https://sputnikglobe.com/20220630/in-depth-narcotics-experience-mckinsey-advised-us-pharmas-on-how-to-turbo-sell-opioids--1096843413.html

'In-Depth Narcotics Experience': McKinsey Advised US Pharmas on How to Turbo Sell Opioids

'In-Depth Narcotics Experience': McKinsey Advised US Pharmas on How to Turbo Sell Opioids

Sputnik International

The US opioid crisis started at the end of the 1990s after doctors began prescribing opioid-based painkillers even in cases of non-severe pain. They were... 30.06.2022, Sputnik International

2022-06-30T18:46+0000

2022-06-30T18:46+0000

2022-06-30T18:53+0000

us

opioid crisis

us opioid crisis

drugs

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/101850/59/1018505995_0:124:3000:1812_1920x0_80_0_0_3320bde210bdf8cefc5676abca0c19d2.jpg

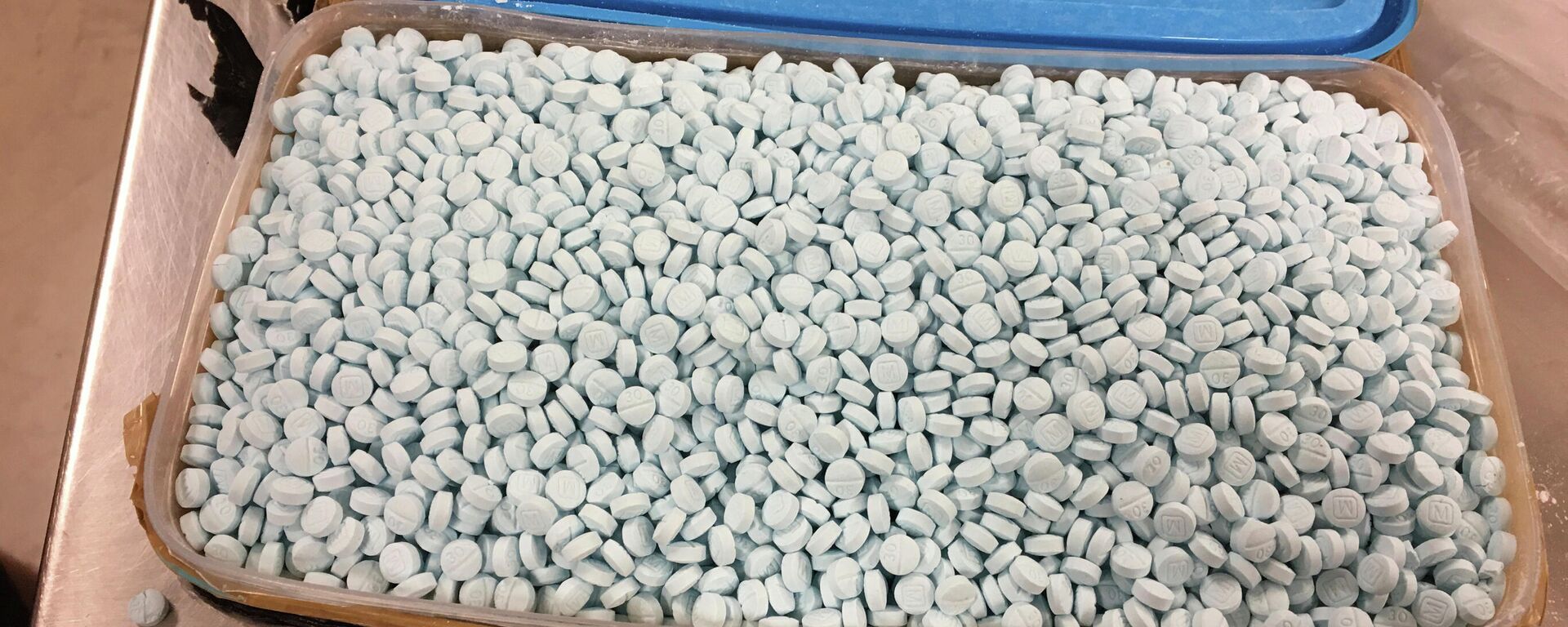

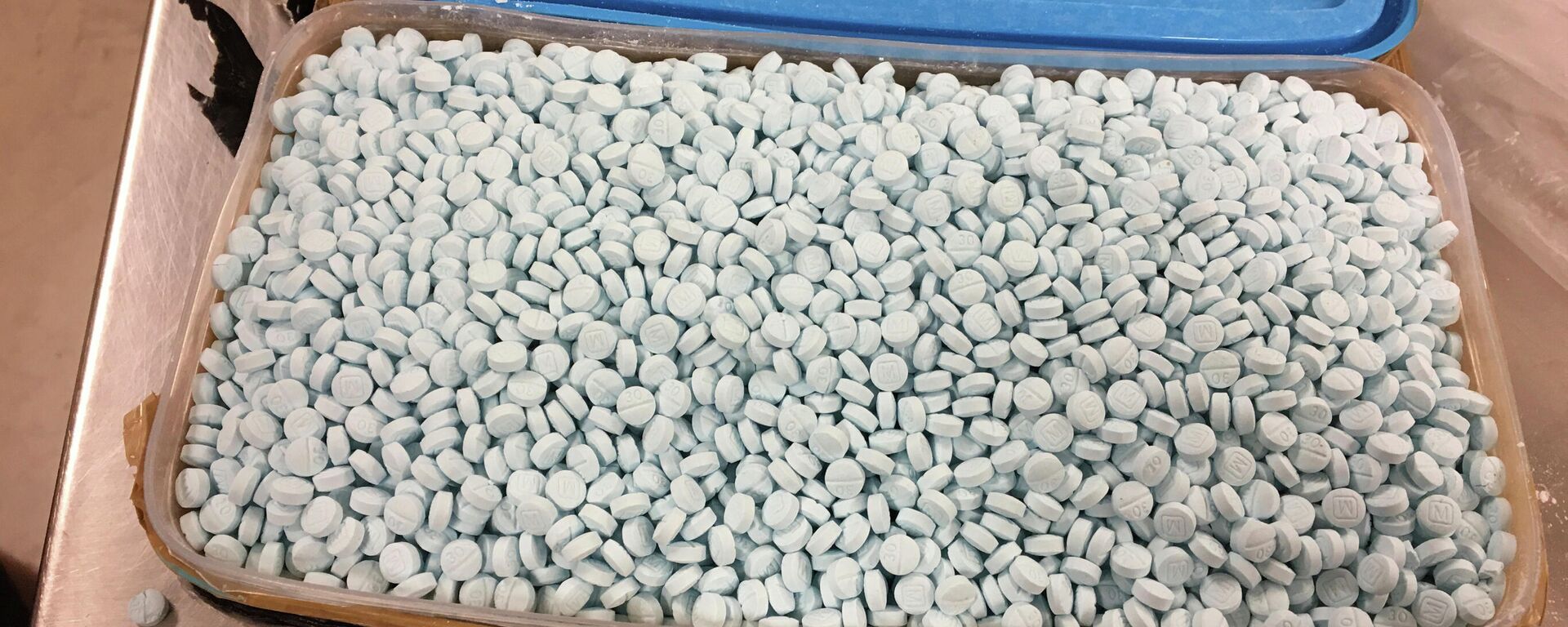

Global consulting giant McKinsey & Company advised several painkillers producers for 15 years on how to "turbocharge" prescription drug sales largely to blame for starting the opioid epidemic in the US, The New York Times has revealed citing over 100,000 documents.The docs emerged as a part of a settlement deal that McKinsey signed with several state attorneys that sued the company.Apart from working with Endo, Purdue, and Mallinckrodt, the company also provided "in-depth experience in narcotics" for Johnson & Johnson subsidiaries producing controlled substances. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of US citizens died from overdose, often linked to these very drugs.How It All StartedAccording to the disclosed documents, McKinsey helped both Endo and Purdue, the creators of two of the most widespread opioid-based drugs for severe chronic pain, to launch their products Opana and OxyContin in 2006-2008. The firm even advised one of the companies on how to overcome a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) block which it had encountered in 2008.The FDA blocked Purdue's attempt to release an upgraded version of its OxyContin, which was more difficult to snort or dilute and inject in bloodstream – two methods of the prescription drug's abuse that already had been devised by some of its recipients. In order to help Purdue get the license, McKinsey interviewed an ex-drug dealer on the medication's abuse, prepared docs and even coached the drug firm's officials for meetings with the FDA as the pharmaceutical company knew its drug had been widely abused, the docs suggest.Purdue's main competitor, Endo, also released a new version of its painkiller and tried to get it marked as resistant to crushing (for snorting) and diluting (for injections), but the FDA did not allow the latter citing lack of such properties. Nonetheless, the drug's release was a success and coincided with a drop in abuse-resistant OxyContin's sales.This came, however, at a cost of local epidemics of previously unseen blood disorders in several US states in 2012 – patients were found to be anemic and suffered from kidney failure. Many of them admitted to abusing updated Opana – the new formulae indeed discouraged from snorting it, but still allowed injection abuse. However, the same component that prevented crushing took a great toll on those who tried to inject the drug to get a better high, leading to red blood cells' destruction and organ damage.Going on the 'Offensive'The consulting company's involvement in the opioid crisis did not stop at helping the companies to launch their products – it also helped them to boost the sales.While the pills like the ones produced by Endo, Purdue and Mallinckrodt were originally advertised as not causing additions, US doctors were not always prone to prescribing them, especially when a patient's pain was neither severe nor chronic. According to the revealed documents, McKinsey's consultants helped Purdue, and several other companies, including two J&J subsidiaries, to overcome this "problem".Starting in 2009, McKinsey developed a "segmentation" strategy for Purdue: its analysts divided the company's customers into groups based on their potential thoughts of the product and then formed distinct messages for each group. The customers in this case were doctors prescribing painkillers and the product was opioid drugs. The strategy targeted even doctors who resorted to opioids only in most extreme cases, ensuring them of OxyContin's safety and trying to convince them that there was no point in making their patients suffer.By 2014, the US government started to realize a nascent opioid drug problem was underway and introduced new labeling requirements for such drugs as well as instructions to use them only in cases of severe of chronic pain. Around the same time, OxyContin sales started to decline, prompting Purdue to ask for McKinsey's help once again – this time to overcome the government's policy and precautions.The consultants identified the problem as the company promoting its drug as a less potent opioid amid rampant drug abuse and advised to shift to the "offense" instead, the documents show. They namely advised focusing the salesmen efforts on doctors, who were likely to prescribe OxyContin to a new client not previously taking opioid drugs.Around the same time and amid the 2015 HIV concentrated outbreaks in several states linked to the opioid drugs abuse via injections, McKinsey consulted Endo on promoting its Opana. The company was not concerned about what the CDC named "explosive transmission" of HIV and the Opana's role in it, according to the documents. On the contrary, in summer 2015, it helped Endo rededicate most of its salesmen from other products into a "Sales Force Blitz" – the company almost solely dedicated to selling Opana to around 3,000 physicians in the US.Playing Both SidesOne of the strangest revelations in the documents uncovered by the New York Times is that McKinsey managed to play both sides of the opioid crisis tragedy – helping pharmaceutical companies sell more of "not-so-addiction-resistant" drugs, while also assisting the FDA, other government agencies and state governments, in the fight against the epidemic.In 2017, the FDA finally decided to pull one of the drugs, the more potent Opana, from the market, but not until it made $844 million in revenue with help from McKinsey and played a role in the deaths of thousands of Americans, considered to be the victims of the opioid epidemic. Paradoxically, the same year, McKinsey Senior Partner Tom Latkovic lamented about doctors prescribing opioid painkillers left and right at a health care conference.The bizarre divergence between what McKinsey was advising to the pharmaceutical companies and Latkovic's rhetoric is explained by the fact that he was not a member of the consulting company's pharmaceutical practice, which worked with pharma.Instead, he and his team worked with state governments and health systems to pin down the ways of tackling the opioid crisis, The New York Times said citing two local officials, who used to work on the issue. Their work, however, was partly complicated by McKinsey's pharmaceutical wing, which wanted to greenlight their draft publications in case they could damage their clients.Eventually in 2019, McKinsey finally stopped advising its top client, Perdue, but not until their ties became public during one of the litigations related to the opioid epidemic and initiated by US authorities. One such litigation eventually had McKinsey pay $600 million in settlement without admitting guilt, as well as release the documents related to its work with the pharmaceutical companies.

https://sputnikglobe.com/20220215/crack-pipes-biden-administrations-handling-of-us-opioid-crisis-raising-questions-journo-says-1093049572.html

https://sputnikglobe.com/20211219/north-carolina-rep-claims-opioid-crisis-affects-every-community-in-us-amid-drug-trafficking-surge-1091635997.html

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2022

Tim Korso

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e6/03/0d/1093831826_0:0:216:216_100x100_80_0_0_e3f43a960af0c6c99f7eb8ccbf5f812c.jpg

Tim Korso

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e6/03/0d/1093831826_0:0:216:216_100x100_80_0_0_e3f43a960af0c6c99f7eb8ccbf5f812c.jpg

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Tim Korso

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e6/03/0d/1093831826_0:0:216:216_100x100_80_0_0_e3f43a960af0c6c99f7eb8ccbf5f812c.jpg

us, opioid crisis, us opioid crisis, drugs

us, opioid crisis, us opioid crisis, drugs

'In-Depth Narcotics Experience': McKinsey Advised US Pharmas on How to Turbo Sell Opioids

18:46 GMT 30.06.2022 (Updated: 18:53 GMT 30.06.2022) The US opioid crisis started at the end of the 1990s after doctors began prescribing opioid-based painkillers even in cases of non-severe pain. They were assured that the drug was not addictive, but millions of patients misused the drug and nearly half a million died from overdose or other conditions related to them as a result.

Global consulting giant

McKinsey & Company advised several painkillers producers for 15 years on how to "turbocharge" prescription drug sales largely to blame for starting the opioid epidemic in the US, The New York Times has revealed citing

over 100,000 documents.

The docs emerged as a part of a

settlement deal that McKinsey signed with several state attorneys that sued the company.

Apart from working with Endo, Purdue, and Mallinckrodt, the company also provided "in-depth experience in narcotics" for Johnson & Johnson subsidiaries producing controlled substances. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of US citizens died from overdose, often linked to these very drugs.

According to the disclosed documents, McKinsey helped both Endo and Purdue, the creators of two of the most widespread opioid-based drugs for severe chronic pain, to launch their products Opana and OxyContin in 2006-2008. The firm even advised one of the companies on how to overcome a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) block which it had encountered in 2008.

The FDA blocked Purdue's attempt to release an upgraded version of its OxyContin, which was more difficult to snort or dilute and inject in bloodstream – two methods of the prescription drug's abuse that already had been devised by some of its recipients. In order to help Purdue get the license, McKinsey interviewed an ex-drug dealer on the medication's abuse, prepared docs and even coached the drug firm's officials for meetings with the FDA as the pharmaceutical company knew its drug had been widely abused, the docs suggest.

15 February 2022, 13:00 GMT

Purdue's main competitor, Endo, also released a new version of its painkiller and tried to get it marked as resistant to crushing (for snorting) and diluting (for injections), but the FDA did not allow the latter citing lack of such properties. Nonetheless, the drug's release was a success and coincided with a drop in abuse-resistant OxyContin's sales.

This came, however, at a cost of local epidemics of previously unseen blood disorders in several US states in 2012 – patients were found to be anemic and suffered from kidney failure. Many of them admitted to abusing updated Opana – the new formulae indeed discouraged from snorting it, but still allowed injection abuse. However, the same component that prevented crushing took a great toll on those who tried to inject the drug to get a better high, leading to red blood cells' destruction and organ damage.

The consulting company's involvement in the opioid crisis did not stop at helping the companies to launch their products – it also helped them to boost the sales.

While the pills like the ones produced by Endo, Purdue and Mallinckrodt were originally advertised as not causing additions, US doctors were not always prone to prescribing them, especially when a patient's pain was neither severe nor chronic. According to the revealed documents, McKinsey's consultants helped Purdue, and several other companies, including two J&J subsidiaries, to overcome this "problem".

Starting in 2009, McKinsey developed a "segmentation" strategy for Purdue: its analysts divided the company's customers into groups based on their potential thoughts of the product and then formed distinct messages for each group. The customers in this case were doctors prescribing painkillers and the product was opioid drugs. The strategy targeted even doctors who resorted to opioids only in most extreme cases, ensuring them of OxyContin's safety and trying to convince them that there was no point in making their patients suffer.

The consulting company proposed to achieve this by "[raising] physician comfort levels through appropriate education and support". Purdue tried to convince these doctors that their colleagues had no issues prescribing OxyContin.

By 2014, the US government started to realize a nascent opioid drug problem was underway and introduced new labeling requirements for such drugs as well as instructions to use them only in cases of severe of chronic pain. Around the same time, OxyContin sales started to decline, prompting Purdue to ask for McKinsey's help once again – this time to overcome the government's policy and precautions.

The consultants identified the problem as the company promoting its drug as a less potent opioid amid rampant drug abuse and advised to shift to the "offense" instead, the documents show. They namely advised focusing the salesmen efforts on doctors, who were likely to prescribe OxyContin to a new client not previously taking opioid drugs.

"Physicians with higher OxyContin NBRx to Rx ratio may be more likely to initiate a patient on OxyContin", an extract from a McKinsey presentation for Purdue from January 2014 said.

Around the same time and amid the 2015 HIV concentrated outbreaks in several states linked to the opioid drugs abuse via injections, McKinsey consulted Endo on promoting its Opana. The company was not concerned about what the CDC named "explosive transmission" of HIV and the Opana's role in it, according to the documents. On the contrary, in summer 2015, it helped Endo rededicate most of its salesmen from other products into a "Sales Force Blitz" – the company almost solely dedicated to selling Opana to around 3,000 physicians in the US.

One of McKinsey's consultants was excited over the creation of the "Force", claiming in correspondence with the head of Endo’s painkiller unit that the "fun [begins] on Monday!" with the latter responding "agreed, the fun is just beginning".

One of the strangest revelations in the documents uncovered by the New York Times is that McKinsey managed to play both sides of the opioid crisis tragedy – helping pharmaceutical companies sell more of "not-so-addiction-resistant" drugs, while also assisting the FDA, other government agencies and state governments, in the fight against the epidemic.

In 2017, the FDA finally decided to pull one of the drugs, the more potent Opana, from the market, but not until it made $844 million in revenue with help from McKinsey and played a role in the deaths of thousands of Americans, considered to be the victims of the opioid epidemic. Paradoxically, the same year, McKinsey Senior Partner Tom Latkovic lamented about doctors prescribing opioid painkillers left and right at a health care conference.

"Why do we continue to prescribe, dispense, pay for opioid prescriptions to people that we know, or at least we could know, have an incredibly high propensity to abuse them?" Latkovic wondered.

The bizarre divergence between what McKinsey was advising to the pharmaceutical companies and Latkovic's rhetoric is explained by the fact that he was not a member of the consulting company's pharmaceutical practice, which worked with pharma.

Instead, he and his team worked with state governments and health systems to pin down the ways of tackling the opioid crisis, The New York Times said citing two local officials, who used to work on the issue. Their work, however, was partly complicated by McKinsey's pharmaceutical wing, which wanted to greenlight their draft publications in case they could

damage their clients.

19 December 2021, 01:36 GMT

Eventually in 2019, McKinsey finally stopped advising its top client, Perdue, but not until their ties became public during one of the litigations related to the opioid epidemic and initiated by US authorities. One such litigation eventually had McKinsey pay $600 million in settlement without admitting guilt, as well as release the documents related to its work with the pharmaceutical companies.