A team of deep-sea explorers from the US have set a new record by descending to the world's deepest-known shipwreck for the first time.

Former US Navy commander Victor Vescovo, one of two ex-officers who funded the expedition, personally piloted the submersible DSV Limiting Factor on two separate eight-hour dives to the wreck site of the USS Johnston some four miles (6.5 km) below the surface of the Leyte Gulf in the Philippines.

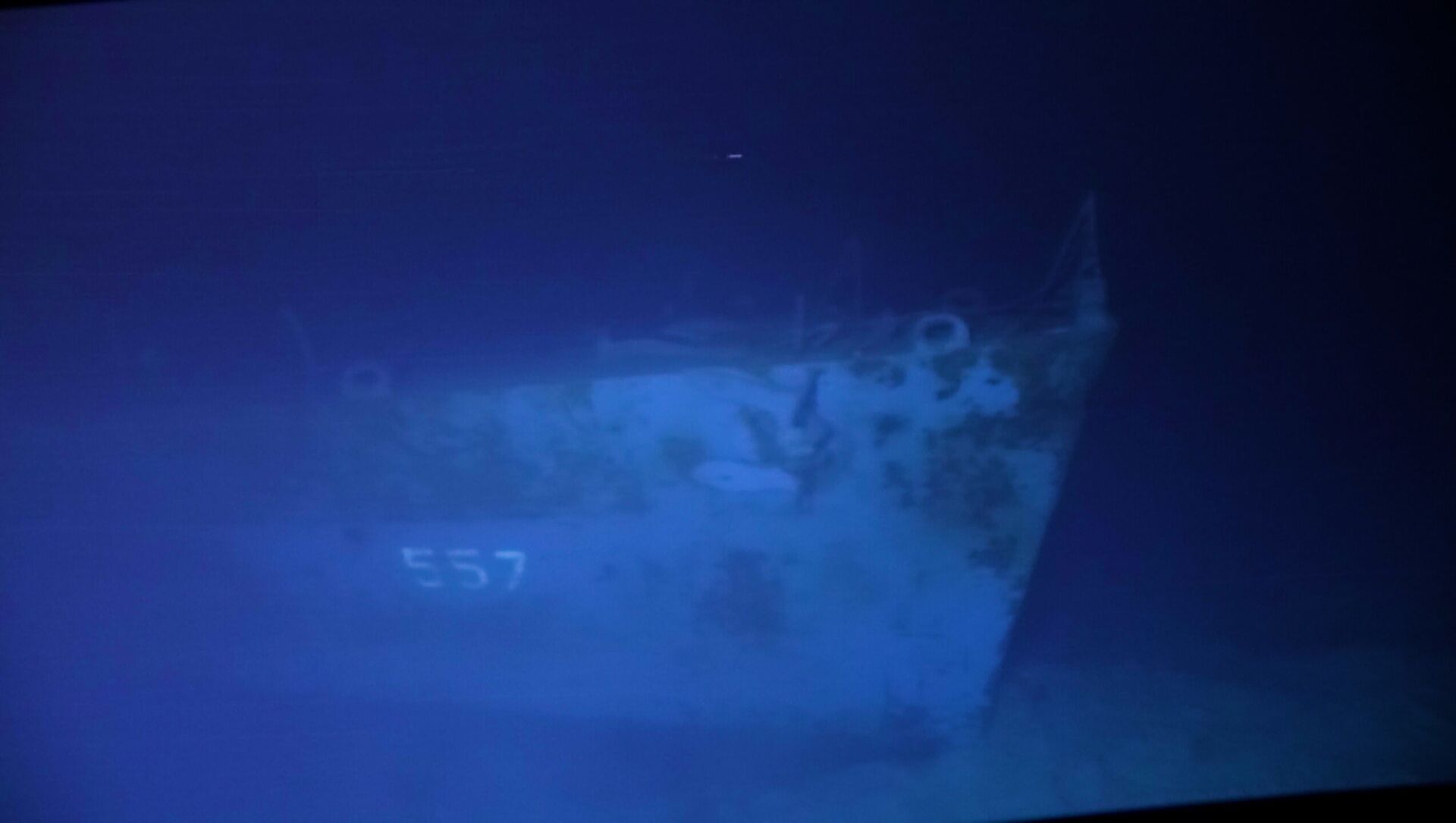

The mariner said the ship was remarkably well-preserved after nearly 77 years. Her painted hull number 577 was still clearly visible on both sides of the bow.

"The wreck is so deep so there's very little oxygen down there, and while there is a little bit of contamination from marine life, it's remarkably well intact except for the damage it took from the furious fight," Vescovo said.

The Second World War destroyer is famed for its crew's sacrifice in fighting a rear-guard action against a far superior force of the Imperial Japanese Navy, including the world's biggest battleship Yamato, on October 25 1944 during the battle of the Leyte Gulf. That allowed the small escort aircraft carriers the Johnston was escorting to escape destruction. She went down east of Samar island with the loss of 186 of her crew of 327.

"We could see the extent of the wreckage and the severe damage inflicted during the intense battle on the surface. It took fire from the largest warship ever constructed — the Imperial Japanese Navy battleship Yamato, and ferociously fought back," said retired USN Lieutenant Command Parks Stephenson, who has extensively researched the ship's history. "All of the accounts pay tribute to the crew’s bravery and complete lack of hesitation in taking the fight to the enemy, and the wreckage serves to prove that.”

"The gun turrets are right where they're supposed to be, they're even pointing in the correct direction that we believe that they should have been, as they were continuing to fire until the ship went down," Vescovo said. "And we saw the twin torpedo racks in the middle of the ship that were completely empty because they shot all the torpedoes at the Japanese."

The team were careful not to disturb the last resting place of many of the crew, and did not see any human remains or clothing during the dive.

“We have a strict ‘look, don’t touch’ policy but we collect a lot of material that is very useful to historians and naval archivists. I believe it is important work, which is why I fund it privately and we deliver the material to the Navy pro-bono,” Vescovo said.

Following the historic dives, the team laid a wreath on the naval battlefield in honour of the USS Johnston's crew.

“In some ways we have come full circle. The Johnston and our own ship were built in the same shipyard, and both served in the US Navy," Vescovo said. "As a US Navy officer, I’m proud to have helped bring clarity and closure to the Johnston, its crew, and the families of those who fell there.”