https://sputnikglobe.com/20220708/abe-was-japans-fourth-prime-minister-to-be-assassinated-in-101-years-1097122100.html

Abe Was Japan’s Fourth Prime Minister to be Assassinated in 101 Years

Abe Was Japan’s Fourth Prime Minister to be Assassinated in 101 Years

Sputnik International

The Friday assassination of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was just the latest death in what has been a violent century for Japanese politicians. No... 08.07.2022, Sputnik International

2022-07-08T23:31+0000

2022-07-08T23:31+0000

2023-07-31T17:06+0000

japan

assassination

prime minister

socialist party

militarism

attempted coup

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/107825/00/1078250043_0:0:3073:1728_1920x0_80_0_0_3ab428c952ab7d9c892779ddce087084.jpg

While giving a stump speech in favor of a local politician from his Liberal Democratic Party in Nara on Friday, a gunman approached him from behind and fired two shots using a homemade gun. The gunman was immediately apprehended, but the 67-year-old Abe died of his wounds at a hospital several hours later.At present, the gunman’s motives are unknown. Abe was Japan’s longest serving prime minister and made a wide array of enemies with his controversial political stances, ranging from his visiting of the Yasukuni Shrine and dismissal of the experiences of “comfort women” sex slaves by the Imperial Japanese Army before and during World War 2, to his seeking to remove or amend the neutrality clause of the Japanese constitution that was put in place after the war as a guard against rewenewed Japanese militarism. He resigned for health reasons in 2020.“These two incidents were associated with coup attempts by the military, dissatisfied with the current system of power,” Shinichi said. “On the other hand, it is unlikely that in this case there was such an organizational background. I assume that in this case we are talking about a single crime committed alone.”“What is scary is the future developments,” he added, predicting Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party, which is also the ruling party under Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, would win “an overwhelming majority” in the House of Councillors elections on Sunday.Indeed, several of the most prominent assassinations in Japanese politics over the last century have been deeply connected to issues of militarism and security.Prime Minister Hara Takashi, 1921When Hara became prime minister in September 1918, it was on the heels of the inflation-driven “rice riots” that had forced the resignation of his predecessor, Terauchi Masatake, and months before the end of World War I. Hara was the first commoner to become prime minister, having renounced his family’s low-ranking samurai position and embraced the common man, and the first Christian to hold the position.On November 4, 1921, while waiting for a train to attend a conference in Kyoto for his Rikken Seiyukai (Association of Allies of the Constitution) party at Tokyo Station, a railway switchman stabbed Hara to death, believing him to be corrupt for involving the Zaibatsu business families in Japanese politics and for supporting universal suffrage.Prime Minister Hamaguchi Osachi, 1930-31Hamaguchi was an opposition lawmaker when Hara was killed, a member of the liberal Kenseikai (Constitutional Politics Association) party, later becoming leader of the Minseito (Constitutional Democratic Party) following a merger with another party in 1927. He was tapped to become prime minister in 1929.On November 14, 1930, Hamaguchi was shot in Tokyo Station by an ultranationalist named Tomeo Sagoya, at almost the same place Hama had been killed nine years earlier. He survived the attack, albeit with a severe wound, and although he was elected to a second administration in early 1931, he soon was forced to retire and he died of his wounds on August 26 of that year.Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi, 1932Inukai became prime minister in December 1931, following the short but disastrous administration of Wakatsuki Reijiro, who took over after Hamaguchi’s retirement, and a failed coup attempt by a secret ultranationalist military society. His party, Seiyukai, was a minority in parliament, leaving him with little room to maneuver, and due to cabinet infighting, he leaned on the Privy Council to rule by edict.Three months before Inukai’s death, a group of radical Buddhist mystics and ultranationalist military officers called the League of Blood launched a conspiracy to massacre Japan’s business leaders. They had initially intended to kill 20 of them but instead shot just two: Minseito head and prominent banker Junnosuke Inoue, and the head of the powerful Mitsui Holding Company, Dan Takuma.On May 15, 1932, the League of Blood hatched another assassination plot as 11 naval officers stormed the prime minister’s residence and shot Inukai dead. They also attacked the homes of several leading members of his cabinet and reportedly planned to assassinate American actor Charlie Chaplin in an attempt to provoke a war with the United States. The incident led to the end of any form of civilian control over the Japanese military until the end of World War II.Colonel Denzo Matsuo, 1936The bullet that killed Matsuo on February 26, 1936, was intended for his brother-in-law and boss, Prime Minister Keisuke Okada, to whom he bore a remarkable resemblance.When the conspirators attacked the prime minister’s residence, they faced armed resistance from police, who failed to stop them. Okada was whisked into hiding by Matsuo, who the conspirators then found and killed, believing him to be the prime minister.Okada later escaped and went into hiding, and the emperor ordered the uprising to be crushed, which took three days. Okada resigned a week later. He adamantly opposed war with the US and played a leading role in bringing down the cabinet of Gen. Hideki Tojo in July 1944.Inejiro Asanuma, 1960Asanuma was a charismatic figure on the Japanese left in the postwar era, although his socialist and antiwar views earned him numerous foes. During the era of military rule, he had supported Japan’s imperialist policies, but after, he helped found the Japan Socialist Party while under American occupation.On October 12, 1960, Asanuma was speaking during a televised election debate at Hibiya Public Hall in central Tokyo with the leaders of the Liberal Democratic Party and the Democratic Socialist Party when Otoya Yamaguchi, an acolyte of the far-right Greater Japan Patriotic Party, rushed the stage and stabbed Asanuma in the chest with a 13-inch samurai short sword. He attempted to turn the blade on himself but was stopped and arrested. Asanuma died minutes later. The killing’s dramatic and audacious nature, combined with being broadcast on live television, inspired a number of copycats.

japan

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2022

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

japan, assassination, prime minister, socialist party, militarism, attempted coup

japan, assassination, prime minister, socialist party, militarism, attempted coup

Abe Was Japan’s Fourth Prime Minister to be Assassinated in 101 Years

23:31 GMT 08.07.2022 (Updated: 17:06 GMT 31.07.2023) The Friday assassination of former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was just the latest death in what has been a violent century for Japanese politicians. No less than four head statesmen have been killed by attackers, along with other political leaders.

While giving a stump speech in favor of a local politician from his Liberal Democratic Party in Nara on Friday, a gunman approached him from behind and fired two shots using a homemade gun. The gunman was immediately apprehended, but the 67-year-old

Abe died of his wounds at a hospital several hours later.

At present, the gunman’s motives are unknown. Abe was Japan’s longest serving prime minister and

made a wide array of enemies with his controversial political stances, ranging from his visiting of the Yasukuni Shrine and

dismissal of the experiences of “comfort women” sex slaves by the Imperial Japanese Army before and during World War 2, to his seeking to remove or

amend the neutrality clause of the Japanese constitution that was put in place after the war as a guard against rewenewed Japanese militarism. He resigned for health reasons in 2020.

Nishikawa Shinichi, a Japanese political scientist and professor of political economy at Meiji University, told Sputnik it was “the worst incident in recent Japanese political history.” He recalled several previous incidents in the 1930s, when assassins killed Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi and attempted to kill Prime Minister Keisuke Okada, but noted that in this case, “the motive is completely impossible to predict.”

“These two incidents were associated with coup attempts by the military, dissatisfied with the current system of power,” Shinichi said. “On the other hand, it is unlikely that in this case there was such an organizational background. I assume that in this case we are talking about a single crime committed alone.”

“What is scary is the future developments,” he added, predicting Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party, which is also the ruling party under

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, would win “an overwhelming majority” in the House of Councillors elections on Sunday.

“After that, in the wake of public opinion about the inadmissibility of a repetition of such events, the law on public safety will be strengthened, which may lead to a pre-war police regime,” the political scientist predicted.

Indeed, several of the most prominent assassinations in Japanese politics over the last century have been deeply connected to issues of militarism and security.

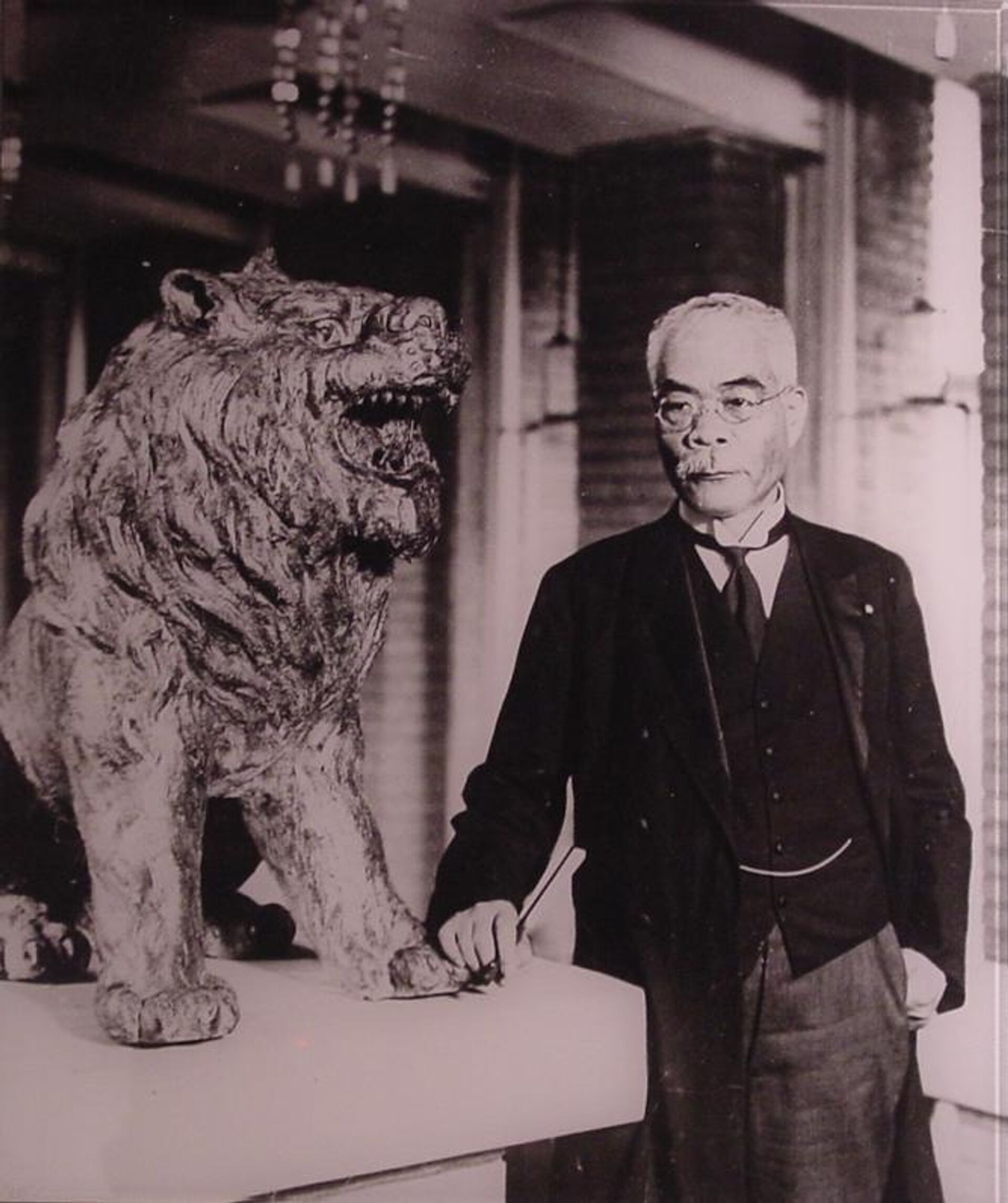

Prime Minister Hara Takashi, 1921

When Hara became prime minister in September 1918, it was on the heels of the inflation-driven “rice riots” that had forced the resignation of his predecessor, Terauchi Masatake, and months before the end of World War I. Hara was the first commoner to become prime minister, having renounced his family’s low-ranking samurai position and embraced the common man, and the first Christian to hold the position.

As prime minister, Hara implemented conciliatory policies designed to reduce opposition to Japanese rule in the colonies, such as allowing Korea a form of limited self-rule, and he attempted to reduce the power of the military in Japanese politics by appointing civilians to head many offices. These actions won him few friends. However, he was also politically cautious, and aroused even greater fury by refusing to push progressive reforms through the Diet, such as universal suffrage.

On November 4, 1921, while waiting for a train to attend a conference in Kyoto for his Rikken Seiyukai (Association of Allies of the Constitution) party at Tokyo Station, a railway switchman stabbed Hara to death, believing him to be corrupt for involving the Zaibatsu business families in Japanese politics and for supporting universal suffrage.

Prime Minister Hamaguchi Osachi, 1930-31

Hamaguchi was an opposition lawmaker when Hara was killed, a member of the liberal Kenseikai (Constitutional Politics Association) party, later becoming leader of the Minseito (Constitutional Democratic Party) following a merger with another party in 1927. He was tapped to become prime minister in 1929.

Like Hara, Hamaguchi was more interested in domestic reform projects and stabilizing the Japanese Empire over sponsoring adventures that would increase the military’s power. His policies failed to adequately respond to the economic malaise of the Great Depression, and he infuriated the military and ultranationalists by signing the London Naval Treaty, winning him many enemies.

On November 14, 1930, Hamaguchi was shot in Tokyo Station by an ultranationalist named Tomeo Sagoya, at almost the same place Hama had been killed nine years earlier. He survived the attack, albeit with a severe wound, and although he was elected to a second administration in early 1931, he soon was forced to retire and he died of his wounds on August 26 of that year.

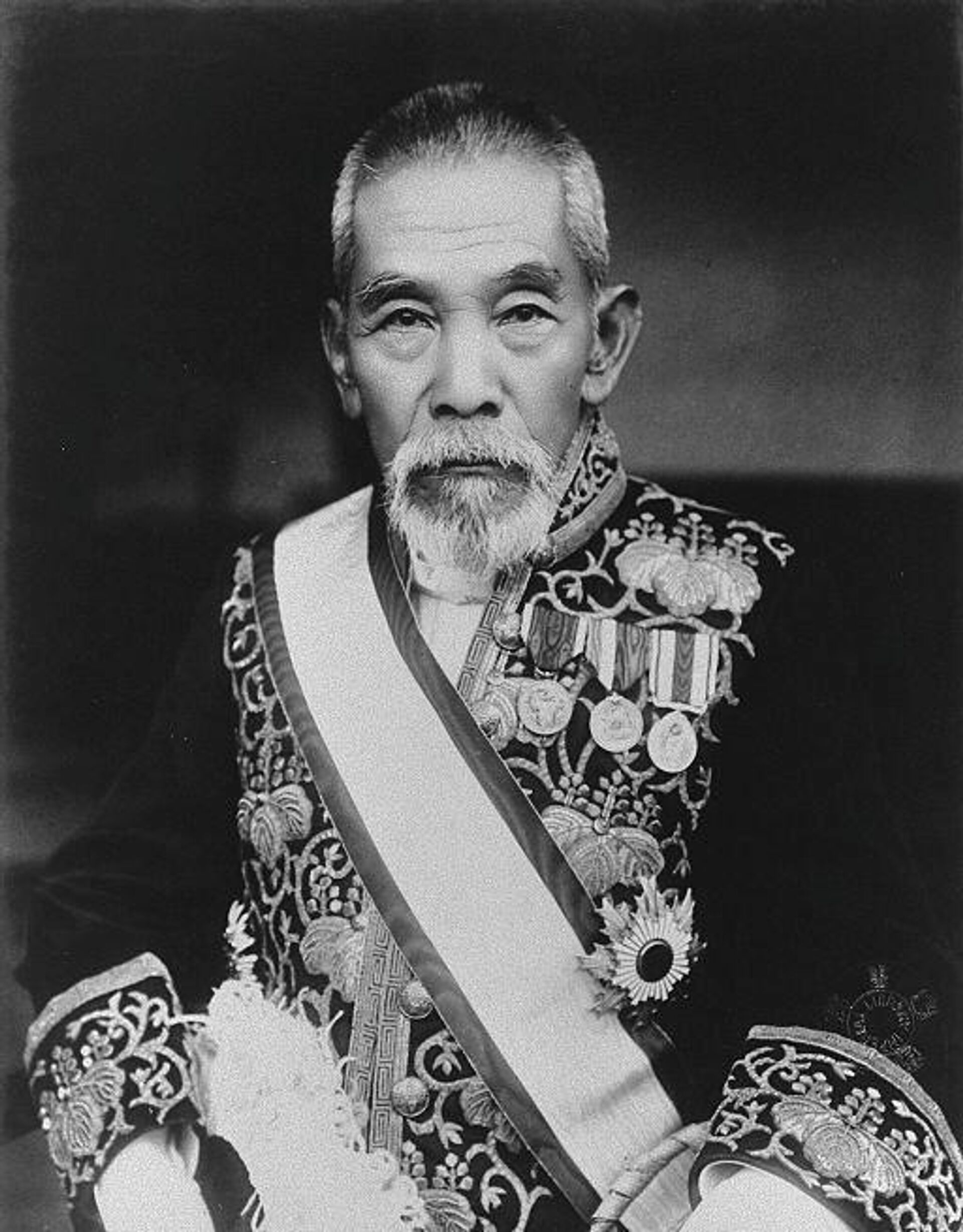

Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi, 1932

Inukai became prime minister in December 1931, following the short but disastrous administration of Wakatsuki Reijiro, who took over after Hamaguchi’s retirement, and a failed coup attempt by a secret ultranationalist military society. His party, Seiyukai, was a minority in parliament, leaving him with little room to maneuver, and due to cabinet infighting, he leaned on the Privy Council to rule by edict.

While Inukai supported the Kwantung Army’s disobedience of imperial orders when it invaded Manchuria in 1931, he refused political recognition to the Manchukuo puppet state the army then set up and sought to rein in the out-of-control military from provoking a greater war with either China or the United States.

Three months before Inukai’s death, a group of radical Buddhist mystics and ultranationalist military officers called the League of Blood launched a conspiracy to massacre Japan’s business leaders. They had initially intended to kill 20 of them but instead shot just two: Minseito head and prominent banker Junnosuke Inoue, and the head of the powerful Mitsui Holding Company, Dan Takuma.

On May 15, 1932, the League of Blood hatched another assassination plot as 11 naval officers stormed the prime minister’s residence and shot Inukai dead. They also attacked the homes of several leading members of his cabinet and reportedly planned to assassinate American actor Charlie Chaplin in an attempt to provoke a war with the United States. The incident led to the end of any form of civilian control over the Japanese military until the end of World War II.

Colonel Denzo Matsuo, 1936

The bullet that killed Matsuo on February 26, 1936, was intended for his brother-in-law and boss, Prime Minister Keisuke Okada, to whom he bore a remarkable resemblance.

Although he was a senior naval officer and decorated veteran, and the Japanese military had already assumed near-total control over the civilian government by the time he took office, Okada was the victim of factional infighting that pro-war conspirators sought to eliminate. They saw Japan’s problems as being caused by straying from the unity of emperor and state and sought to purge what they considered to be corrupt influences that deceived the Showa emperor. As a political moderate who feared Japan’s slide toward open totalitarianism, Okada became a target.

When the conspirators attacked the prime minister’s residence, they faced armed resistance from police, who failed to stop them. Okada was whisked into hiding by Matsuo, who the conspirators then found and killed, believing him to be the prime minister.

Okada later escaped and went into hiding, and the emperor ordered the uprising to be crushed, which took three days. Okada resigned a week later. He adamantly opposed war with the US and played a leading role in bringing down the cabinet of Gen. Hideki Tojo in July 1944.

Asanuma was a charismatic figure on the Japanese left in the postwar era, although his socialist and antiwar views earned him numerous foes. During the era of military rule, he had supported Japan’s imperialist policies, but after, he helped found the Japan Socialist Party while under American occupation.

In 1959, he visited the People’s Republic of China, which the Japanese government did not recognize as the legitimate Chinese government at the time, and was warmly received by Mao Zedong, whom he told the US was "the shared enemy of China and Japan." Upon returning to Japan, Asanuma angered many by wearing a suit similar in style to the Chinese communist leader’s, and he won even more enemies on the far-right by playing a leading role in the protest movement against the US-Japan Security Treaty in 1960 - the largest protests in Japanese history.

On October 12, 1960, Asanuma was speaking during a televised election debate at Hibiya Public Hall in central Tokyo with the leaders of the Liberal Democratic Party and the Democratic Socialist Party when Otoya Yamaguchi, an acolyte of the far-right Greater Japan Patriotic Party, rushed the stage and stabbed Asanuma in the chest with a 13-inch samurai short sword. He attempted to turn the blade on himself but was stopped and arrested. Asanuma died minutes later. The killing’s dramatic and audacious nature, combined with being broadcast on live television, inspired a number of copycats.