Researchers Discover Way to Spot Uranium Cubes Meant for Nazi Nuke

16:02 GMT 27.08.2021 (Updated: 16:23 GMT 27.08.2021)

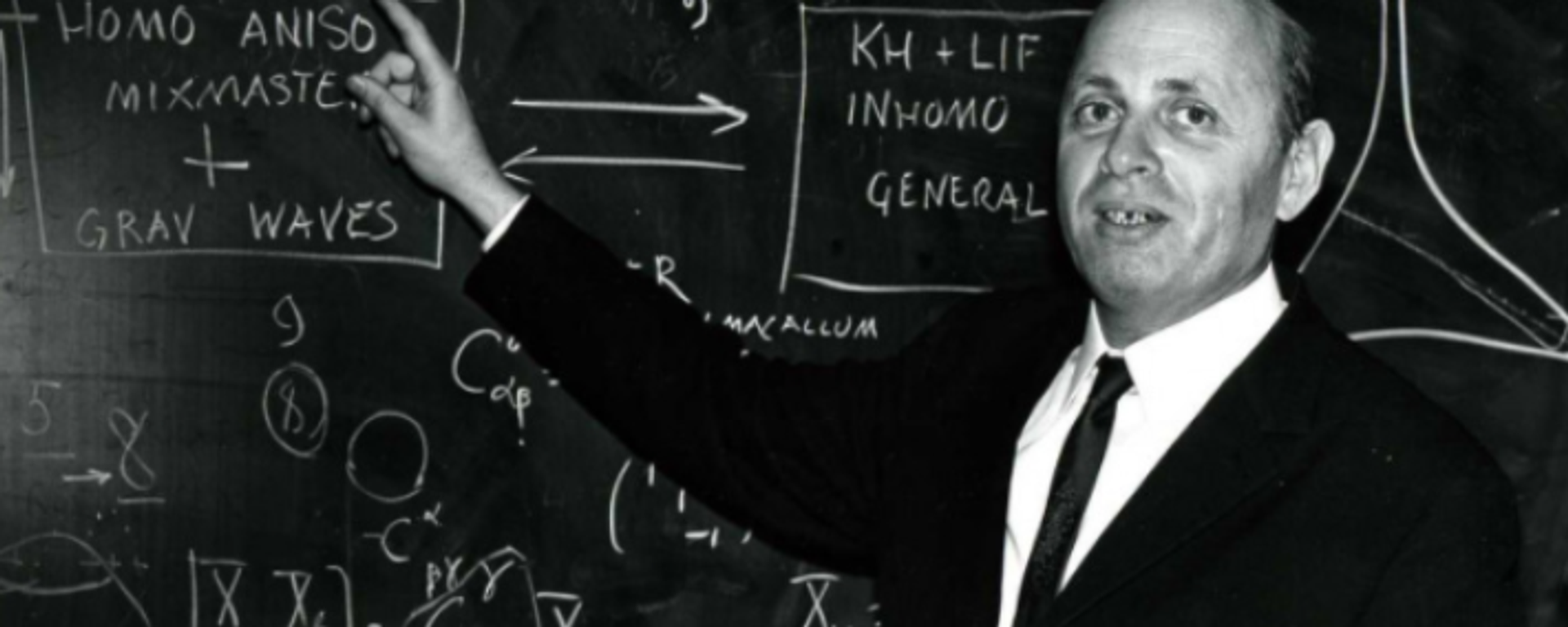

© Photo : John T. Consoli/University of Maryland

Subscribe

A plant in Oranienburg, northeastern Germany manufactured over 1,200 uranium oxide cubes during the Second World War – they were meant to be used in the construction of a Nazi German nuclear reactor, and eventually, help build a nuclear weapon. The US Air Force levelled the plant in March 1945 to prevent Soviet forces from capturing it intact.

Scientists from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) and University of Maryland have come up with a method they say may help detect and trace the origins of so-called "Heisenberg cubes" – uranium oxide cubes named after famed German nuclear physicist Werner Heisenberg and created for Nazi Germany's nuclear programme.

US forces seized over 650 Heisenberg cubes at the end of the Second World War after discovering them buried in a field near a medieval castle in the town of Haigerloch, southwestern Germany, where Nazi scientists were working on an experimental nuclear reactor.

Most of the charcoal grey, 2x2x2-inch 2.5 kg cubes were mysteriously lost after being shipped to the US, with hundreds believed to have been committed to the US nuclear programme, sent to research institutions, or stolen and sold to private collectors. Today, the fate of only about 12 of the uranium cubes is known.

Based on an analysis of material scrapped from a cube in PNNL’s possession, and in collaboration with a researcher at the University of Maryland who privately owns two more cubes, scientists have begun conducting nuclear forensic analysis they believe could help identify other missing cubes.

Their technique involves the use of radiochronometry, a method commonly used by geologists to determine the age of nuclear material based on its radioactive isotope content. In a press release, the scientists explained that when the cubes were first manufactured, they contained fairly pure uranium metal. With time, however, radioactive decay transformed the uranium into thorium and protactinium. Using radiochronometry to determine the uranium concentration effectively allows scientists to discover when the cubes were made, and, possibly, to determine any rare-earth element impurities which may be present, thereby revealing where the uranium used in the cubes was mined.

“We don’t know for a fact that the cubes are from the German programme, so first we want to establish that. Then we want to compare different cubes to see if we can classify them according to the particular research group that created them,” project principle researcher Jon Schwantes said.

Along with Heisenberg’s programme, nuclear physicist Kurt Diebner led a separate, second Nazi nuclear research programme, complete with its own experimental reactor, in the sleepy town of Gottow outside Berlin.

Along with determining the cubes’ authenticity, researchers hope their work can help determine which research team used them, since Heisenberg and Diebner used different coatings for the cubes to prevent them from oxidising. According to their press release, while the Heisenberg team used a cyanide-based coating, Diebner’s scientists used styrene. Some of the cubes from Diebner’s group were believed to have been sent to Heisenberg in Haigerloch as his team sought to collect enough fuel for the experimental reactor, which is why one of the University of Maryland cubes labelled as a Heisenberg cube was said to have used a styrene coating.

Brittany Robertson, a doctoral student working on the project along with Schwantes, told the American Chemical Society that while the research was fascinating, she was “glad [that] the Nazi programme wasn’t as advanced as they wanted it to be by the end of the war, because otherwise, the world would be a very different place.”

Dr. Schwantes said the work to uncover the origins of the Nazi uranium cubes should “enhance the capabilities of the nuclear forensic community in important ways.”

Nazi Nukes

By the end of the war in Europe, the Nazi German nuclear programme was nowhere near as far along in development as the US’s Manhattan Project, which carried out its first successful test of an atomic bomb in mid-July 1945. The US went on drop two nuclear bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, after the course of the war had already been determined.

Allied intelligence investigated the Nazi nuclear programme in April 1945, determining that the amount of fissile material the Nazis had was minuscule, and that German scientists had proven unsuccessful in enriching the material they had. Heisenberg and Diebner’s work with the cubes, which included attempts to incite uranium submerged in heavy water to create weapons-grade plutonium, proved a failure, in part due to an insufficient amount of uranium involved to trigger a sustained nuclear reaction.

Historians have blamed the failure of the Nazi nuclear programme on a number of factors, including its divisive nature, with scientists isolated into separate groups competing against one another instead of collaborating, like scientists working on the Manhattan Project or the Soviet atomic bomb project did. Others have pointed to the Nazi leadership’s decision to focus resources allocated to Nazi Wunderwaffe ("wonder weapon") projects on things like the V-series rockets, flying V aircraft and super-heavy tanks such as the impossibly impractical 1,000 tonne Landkreuzer P.1000 Ratte tank. The Nazis’ politicisation of science, including the decision to deport dozens of eminent nuclear scientists in the years before the war, also contributed to the failure of the nuclear bomb project, with many of these scientists settling in the US and the USSR and contributing to those two countries’ respective programmes instead.