Chemical Analysis Reveals Why Stonehenge's Rocks Are Virtually Indestructible

03:01 GMT 17.08.2021 (Updated: 15:24 GMT 28.05.2023)

© AP Photo / Alastair Grant

Subscribe

A new study sheds light on how the world-famous megalithic Stonehenge monument in southern England has stood the test of time since it was built over the course of centuries starting more than 5,000 years ago.

The first extensive examination of samples obtained straight from one of Stonehenge's megaliths to uncover the geological and chemical structure of the stone was done by researchers from the University of Brighton, UK.

According to the findings published in PloS ONE magazine, the sarsens, the gigantic stones that make up the monument, are made out of sand-sized quartz grains glued tightly together by an interlocking "mosaic" of quartz crystals, researchers found out by using contemporary CT scanning, X-rays, microscopic analyses, and other techniques.

And these quartz grains are what make the stones "impervious to crumbling or erosion," according to the researchers.

"This small sample is probably the most analyzed piece of stone other than Moon rock," the head of the research Professor David Nash said in a statement.

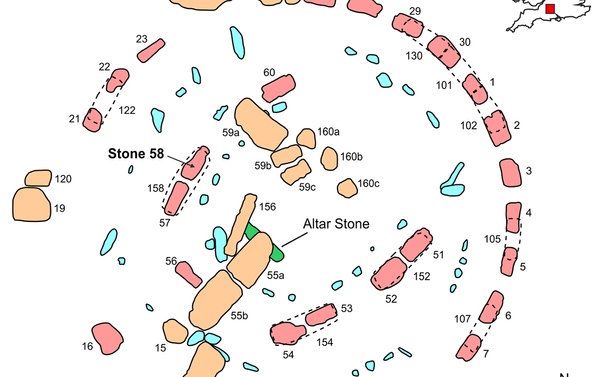

Fig 1. Plans of Stonehenge showing (A) the area of the monument enclosed by earthworks and (B) detail of the stone circle.

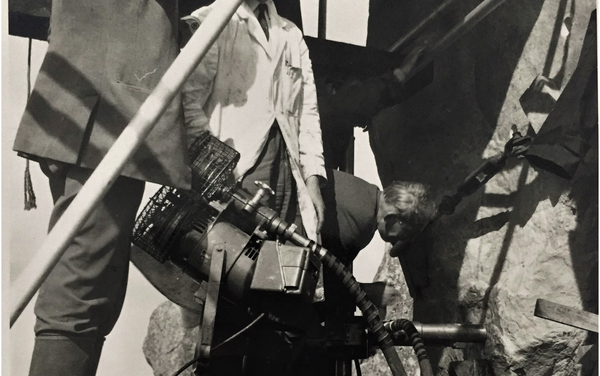

Drilling work on Stone 58 at Stonehenge by Van Moppes Ltd in August 1958, with Mr Robert Phillips pictured left.

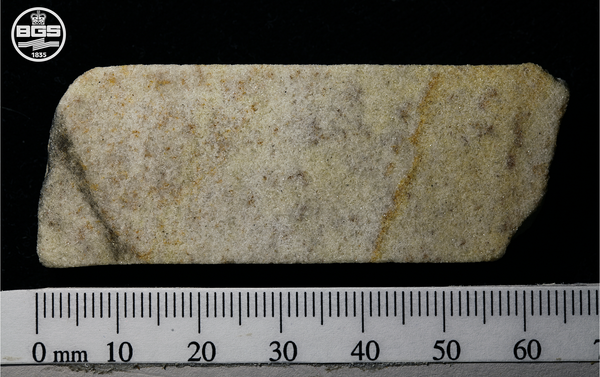

Image of section 2–3 of the Phillips’ Core from Stone 58 at Stonehenge.

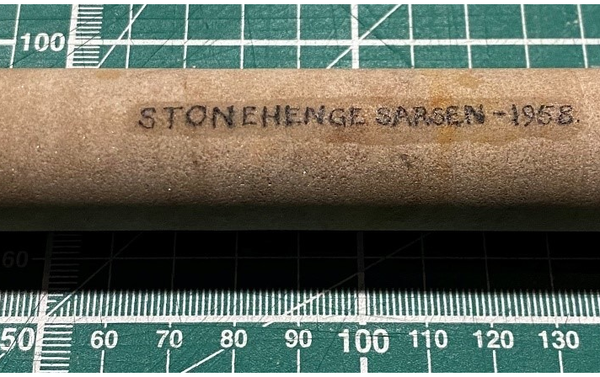

The Salisbury Museum Core from Stone 58 at Stonehenge.

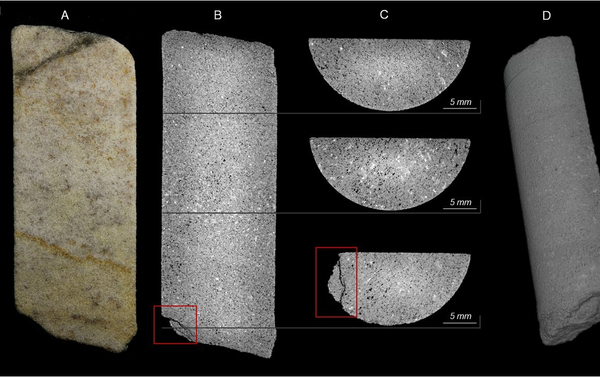

Optical (A) and Computed Tomography (B-C) images of section 2–3 of the Phillips’ Core from Stone 58 at Stonehenge.

Fig 1. Plans of Stonehenge showing (A) the area of the monument enclosed by earthworks and (B) detail of the stone circle.

Drilling work on Stone 58 at Stonehenge by Van Moppes Ltd in August 1958, with Mr Robert Phillips pictured left.

Image of section 2–3 of the Phillips’ Core from Stone 58 at Stonehenge.

The Salisbury Museum Core from Stone 58 at Stonehenge.

Optical (A) and Computed Tomography (B-C) images of section 2–3 of the Phillips’ Core from Stone 58 at Stonehenge.

According to the research team's statement upon publication, the sample occurred during a restoration project at Stonehenge in the 1950s, when a stonecutter named Robert Phillips was able to extract a 90 cm long (3 feet) cylindrical core sample from one of the stones.

Phillips transported the memento back to the US and kept it for decades, until he gave the material to researchers in 2018, just a few years before his death.

"It is extremely rare as a scientist you get the chance to work on samples of such national and international importance," Nash underlined. "Stonehenge is part of a World Heritage Site and is subject to the strictest legal protections, so it would be highly unlikely that we would be able to access this type of material today. Getting access to the core drilled from Stone 58 was very much the Holy Grail for our research."

According to the research conclusions, "no previous investigation has analyzed a single sarsen boulder with such a range of complementary techniques, meaning that comparisons with previous studies are limited to selected rock properties."

"Aside from being almost exclusively cemented by optically-continuous syntaxial quartz overgrowths, the petrography of Stone 58 is otherwise unremarkable compared to other sarsens. Likewise, the major element geochemistry of the stone is similar to the small number of chemical datasets available for sarsens," the research concludes.