EU Needs 10-15 Years To Replace Russian Gas With African Hydrocarbons, Energy Experts Say

11:30 GMT 06.05.2022 (Updated: 11:44 GMT 09.02.2023)

© AP Photo / CHRISTINE NESBITT

Subscribe

Having introduced sweeping sanctions against Russian energy suppliers, the European Union (EU) is trying to curry favour with African hydrocarbon producers to reduce its dependence on Moscow by almost two-thirds this year, Bloomberg reports. The EU sees Western and Northern African states as potential alternative gas suppliers.

"The European Union (EU) is clutching at straws," says Dr Mamdouh G. Salameh, an international oil economist and visiting professor of energy economics at the ESCP Europe Business School in London. "[The bloc's] efforts to diversify its gas needs away from Russia is a painstaking job that will take years to accomplish if ever."

The EU's turn to Africa comes as no surprise given the latter’s vast energy resources. According to some estimates, Nigeria has proven gas deposits of 206.53 trillion cubic feet (cu ft); Algeria, ranking second in Africa, is sitting on approximately 159.1 trillion cu ft; and Senegal has 120 trillion cu ft, amongst others. However, observers indicate that the major obstacle in tapping these vast energy reserves is overcoming underdeveloped infrastructure.

"The two relatively significant African Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) exporters are Algeria - currently exporting 29.3 million tonnes (mt) - and Nigeria - with an export capacity of 22.2 mt," says Salameh. "The rest of Africa’s producers have limited production and export capacities with neither LNG plants nor gas pipelines."

Expanding LNG capacity is capital intensive and time consuming, according to Dr Gal Luft, co-director of the US-based Institute for the Analysis of Global Security.

"The only realistic solution I can foresee is shipping gas in compressed form (CNG) rather than liquefied form (LNG)," says the scholar. "This can be done with existing technologies by compressing the gas in dedicated vessels and discharging it on the receiving side. This approach spares the need to build liquefaction and regasification facilities. But here too, while the technology already exists, it will take time to build the dedicated tankers. It is also unclear that North Africa has the ability to ramp up gas supply in the near term. This will require significant investment and there is no plan who will invest."

When it comes to African pipeline projects, it's hard to judge how long this might take, he also notes.

Location of Trans-Saharan gas pipeline

Trans-Saharan Pipeline

In mid-February 2022, Niger, Algeria and Nigeria inked an agreement that looks to revive work on the $13 billion Trans-Saharan Gas Pipeline project, also known as the NIGAL pipeline or the Trans-African Gas Pipeline.

The 4,128 km-long (2,565 miles) pipeline looks to link Warri in Nigeria to Hassi R'Mel in Algeria, passing through Niger and carrying 30 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas to European markets every year via Algeria’s strategic Mediterranean coast. In comparison, Russia's Nord Stream and Nord Stream 2 pipelines would have delivered a total of 110 bcm to Europe over the same time period.

However, as Salameh points out, “The Trans-Saharan pipeline […] is still at the drawing board stage", adding that it is unlikely that "it will see the light of day in even the next 10 years."

The NIGAL pipeline project was first conceived in 1970, while on 14 January, 2002 a Memorandum of Understanding was signed by Nigeria’s National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) and Sonatrach, Algeria’s state-owned oil company, to prepare this project.

In 2009, both parties agreed to proceed, but NATO’s 2011 bombing of Libya and subsequent collapse of the state, as well as the bloody Aménas hostage crisis of 2013, scared off potential investors. Nigeria, Niger and Algeria are among the least secure areas in West Africa due to active terrorist movements destabilising them.

Nigeria-Morocco offshore gas pipeline project

© Photo : The Africa Report/screenshot

Nigeria-Morocco Pipeline

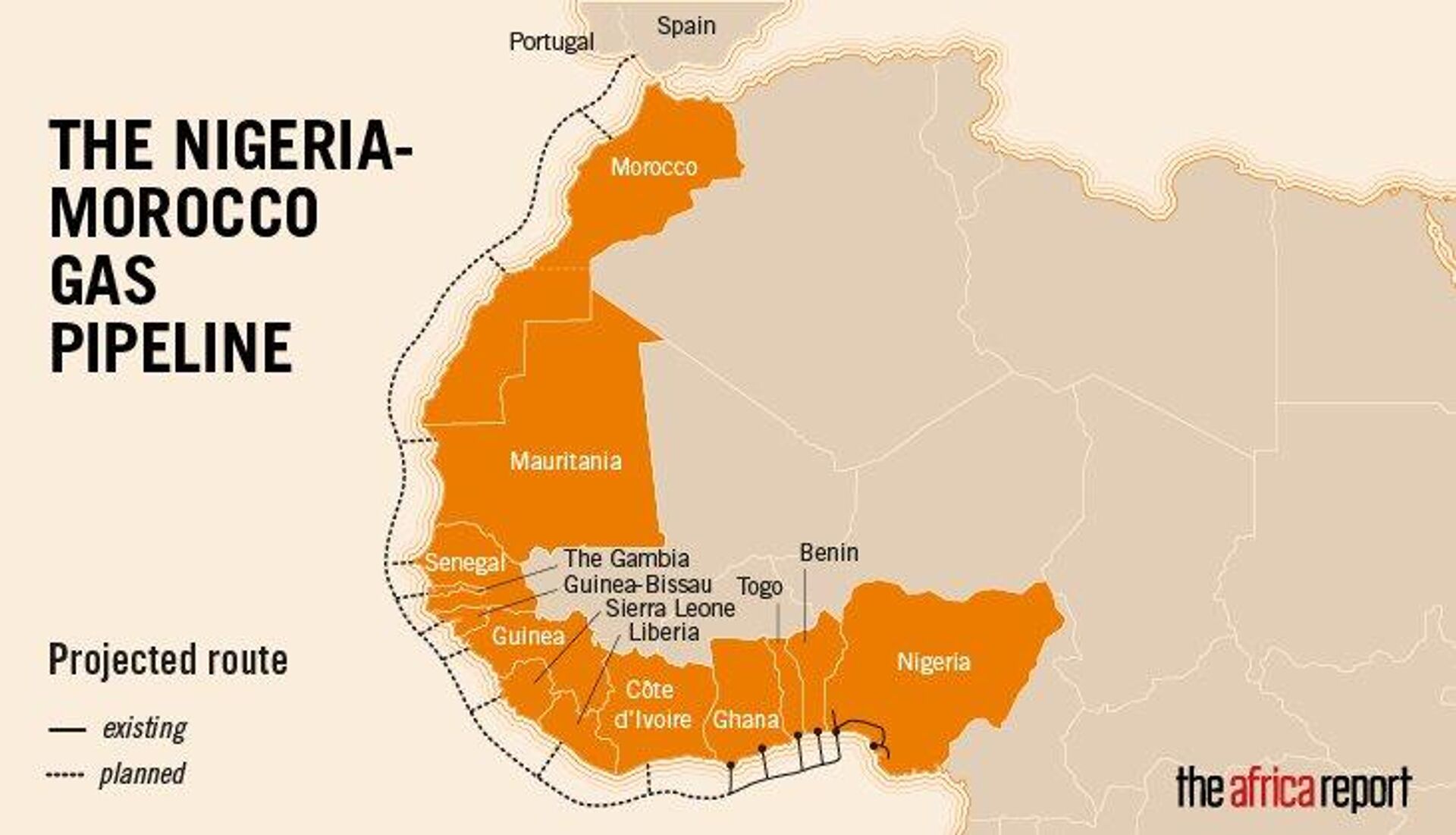

A competing Nigeria-Morocco gas pipeline project has likewise been on the cards since 2016. The project envisages the construction of a 5,660 km-long (3,517 mi) offshore pipeline – the second-longest in the world – to carry gas from Nigeria to Morocco through eleven West African nations.

Besides linking Nigeria and Morocco, it is expected to connect African gas reserves to Europe, as Nigeria's minister for petroleum resources, Timipre Sylva, told reporters in Abuja on Monday. Sylva noted that Russia and some other world energy producers are interested in investing in the project, which may kick off before May 2023. However, it's not known how much the project will cost, nor how long it will take to finish.

There are also a number of less ambitious gas pipeline projects which are at different stages of planning or construction in West, East and South Africa. However, many of them remain unfinished due to a lack of investments, criminal attacks, a dire security situation, and political divisions within the continent.

"Engineering challenges aside, political issues having to do with rivalries between the various countries involved in Western Sahara, the rampant terrorist activity in some of the territories and the difficulty in protecting such pipeline infrastructure both on land and under the sea are making this solution extremely difficult to execute," says Luft.

Currently, the EU may start reducing its dependence on Russia gradually over a period of 10-15 years, and then, possibly, the African continent could provide Europe with a worthy alternative, Salameh explains.

"EU Cannot Replace Russian Gas in Foreseeable Future"

Since the beginning of Russia's special operation to de-militarise and de-Nazify Ukraine, EU officials have introduced several rounds of sanctions against Moscow, as well as pledging to dramatically reduce the 27-nation bloc's dependence on Russian oil, gas and coal. In early March, the EU announced plans to slash its dependence on Russian gas by two-thirds during 2022. Europe gets about 40% of its natural gas from Russia.

The EU is urgently seeking alternatives to substitute Russia's hydrocarbons. Given the delays in firming up African gas suppliers, the bloc is looking to sure up an agreement with the US to deliver 15 billion cubic metres (bcm) of additional liquefied fuel in 2022, and a further 50 billion cubic metres (bcm) a year until 2030, according to Bloomberg.

Brussels is also considering signing a trilateral memorandum of understanding with Egypt and Israel to increase LNG supplies to the Old Continent by the summer of 2022. Plans to double the Southern Gas Corridor’s capacity, which brings up to 20 bcm annually from Azerbaijan, is also on the table, as well as LNG deliveries from Canada, Japan and South Korea, according to the media outlet. The EU has urged member nations to ensure "open, flexible, liquid and well-functioning global LNG markets," both with major LNG producers, including the US, Australia and Qatar, and consumers, including China, Japan and South Korea.

However, Salameh argues that it appears unlikely that major LNG producers will be capable of quickly filling Russia's shoes in the wake of the EU energy embargo. “The [EU] will never be able to replace Russian gas supplies now or in the foreseeable future," the professor stresses.

Salameh notes that the combined total LNG exports of the United States, Qatar and Australia could barely replace current Russian gas supplies to the EU. He explains that this situation partly stems from the fact that the bulk of US, Qatari and Australian LNG exports are bought years in advance by customers in the Asia-Pacific region; and partly because the EU has limited LNG import capacity in terms of LNG terminals and storage spaces.

In short, the EU appears to be shooting itself in the foot by abruptly severing energy ties with Russia, as it may take up to a decade for the bloc to build enough infrastructure to satisfy its needs, concludes the economist.