https://sputnikglobe.com/20220809/assimilation-exploitation--discrimination-the-unenviable-fate-of-canadas-indigenous-peoples-1099401501.html

Assimilation, Exploitation & Discrimination: The Unenviable Fate of Canada’s Indigenous Peoples

Assimilation, Exploitation & Discrimination: The Unenviable Fate of Canada’s Indigenous Peoples

Sputnik International

Tuesday is the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, a holiday established by the UN to recognize the contributions of indigenous people to... 09.08.2022, Sputnik International

2022-08-09T13:00+0000

2022-08-09T13:00+0000

2022-08-09T16:10+0000

sputnik explains

indigenous peoples

canada

pope francis

discrimination

assimilation

exploitation

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e5/06/08/1083102443_0:160:3073:1888_1920x0_80_0_0_40ef39e52600f43673d1985a27a44399.jpg

Pope Francis’s July 24-29 tour of Canada included a long-overdue apology to Native Canadians for the Catholic Church’s central role in abuses perpetrated at the country’s network of residential schools.The notorious boarding school system was funded and organized by Canada’s federal government and run by Catholic and Protestant churches. It oversaw the forceful and systematic assimilation, abuse, enslavement and even murder of Native Canadian boys and girls from the mid-19th to late 20th centuries. It was a particularly brutal and cruel, but by no means first or only, tool of oppression experienced by indigenous peoples during the European colonialists’ history in North America.The pope assured his apology was “only the first step” of “a serious investigation into the facts of what took place in the past and to assist the survivors of the residential schools to experience healing from the traumas they suffered.”AssimilationMore than 150,000 Native children passed through the residential school system over its 160+ year history. Children were prohibited, often by physical punishment, from speaking their native languages, having their ancestors’ religious concepts replaced with Christianity, and facing their cultural traditions and social norms substituted for those of the colonialists.The first experimental residential school was opened in Brantford, Ontario, in 1833, but the system only became a federally-mandated, national, industrial-scale tool of subjugation in the 1880s after Sir John A Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, ordered the commissioning of a report on the residential school system model being operated in the United States.The report, entitled ‘Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds’, became the basis for Canadian state-church cooperation in solving the Indian “problem” by removing indigenous children from the influences passed down to them by their communities and family units.Along with forced assimilation, students were subjected to other forms of torment, including sexual abuse by priests and teachers, forced labor, and slavery. As of 2021, the National Center for Truth and Reconciliation has been able to identify 4,117 documented deaths of First Nations, Inuit and Metis children in residential schools. However, new graves continue to be discovered, and former Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner Murray Sinclair estimates that more than 6,000 children may have died in the residential school system over the period of its operation.ExploitationResidential schools were by no means the first instance of settlers’ mistreatment of Canada’s indigenous population, with Britain’s victory against the French in the North American theater of the Seven Years’ War of 1754-1763 sealing their fate of subjugation and colonial land grabs, as well as the relentless and cynical exploitation of the most loyal tribes.At the conclusion of the war in 1763, King George III issued a royal proclamation declaring all lands west of the Appalachian Mountains and the colonies of what would ultimately become the early United States as Native territories, outlawing their settlement or purchase by colonialists, and requiring treaty negotiations for any changes to the arrangement. In Canada –organized from the remnants of New France under the name ‘Quebec’, lands to the west and north of the colony were proclaimed Indian territory.Centuries later, scholars continue to fiercely debate the correct interpretation of the proclamation, and whether it was meant as a permanent guarantee of Native rights to lands beyond the then-existent colonies, or a mere opportunity for colonists to catch their breath before continuing an aggressive push west.Even as colonists repeatedly broke the 1763 treaty’s terms throughout the rest of the 18th and 19th centuries through wars of aggression and by taking advantage of divisions within Native tribes through cunning and trickery, many Natives remained loyal to the Crown.Perhaps nowhere was this better exemplified than in the story of Joseph Brant, an 18th-century Mohawk military and political leader who led his warriors in defense of the British Empire during the American Revolutionary War of 1775-1783, and whose efforts proved decisive in halting an American advance into what is now Canada.Brant’s story was repeated in one form or another throughout the 19th century, and today just 0.36 percent of Canada’s total landmass has reserve status for its Native communities.DiscriminationNotwithstanding decades of recognition by successive governments of the historical injustices done to indigenous people, and lip service to improving their social and economic standing, Canada’s community of 1.67 million Natives continues to struggle with a broad spectrum of problems more typically characterizing countries of the so-called Third World than of a thriving, highly developed First World nation.The Council of Canadians estimates that some 73 percent of First Nations’ water systems are at medium or high risk of contamination, with dozens of indigenous communities still lacking basic access to clean drinking water, despite billions of dollars in aid doled out by Ottawa every year to developing countries, and over a billion dollars in support sent to Kiev this year amid the Ukrainian security crisis.Along almost every social indicator, from poverty and access to housing to crime, education, and healthcare, Native communities continue to rank below other Canadians. Nowhere is this exemplified better than in average life expectancy. While other Canadian men and women live on average to an age of 79 and 84 years, respectively, among the First Nations, Metis and Inuit, these figures drop to 72.5 for men and 77.7 for women.

https://sputnikglobe.com/20220728/pope-francis-holds-mass-in-quebec-during-visit-to-canada-to-apologize-to-indigenous-community-1097873315.html

canada

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2022

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

sputnik explains, indigenous peoples, canada, pope francis, discrimination, assimilation, exploitation

sputnik explains, indigenous peoples, canada, pope francis, discrimination, assimilation, exploitation

Assimilation, Exploitation & Discrimination: The Unenviable Fate of Canada’s Indigenous Peoples

13:00 GMT 09.08.2022 (Updated: 16:10 GMT 09.08.2022) Tuesday is the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, a holiday established by the UN to recognize the contributions of indigenous people to their nations and the world. This year, the holiday has been tinged bittersweet by Pope Francis’ historic apology to the Native people of Canada over their mistreatment in residential schools.

Pope Francis’s July 24-29 tour of Canada included a long-overdue apology to Native Canadians for the Catholic Church’s central role in abuses perpetrated at the country’s network of residential schools.

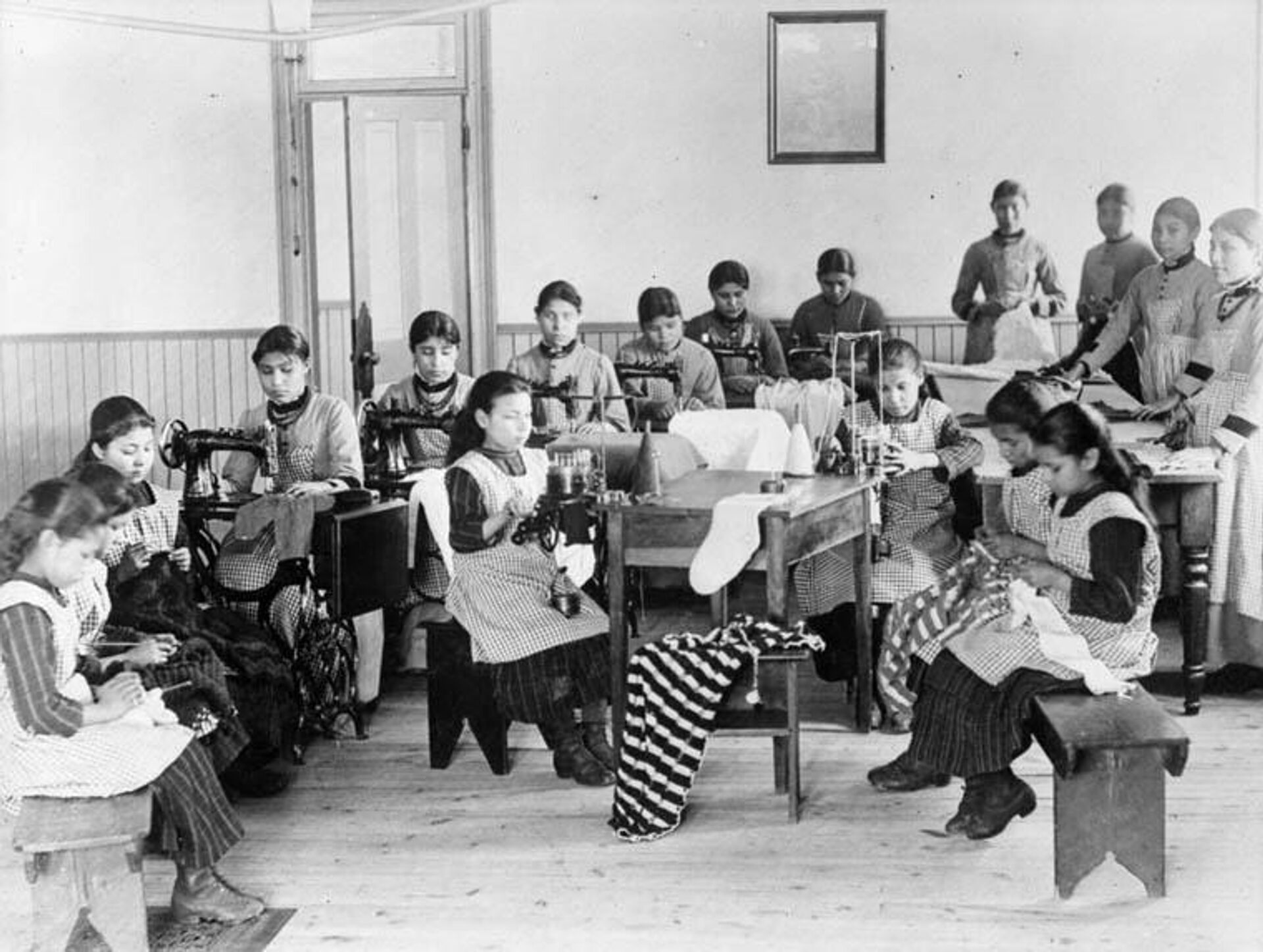

The notorious boarding school system was funded and organized by Canada’s federal government and run by Catholic and Protestant churches. It oversaw the forceful and systematic assimilation, abuse, enslavement and even murder of Native Canadian boys and girls from the mid-19th to late 20th centuries. It was a particularly brutal and cruel, but by no means first or only, tool of oppression experienced by indigenous peoples during the European colonialists’ history in North America.

“I am here because the first step of my penitential pilgrimage among you is that of again asking forgiveness, of telling you once more that I am deeply sorry. Sorry for the ways in which, regrettably, many Christians supported the colonizing mentality of the powers that oppressed the indigenous peoples. I am sorry. I ask for forgiveness, in particular, for the ways in which many members of the Church and of religious communities cooperated, not least through their indifference, in projects of cultural destruction and forced assimilation promoted by the governments of that time, which culminated in the system of residential schools,” Francis

said at the former site of the Ermineskin Residential School in Maskwacis, Alberta on July 25.

The pope assured his apology was “only the first step” of “a serious investigation into the facts of what took place in the past and to assist the survivors of the residential schools to experience healing from the traumas they suffered.”

More than 150,000 Native children passed through the residential school system over its 160+ year history. Children were prohibited, often by physical punishment, from speaking their native languages, having their ancestors’ religious concepts replaced with Christianity, and facing their cultural traditions and social norms substituted for those of the colonialists.

The first experimental residential school was opened in Brantford, Ontario, in 1833, but the system only became a federally-mandated, national, industrial-scale tool of subjugation in the 1880s after Sir John A Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, ordered the commissioning of a report on the residential school system model being operated in the United States.

The report, entitled

‘Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds’, became the basis for Canadian state-church cooperation in solving the Indian “problem” by removing indigenous children from the influences passed down to them by their communities and family units.

Along with forced assimilation, students were subjected to other forms of torment, including

sexual abuse by priests and teachers,

forced labor, and slavery. As of 2021, the National Center for Truth and Reconciliation has been able to identify

4,117 documented deaths of First Nations, Inuit and Metis children in residential schools. However, new graves

continue to be discovered, and former Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner Murray Sinclair estimates that more than 6,000 children may have died in the residential school system over the period of its operation.

In his bombshell 2016 book “Murder by Decree: the Crime of Genocide in Canada,” writer and former United Church of Canada reverend Kevin Annett challenged the NCTR over its conservative estimates on the residential school deaths, detailing the commission’s suppression of eyewitness testimony and archival documentation, and estimating that the true death toll may have run in the tens of thousands. Annett documented how the system included a monthly “death quota” and involved the use of germ warfare, and believes that as many as 50,000 children may have perished in the residential school network.

Residential schools were by no means the first instance of settlers’ mistreatment of Canada’s indigenous population, with Britain’s victory against the French in the North American theater of the Seven Years’ War of 1754-1763 sealing their fate of subjugation and colonial land grabs, as well as the relentless and cynical exploitation of the most loyal tribes.

At the conclusion of the war in 1763, King George III issued a

royal proclamation declaring all lands west of the Appalachian Mountains and the colonies of what would ultimately become the early United States as Native territories, outlawing their settlement or purchase by colonialists, and requiring treaty negotiations for any changes to the arrangement. In Canada –organized from the remnants of New France under the name ‘Quebec’, lands to the west and north of the colony were proclaimed Indian territory.

Centuries later, scholars continue to fiercely debate the correct interpretation of the proclamation, and whether it was meant as a

permanent guarantee of Native rights to lands beyond the then-existent colonies, or a mere

opportunity for colonists to catch their breath before continuing an aggressive push west.

Even as colonists repeatedly broke the 1763 treaty’s terms throughout the rest of the 18th and 19th centuries through wars of aggression and by taking advantage of divisions within Native tribes through cunning and trickery, many Natives remained loyal to the Crown.

Perhaps nowhere was this better exemplified than in the story of Joseph Brant, an 18th-century Mohawk military and political leader who led his warriors in defense of the British Empire during the American Revolutionary War of 1775-1783, and whose efforts

proved decisive in halting an American advance into what is now Canada.

In return for the loyalty shown by Brant and his fellow Mohawks, Quebec Governor Sir Frederick Haldimand promised that after the war, his people would be granted more than 8,090 square km of land around the Grand River Basin in southern Ontario. However, after the war ended in 1783, the settlers would gradually chip away at their commitments, with the Native-administered area now known as the Six Nations Reserve shrinking to just 183 square km of land, two percent of what Brant was originally promised.

Brant’s story was repeated in one form or another throughout the 19th century, and today just

0.36 percent of Canada’s total landmass has reserve status for its Native communities.

Notwithstanding decades of recognition by successive governments of the historical injustices done to indigenous people, and lip service to improving their social and economic standing, Canada’s community of 1.67 million Natives continues to struggle with a broad spectrum of problems more typically characterizing countries of the so-called

Third World than of a thriving, highly developed First World nation.

The Council of Canadians estimates that some

73 percent of First Nations’ water systems are at medium or high risk of contamination, with

dozens of indigenous communities still lacking basic access to clean drinking water,

despite billions of dollars in aid doled out by Ottawa every year to developing countries, and

over a billion dollars in support sent to Kiev this year amid the Ukrainian security crisis.

Along almost every social indicator, from

poverty and access to housing to

crime,

education, and

healthcare, Native communities continue to rank below other Canadians. Nowhere is this exemplified better than in average life expectancy. While other Canadian men and women live on average to an age of 79 and 84 years, respectively, among the First Nations, Metis and Inuit, these figures

drop to 72.5 for men and 77.7 for women.