As EU Pours Money Into Libya to Tackle Migration, is Bloc Ignoring Human Rights Abuses?

19:19 GMT 20.12.2021 (Updated: 17:14 GMT 12.04.2023)

© AP Photo / Olmo Calvo

Subscribe

Longread

The European Commission is providing new P150 class patrol boats to the Libyan Coast Guard to stop people trafficking. But does the EU's realpolitik on stopping the flow of migrants contradict their stated aim of guarding human rights?

The European Union is pouring hundreds of millions of euros into Libya in an attempt to stem the flow of migrants heading across the Mediterranean to Italy and Malta.

Yasha Maccanico, a researcher at Statewatch, said the EU “was over-ambitious” in trying to stop irregular migration by economic migrants altogether.

He said: “If the average earnings in my country are higher than those in another country, the whole of that country is going to want to come to mine. And it's that crude.”

Why are Migrants Going Through Libya?

Libya has become one of the most popular jumping-off points for migrants coming to Europe.

The United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR, said the most common nationality of the migrants in Libya was Sudanese (17 percent), followed by people from Mali (11 percent), Niger and Chad but many come from Eritrea and Ethiopia and more than one in 10 are from Bangladesh and will have followed a tortuous route to get to north Africa in the first place.

In the period of 12 - 18 December, 466 migrants were rescued/intercepted at sea and returned to Libya.

— IOM Libya (@IOM_Libya) December 20, 2021

👇IOM Libya's Maritime Update👇 pic.twitter.com/jqHZOErior

While some of them are refugees fleeing conflict and political persecution in their home country, it would appear the majority are economic migrants hoping for a better life.

Although Morocco is slightly closer to the European mainland, it is Libya which most of the people trafficking gangs choose to use as their conduit to Europe, because the rule of law is weak and corruption is rife.

The International Organisation for Migration said 44,000 people had reached Europe illegally in the first nine months of this year crossing by sea from Libya or Tunisia.

Outsourcing Sea Border Control to Libyans

More than 23,000 migrants have been sent back to Libya this year by the EU’s border control agency, Frontex, and at least 1,100 have drowned in the Mediterranean, although the figure may be much higher.

Earlier this year it was announced Brussels would be funding three new patrol boats for the Libyan coastguard.

Although they are described as “search-and-rescue vessels” they are designed to intercept people trafficking boats and dinghies at sea and return them to Libya.

Migrants aboard the Open Arms aid boat, of Proactiva Open Arms Spanish NGO, react as the ship approaches the port of Barcelona, Spain, Wednesday, July 4, 2018. The aid boat sailed to Spain with 60 migrants rescued on Saturday in waters near Libya, after it was rejected by both Italy and Malta

© AP Photo / Olmo Calvo

Libya has received more than 455 million euros from the EU, through the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, and last year it received 30 vehicles from the Italian Interior Ministry to assist the Coastguard patrolling the beaches and preventing migrant boats setting out to sea.

Dr Danai Angeli, a human rights lawyer specialising in asylum and migration policy, said European states have increasingly sought to manage migration by keeping migrants as far as possible away from their borders and setting up agreements with third countries such as Libya and Turkey to accept the migrants, effectively outsourcing the problem.

‘Politically Unsustainable’ Strategy?

He said: “By keeping migrants at a geographical distance, European states seek to escape the human rights obligations owed to refugees and migrants attempting to cross a state’s territory. This strategy is both legally and politically unsustainable.”

When you see @EU_Commission talking about protecting migrant rights on #InternationalMigrantsDay, remember that the E.U. continues to facilitate the enslavement of migrants in Libya.

— Freedom United (@freedomunitedHQ) December 14, 2021

Sign the petition to tell them #ActionsSpeakLouder https://t.co/7ljbD2kaf0 pic.twitter.com/IQff8YStoJ

Metin Çorabatir, President of the Ankara-based Research Centre on Asylum and Migration and a former UNHCR spokesman in Turkey, said Libya was not a unique case but was part of a general trend.

He said EU countries were increasingly implementing restrictive policies and added: "They are trying to keep, as much as possible, the refugees and migrants out of the EU territory. This externalisation of asylum is a common trend.”

Part of the blame lay at the door of the UN and the UNHCR, he said.

Dr Çorabatir said: “Instead of defending openly the rights of refugees, they are moving to emphasise the importance of keeping good relations with the governments. They are becoming shyer and less outspoken about the rights of refugees.”

On being returned to Libya most of the migrants end up in detention centres where conditions are appalling.

What are Conditions Like in Libyan Camps?

A recent report by the UN’s Independent Fact-Finding Mission on Libya said conditions in migrant detention centres there represented a possible crime against humanity.

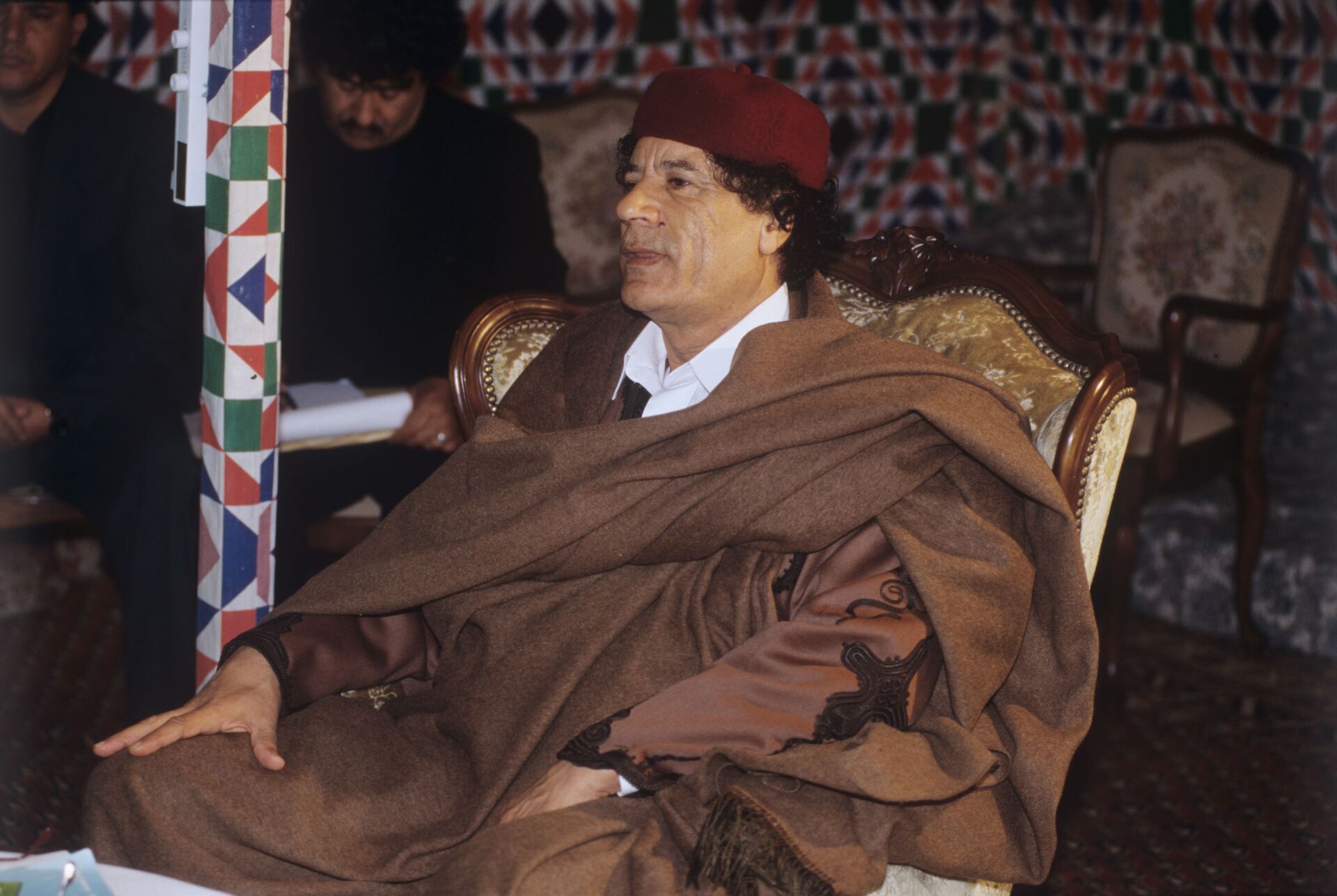

Muammar al-Gaddafi, leader of Libya accorded the honorifics "Guide of the First of September Great Revolution of the Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya".

© Sputnik / Vladimir Fedorenko

/ The report said: “Since the fall of the Gaddafi regime in 2011, the fragmentation of the state and the proliferation of weapons and of militias vying for control of territory and resources has severely undermined the rule of law in Libya.”

They go on to say: “Reports indicate that the human rights situation of migrants, asylum seekers and refugees in Libya has deteriorated since 2016.”and “from the moment that migrants enter Libya destined for Europe, they are systematically subjected to a litany of abuses.”

Don't send migrants back to unsafe countries, pope says, citing "concentration camp" conditions in Libya. https://t.co/ko0fnNYaT0 pic.twitter.com/sBcDjP3Ozs

— Philip Pullella (@PhilipPullella) October 24, 2021

The Independent Fact-Finding Mission report said while in camps run by the Department for Combating Illegal Migration (DCIM) they face “intolerable conditions calculated to cause suffering” and will often pay large sums of money to people traffickers who “have links to the state”in order to escape and get on board a Europe-bound boat.

Migrants who had been held in DCIM camps told the UN team of the “harsh conditions” and said children were often detained alongside adults, placing them at high risk of abuse.

“Torture (such as electric shocks) and sexual violence (including rape and forced prostitution) are prevalent,” said the report.

It went on to say: “Migrants are detained for indefinite periods without an opportunity to have the legality of their detention reviewed, and the only practicable means of escape is by paying large sums of money to the guards or engaging in forced labour or sexual favours inside or outside the detention centre for the benefit of private individuals.”

Glimpse Behind the Barbed Wire

The UN fact-finding team said it had been unable to gain access to the DCIM camps but journalist Ian Urbina visited one of the secret migrant prisons in the Tripoli suburb of Ghout al-Shaal.

He said 1,800 migrants were housed in a former cement storage depot, which was now surrounded by walls, topped by barbed wire and guards with Kalashnikovs.

Urbina wrote, in an article for The New Yorker: “The prison is controlled by a militia which euphemistically calls itself the Public Security Agency.”

An inmate at the camp, Aliou Cande, told Urbina there was one toilet for every 100 people and migrants would often defecate in the shower.

Cande told the journalist there were no beds and inmates had to share flimsy floor mats, the food was dreadful and guards would beat migrants for the smallest of infractions of the rules.

Guards reportedly offered to get migrants out of the camp for 2,500 dinars (US$500) and used their cellphones to call relatives of the inmates to get the money in advance.

Libya’s former Justice Minister, Salah Marghani, told Urbina: “The EU did something they carefully considered and planned for many years. Create a hellhole in Libya, with the idea of deterring people from entering Europe.”

‘Libya is Not Safe for Migrants’

Mr Çorabatir said: “What we have been witnessing in Libya is terrible. Libya is not a secure country, not a safe country for not only migrants and refugees, but for many other people. Keeping these people in such conditions is against human rights and international refugee law.”

Mr Maccanico, who is an associate at the University of Bristol School for Policy Studies, agreed: “It's ridiculous to pretend that Libya is a safe country for migrants. It's absurd that Libya has been assigned as a search and rescue area. The Libyan Coast Guard are basically behaving like cowboys, and they're intimidating civilian search-and-rescue vessels.”

He said the Libyan Coast Guard has reportedly been infiltrated by people traffickers.

It has been claimed that in November 2017 the Libyan Coastguard hindered an attempted rescue in the Mediterranean by the NGO Sea-Watch, leading to the deaths of at least five migrants by drowning.

As for the camps the migrants were returned to, Mr Maccanico said: “The conditions in Libyan detention centres were already a problem under Gaddafi, but they've got a lot worse. Italian courts are full of testimonies of the violence that has been going on in Libyan centres. Journalists, survivors and lawyers who I've spoken to have told me some horrible stuff. I mean, from young girls being raped and their children being taken away from them. It's awful.”

Libyan Promise to End Torture

On Sunday, 12 December, Libya’s Justice Minister Halima Abdurrahman said they intended to end all forms of torture inside detention centres but the promise was greeted with cynicism from many who know the weakness of the Libyan government.

Dr Angeli said: “States are responsible for the effects of their actions even when the harm occurs outside their territories. Europe cannot selectively condemn some human rights violations, and turn a blind eye to others."

European states should try and create a comprehensive and long-term strategy to manage inward migration, she said.

Mr Çorabatir said after the Second World War the Geneva Convention was set up to define the status of refugees and how they should be treated.

But he said: “The nature of the refugee problem is international. So the solutions should be sought internationally. What we have been witnessing increasingly is that unfortunately each country is trying to find their own restrictive policies and moving away from the international principles and international co-operation.”

Spanish humanitarian Rescue Ship Open Arms off the Sicilian Island of Lampedusa

© AP Photo / Salvatore Cavalli

The Norwegian Refugee Council said part of the problem is that some wealthy countries are shirking their responsibility to take in refugees - Japan has only taken in 1,394 in the last decade.

The trouble is that most refugees from Africa and Middle East still want to go to Europe, where they are more likely to have family and compatriots, rather than Japan.

"Freedom is decision is the inalienable right of the refugee himself," said Dr Gerrit Jane van Heuven Goedhart, the then UN High Commissioner for Refugees in 1955.

Amnesty International has outlined an eight-point plan to “solve the migrant crisis” which includes opening up “safe routes for sanctuary” to refugees and taking stronger action to investigate and prosecution people trafficking gangs.