations that would help fight the pandemic.

"We all worldwide face a considerable challenge from this virus, from the various mutants it is throwing out, so it is well worthwhile that we look at the best ways of collaborating," Livermore said.

"However, you do have immune memory cells, B cells, which retain the memory of how to make the antibody and hopefully will switch on if you are going to get an infection, and you also have a T cell response, and we know that that persists longer in circulating antibodies. So the reasonable expectation is that vaccine-mediated protection should last more than six months and hopefully more than a year," Livermore said.

As for protection against mutations of the novel coronavirus, the scientist said that it was also not clear yet how effective the existing vaccines could be effective against them.

Most of the vaccines have the spike protein, which is on the surface of the virus, as their target. In case new variants modify it in the future, the vaccines may become less efficient or even inefficient at all in the worst-case scenario.

"The best information we have is from the Novavax vaccine, which was trialed in the UK when the Kentish variant was already circulating, and it seemed to give as good a protection against the Kentish variant as against the generality of COVID," Livermore said.

At the same time, the vaccine seems less effective against the strain originating in South Africa — shows about 60 percent rather than 89 percent efficacy. This suggests that the South African variant may be able to get around the vaccines that are based on the spike protein to a degree. However, even 60 percent of vaccine efficacy would in any case be enough to keep herd immunity in the population, the specialist added.