US Pens Deal for New Military Base in Micronesia in Latest Move to Keep China Out of Pacific

© US Navy

Subscribe

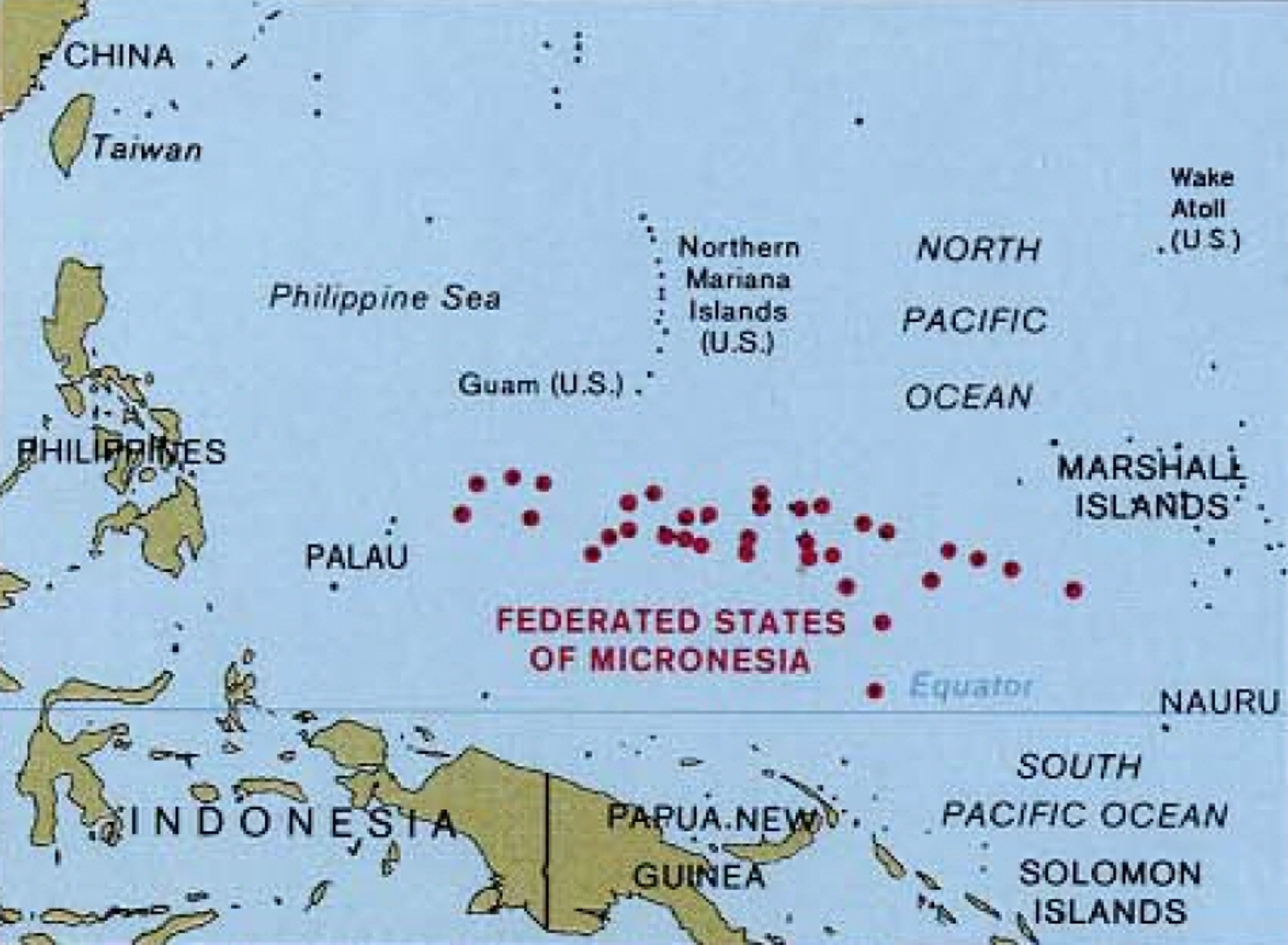

As the US pursues “great power competition” with China, Washington is on the hunt for new bases in the Pacific it can use to potentially get an upper hand in the fight. The latest site to be agreed upon is in the Federated States of Micronesia, a group of archipelagoes on the far side of the Philippine Sea from China.

Last month in Honolulu, Hawaii, Microensian President David Panuelo held high-level defense talks with US Navy Adm. John C. Aquilino, commander of US Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) about “the United States’ broader defense and force posture in the Pacific,” among other topics.

“The FSM and the United States collaborated on plans for more frequent and permanent US Armed Forces presence, and have agreed to cooperate on how that presence will be built up both temporarily and permanently within the FSM, with the purpose of serving the mutual security interests of both nations,” a news release by the Micronesian government noted.

The release gave no further details about where the base would be located or what type of facility it would be.

Speaking to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation after the summit, Panuelo said that while the small country of 58,000 people maintains diplomatic relations with China, he didn’t foresee the new US base as harming that relationship.

“The Freely Associated States are squarely part of the homeland, and so, we’re being protected by the United States,” he said, referring to a special client-state arrangement by which the FSM, as well as neighboring Palau and Republic of the Marshall Islands, get access to US federal aid in exchange for allowing the US military to operate in their territories and demand land for bases. The 20-year treaty is up for renewal in 2024.

“Any time there is a sudden change to the land, you affect our identity as Native islanders,” Sam Illesugam, a Micronesian native from the western Yap state, told Public Radio International last week. “This will alter the social landscape of our islands. Our islands are very, very small. Any type of changes to our lifestyle will greatly affect us.”

A ‘Power-Projection Superhighway’

The strategic position of Micronesia and neighboring Pacific islands has not gone unnoticed by US defense thinkers in recent years. In September 2019, a report by the Rand Corporation referred to the Freely Associated States as “a power-projection superhighway running through the heart of the North Pacific into Asia.”

"History underscores that the FAS play a vital role in US defense strategy," the report said, according to Radio New Zealand. "If ignored or subverted, they could become, as in the past, a critical vulnerability."

"Going forward, the United States, its allies, and its partners should demonstrate their commitment to the region by maintaining appropriate levels of funding to the FAS, and strengthening engagement with the FAS more broadly," Rand further advised.

More specific ideas appeared in an April 2021 op-ed in Defense One written by Abraham M. Denmark, who served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for East Asia under former US President Barack Obama from 2015 to 2017, and Eric Sayers, a visiting fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and former special assistant to INDOPACOM.

They argue that in order to deter the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the US must building facilities on “key Pacific islands” including Tinian, one of the Northern Mariana Islands north of Guam; Palau, which is about 750 miles southwest of Guam; and Yap, the westernmost large island in Micronesia, which sits about halfway between Guam and Palau.

Guam is presently the hub of US military activity in the region, with Pentagon facilities covering 29% of the island’s surface. Those include US Naval Base Guam, which is capable of docking aircraft carriers, and Andersen Air Force Base, a massive facility that houses strategic bombers and serves as a stopoff facility for aircraft crossing the Pacific.

The US military’s presence on Guam is widely reviled, as massive air, water and noise pollution affect much of the island and the steadily encroaching US military facilities cut down more and more forestland, endangering the livelihoods of the native Chamorro people and sparking protests.

Fears of Chinese Expansion Fall Flat

In recent years, the PLA Navy has increased its activities in the Philippine Sea, including drilling with its new aircraft carriers, as well as with long-range aircraft. The sea encloses Taiwan’s eastern flank and is necessary to sail through if one wishes to avoid an inherently contentious transit through the Taiwan Strait. It has also tested new long-range missiles, like the Dong Feng-26, that are capable of reaching Guam from the Chinese mainland 2,000 miles away.

US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin told the US Senate Armed Services Committee in June as he argued for a larger military budget that China "wants to control the Indo-Pacific" region as part of its quest to become the "preeminent country" on the planet.

A map of the western Pacific, highlighting the Federated States of Micronesia

Further, the inclusion or potential inclusion of several Pacific Island nations into China’s Belt and Road Initiative has aroused fears in the US and Australia that China is trying to expand its sphere of influence in the region and could even base military forces there.

In 2018, the Solomon Islands switched its recognition of the Chinese government from Taipei to Beijing, and Australian and Western media began to fret that Chinese military facilities would soon follow. As Sputnik reported at the time, those fears were heavily based on false reports that China had been scouting a spot in the nearby island nation of Vanuatu for a new naval base location - negotiations which instead turned out to be a $190 million commercial wharf on Vanuatu’s Santo Island.

The following year Kiribati switched its recognition, as well, and the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), a Canberra-based think tank funded in part by the Australian Department of Defense, began raising its own fears of Chinese development, claiming Beijing would imminently begin seafloor dredging projects to widen the nation’s narrow islands and fortify them with military bases, as it has done to some South China Sea islands.

ASPI accused China of “moving to achieve control over the vital trans-Pacific sea lines of communication under the guise of assisting with economic development and climate-change adaptation,” referring to a deal in January of that year for Beijing to support Kiribati’s 20-year development plan aimed at saving the island nation from seas rising due to climate change.

A repaired derelict airfield on the remote island of Canton was served up as proof in May 2021 that the Chinese were planning to turn it into a new air base, although Beijing soon clarified the repairs were for civilian use, as the island had once been a tourist hub.