Scientists Discover Earth's Earliest Major Wildfire Dating Some 430 Million Years Ago

© Wikipedia / John McColgan

Subscribe

Plant life would have relied substantially on water to reproduce some 443 to 419 million years ago (Mya), and would have been unlikely to appear in areas that were dry for part or all of the year. The discussed wildfires would have burnt through fairly short vegetation, with the occasional knee- or waist-high plant thrown in for good measure.

Scientists have discovered the world's oldest wildfires thanks to 430-million-year-old charcoal deposits discovered in Wales and Poland, providing invaluable information on life on Earth during the Silurian period of the Paleozoic era, a new research published in the journal Geology said.

The team noted in the study that during that geological period the ancient fungus Prototaxites would have dominated the environment rather than trees we all know today. The fungus' exact size is unknown, however it is said to have grown to a height of nine meters (almost 30 feet).

According to the Geological Society of America's news release upon the publication, Ian Glasspool of Colby College in Maine, a lead author of the study, said that the discovered evidence of wildfire suggests that it is the earliest one ever found.

"Wildfire has been an integral component in earth-system processes for a long time and its role in those processes has almost certainly been underemphasized,” the researcher said. "It looks now as though our evidence of fire coincides closely with our evidence of the earliest land plant macrofossils. So as soon as there's fuel, at least in the form of plant macrofossils, there is wildfire pretty much instantly."

Indeed, the researchers noted that wildfires require fuel, namely plants, an ignition source, such as lightning strikes, and enough oxygen to burn to survive long enough to cause damage to the ecosystem.

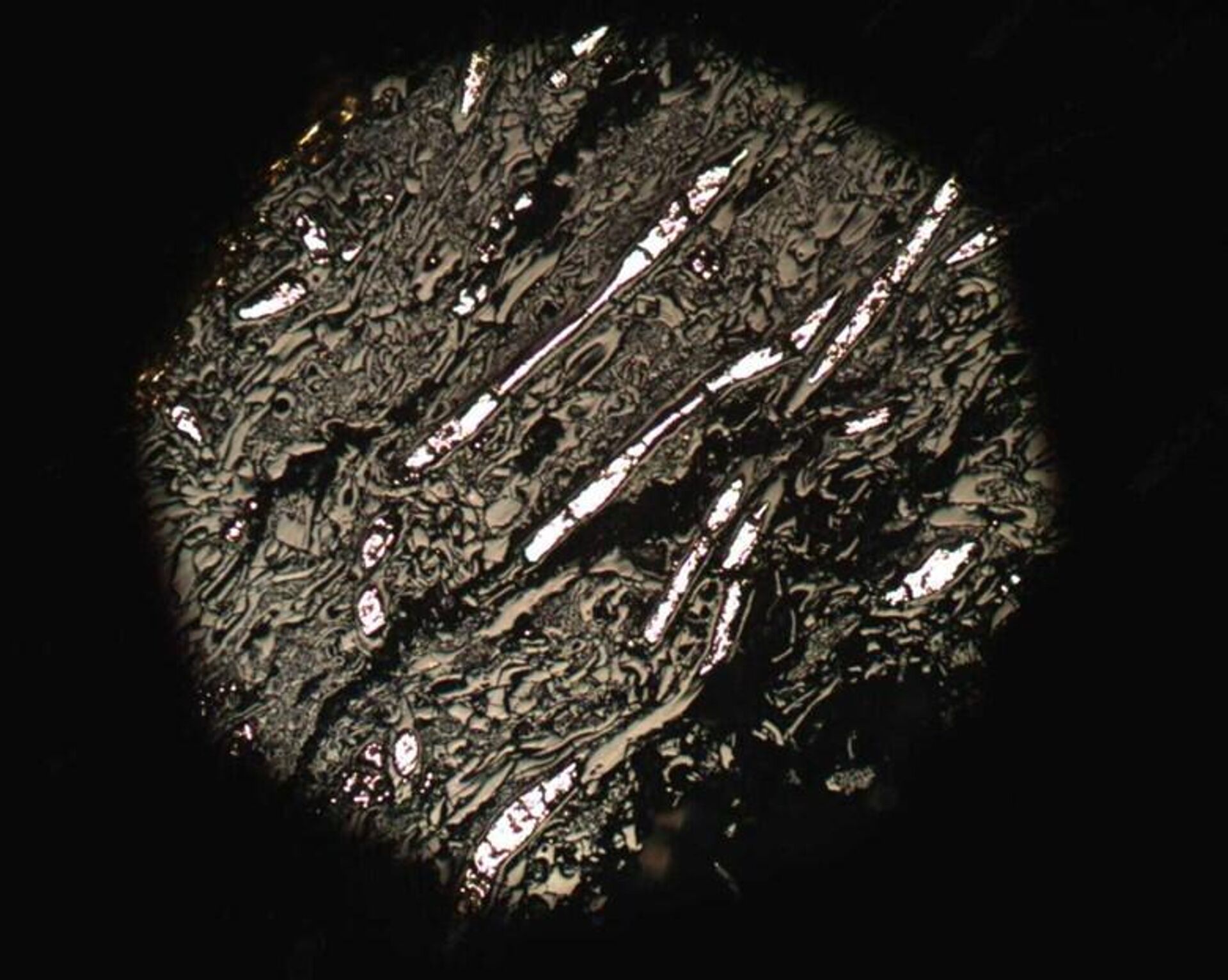

Reflected light microscope image of a 430-million-year-old charred Prototaxites from a borehole drilled in Wales. The high-reflecting (white) material infilling the larger tubes is pyrite, a mineral commonly found in association with charcoal.

© Photo : GSA / Ian Glasspool

The study further suggested that the ability of the fires to spread and leave charcoal deposits indicates Earth's atmospheric oxygen levels were at least 16%. That percentage is currently at 21%, but it has fluctuated drastically throughout Earth's 4.5-billion-year history. According to the findings, atmospheric oxygen levels 430 million years ago may have been as high as 21% or perhaps higher.

Increased plant life and photosynthesis would have theoretically contributed more to the oxygen cycle around the time of the wildfires, and understanding the specifics of that oxygen cycle across time offers scientists a clearer sense of how life would have developed.

"The Silurian landscape had to have enough vegetation across it to have wildfires propagated and to leave a record of that wildfire," research author Robert Gastaldo said. "At points in time that we're sampling windows of, there was enough biomass around to be able to provide us with a record of wildfire that we can identify and use to pinpoint the vegetation and process in time."

The geography of what is now Europe looked very different hundreds of millions of years ago, and the two sites researchers studied would have been on the old Avalonia and Baltica continents during the time these wildfires were raging.

Wildfires would have played an important role in carbon and phosphorus cycles, as well as the movement of sediment on the Earth's surface, both then and now, according to the findings.

The new discovery of ancient wildfires reportedly breaks the previous record for the oldest wildfire on geological record by 10 million years, and it also emphasizes the importance of wildfire study in chronicling Earth's history.

All in all, the authors determined that atmospheric oxygen levels during the Silurian were comparable to, or possibly higher than, those of today, based on the charcoal which was studied.

Increased photosynthesis from terrestrial plant life would have impacted the oxygen cycle, raising oxygen levels to near current levels. As a result, wildfires would have been a major global phenomenon during the Silurian, influencing sediment movement and carbon and phosphorus cycling.