In a newly released study, researchers have mapped the origins and preliminarily determined the source of a mysterious glow coming from the centre of our Milky Way. The "glow" is believed to come in the form of gamma radiation, which, as new data suggests, is created by "dark matter" – a hypothetical form of matter that could make up roughly 80% of the matter in the entire universe.

"The analysis clearly shows that the excess of gamma rays is concentrated in the galactic centre, exactly what we would expect to find in the heart of the Milky Way if dark matter is in fact a new kind of particle", Mattia Di Mauro, of the National Institute for Nuclear Physics, said.

So, what's this new and undetected sort of particle found in the galaxy's heart?

Back in late 2017, astronomers may have arrived at cues pointing to what dark matter actually is, as a study at the time zeroed in on a set of findings made by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, ESA's XMM-Newton and Hitomi, the Japanese-led X-ray telescope, according to a Daily Galaxy report.

If confirmed by follow-up research, this may make a major step forward in getting a grip on the puzzling notion of dark matter – "one of the biggest questions in science", said Joseph Conlon of Oxford University.

The work conducted by Oxford scientists shows that absorption of X-rays at an energy of 3.56 keV is detected when observing the region around the supermassive black hole at the centre of Perseus, which automatically suggests that dark matter particles in the cluster are simultaneously absorbing and emitting X-rays.

Such processes are well known to astronomers who study stars and clouds of gas with the help of optical telescopes. Light from a star enveloped by a cloud of gas frequently uncovers so-called absorption lines produced when starlight from some particular energy is absorbed by atoms in the gas cloud.

The absorption propels the atoms from a low to a high energy state, before they quickly drop back to the low energy levels with the emission of a certain amount of light. Yet, the light is re-emitted in all directions, producing a net loss of it at a specific energy level - something that is clearly seen in an absorption line in the star's observed spectrum.

By contrast, an observation of a cloud some distance away from the star would detect only the re-emitted, or fluorescent light at a specific energy, which would show up as an emission line.

The Oxford team suggests in their report that dark matter particles may be like atoms in having two energy states separated by 3.56 keV.

If so, it could be possible to observe an absorption line at 3.56 keV when observing at angles close to the direction of the black hole, and an emission line when looking at the cluster of hot gas at large angles away from the black hole.

"This is not a simple picture to paint, but it's possible that we've found a way to both explain the unusual X-ray signals coming from Perseus and uncover a hint about what dark matter actually is", stated co-author Nicholas Jennings.

Physicists have in recent years suggested new kinds of matter exist - ranging from planet-sized particles to enigmatic dark-matter life, The Daily Galaxy earlier reported, but so far none has been detected or its existence confirmed.

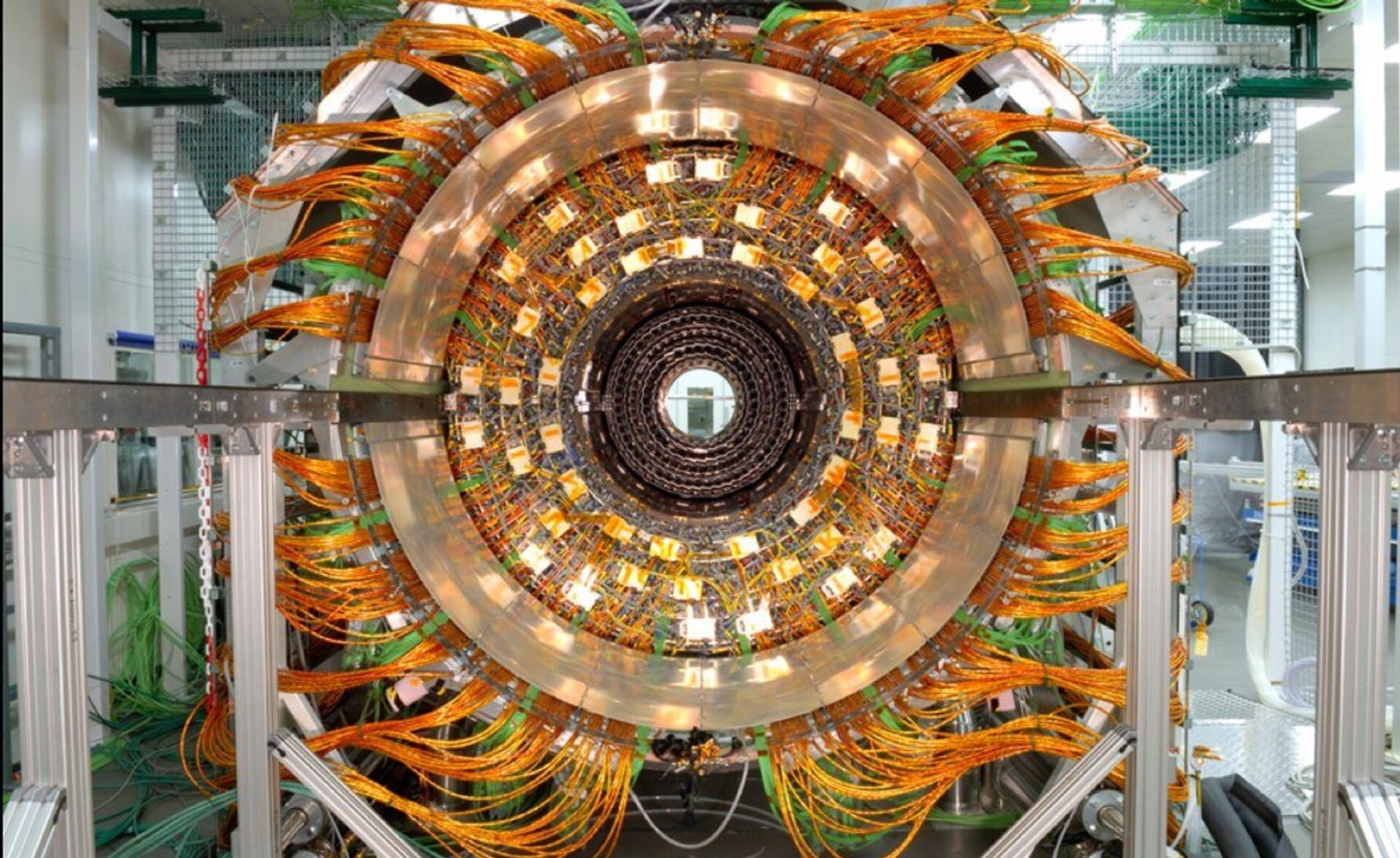

The Large Hadron Collider's discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012 prompted a bit of optimistic thinking and expectations of dark matter particles soon being discovered, but so far none has been confirmed.

"Inconveniently, dark matter is 'dark' in the sense that it hardly interacts with anything, particularly with light. Apparently, in some scenarios it could have a slight effect on light waves passing through. But other scenarios predict no interactions at all between our world and dark matter, other than those mediated by gravity. This would make its particles very hard to find", noted Sergey Troitsky, chief researcher at the Institute for Nuclear Research of the Russian Academy of Sciences in a 29 March 2019 post cited by The Daily Galaxy.

Yet, researchers believe they will learn more about the origins of dark matter when the ESA's Euclid satellite is launched in 2022, which aims at probing the eon before the Big Bang as well as explaining why the expansion of the universe is accelerating and what the source of this apparent acceleration is likely to be.