Before the Arab Spring, Libya was the most prosperous country in Africa, enjoying the strongest Human Development Index (HDI) figures, the lowest infant mortality, and the highest life expectancy on the continent.

Today, Libya is divided among multiple warring factions, has areas with open air slave markets, and serves as a hotspot for immigrants and refugees willing to risk life and limb to make their way to Europe. Despite its wealth in energy resources, wide swathes of the country remain cut off from gas, electricity, and water.

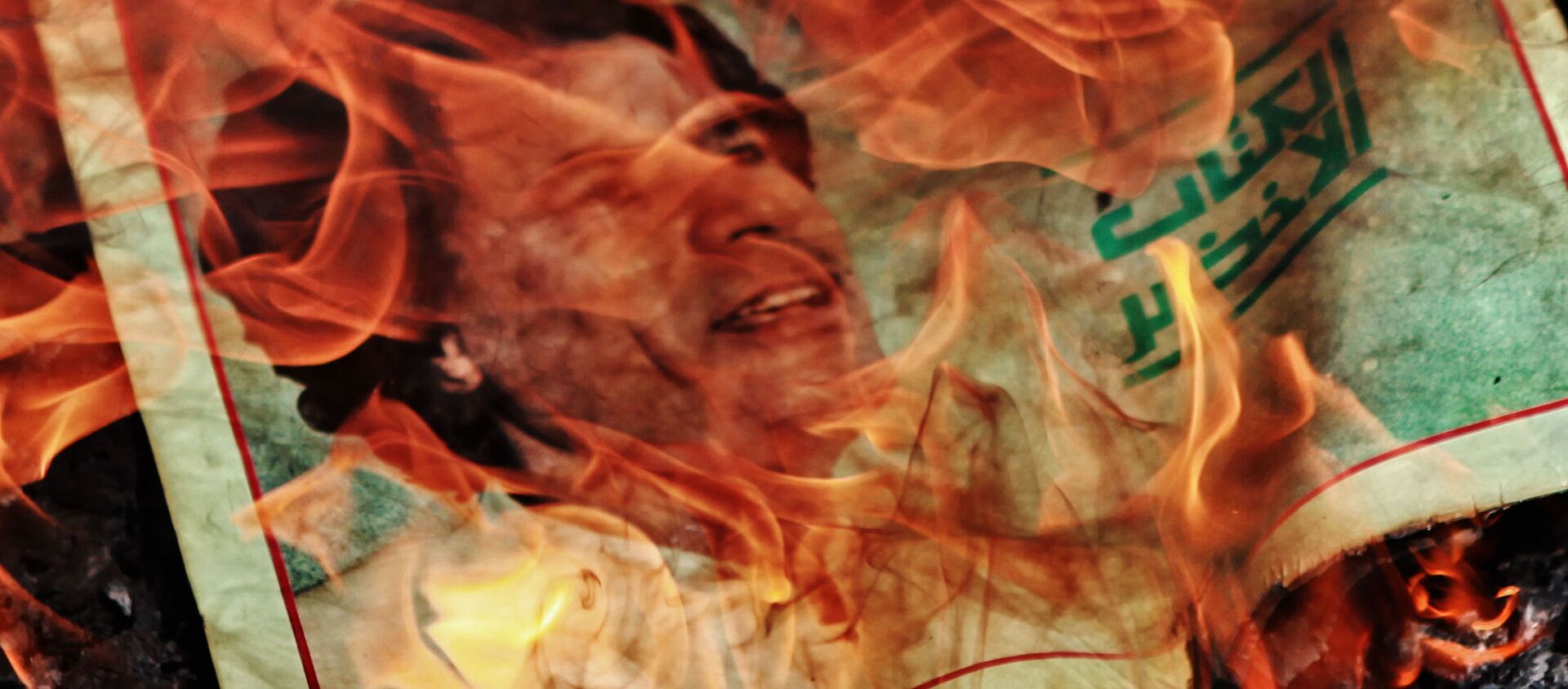

Ten years since the February 2011 Benghazi protests that would eventually lead to the collapse of the Gaddafi government, dubbed the Libyan “Revolution” by Western media, many Libyans are cynical about the fruits of the chaos and unrest that the ‘revolution’ has brought with it.

“There was no ‘revolution.’ The chaos in which we live was only the consequence of the redrawing of the region by external players. This is clear when one looks at what forces are present in our country, and for what reason,” says Hussein Miftah, a Libyan writer.

“Branches of the Muslim Brotherhood control part of Libya’s territory. Naturally, they could not even have dreamed about this before. Now they are supported by Turkey, which sends them money or weapons. They also cooperate with other extremists movements of political Islam in North Africa, and are enjoying a real flourishing,” Miftah explains.

Libya declared independence in 1951 after twelve years under French and British occupation. Before that, the country was colonised by Italy in 1911, and occupied until 1943. Until the early 20th century, Libya was part of the Ottoman Empire for over three-and-a-half centuries.

‘Black Period’ in History

Naser Said, a spokesman for the Libyan Popular National Movement, a political party set up by former Gaddafi-era officials in 2012, says the 2011 uprising pushed back Libya’s development decades. “The events that took place returned the situation inside the country to what it was in the 1950s – with Libyans made to live without electricity, without medicines, without money.”

Calling the events of February 2011 a “black period” in the history of the Libyan people, Said stresses that Libyans must now return their country’s independence from the hands of foreign governments and terrorists, although it is unclear how or when this can take place.

“Ten years ago Libya’s enemies – both foreign and domestic, tricked people into taking to the streets, organising a ‘revolution,’ involving the media in this. As a result, we were deprived of our own country; we got eight months of blatant military intervention from NATO. This was the alliance’s largest and longest military operation outside its borders after the Second World War,” not counting Afghanistan, the spokesman says.

“Today we have neither statehood nor infrastructure. Hundreds of thousands of Libyan families have been displaced from their homes, their cities and villages destroyed. Thousands of Libyans were killed in cold blood,” Said emphasises.

New Hope?

Not everyone is equally pessimistic about the consequences of the events of 2011. Adel Karmous, a member of the Tripoli’s High Council of State, an advisory body to the Government of National Accord, suggests Gaddafi’s overthrow was the start of a new page in Libya’s history.

“The Revolution undoubtedly achieved its aims: the regime which only harmed Libyans through its tyranny and oppression for more than 40 years, was finally overthrown. Ten years ago, there was a real revolution of the Libyan people against authoritarianism. This should not even be questioned. Moreover, it was not organised by any third party – the protests were spontaneous,” Karmous insists.

The politician blames the chaos which has followed in the wake of Gaddafi’s ouster on the lack of a clear leader who could take the country’s political transformation under control.

In November 2020, the Government of National Accord and the Tobruk-based House of Representatives – the two largest factions controlling much of the country’s territory, agreed to United Nations-brokered talks to find a resolution to the Libyan crisis. The same month, Tunisia hosted a meeting of the Libyan Political Dialogue Forum (LPDF), featuring 75 public and political figures from across the country. In mid-November, participants of the LPDF agreed on a ‘road map’ for the unification of state authority, and to nationwide elections on 24 December 2021 – the seventieth anniversary of Libya’s independence.

In mid-January, the UN reported that significant progress had been made in talks on the formation of a transitional government. In early February, the LPDF voted to appoint an interim government, with Abdul Hamid al-Dabaib, a Canadian-educated engineer, businessman, and politician, picked as interim prime minister.