https://sputnikglobe.com/20221028/we-want-to-rule-italy-100-years-since-mussolinis-march-on-rome-brought-fascism-to-europe-1102808633.html

‘We Want to Rule Italy’: 100 Years Since Mussolini’s March on Rome Brought Fascism to Europe

‘We Want to Rule Italy’: 100 Years Since Mussolini’s March on Rome Brought Fascism to Europe

Sputnik International

Italians on Friday marked the centenary anniversary of the March on Rome, a fascist coup d’etat by Benito Mussolini. The 1922 seizure of power marked the first... 28.10.2022, Sputnik International

2022-10-28T19:50+0000

2022-10-28T19:50+0000

2023-07-31T17:15+0000

world

benito mussolini

rome

fascism

coup d'etat

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/106399/76/1063997636_0:198:2278:1479_1920x0_80_0_0_e647c79b2eefa315c51c2f01acaa4e39.jpg

However, the fascist rise to power didn’t spring out of the blue: it came about through intense class struggle in Italy during the years immediately following World War I. The British Empire, fearful of the rise of communism, also helped grease the wheels for the fascist coup.Biennio Rosso - Two Red YearsAlthough the Great War produced widespread misery and suffering across the “home front” of every nation that joined the conflict, Italy’s socioeconomic malaise was amplified by its semi-industrialized character.After the war and demobilization came high unemployment and rapid inflation, sending the cost of goods sky-high. Socialist and anarchist movements had grown strong during the war, and during the economic crisis, their ranks expanded rapidly. Trade unions became increasingly militant, launching not just strikes but factory takeovers. Membership in the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) reached 250,000, and the anarchist Italian Syndicalist Union (USI) reached perhaps 500,000 members.The years 1919 and 1920 became known afterward as the Biennio Rosso - the Two Red Years, for this intense radicalization of Italian society. In one town after another, socialists and other leftists won elections and dominated civil society groups. With the triumph of the Bolsheviks in Russia in the 1917 revolution and the civil war that followed, and the bubbling communism in almost every Western European country as well as the United States, it seemed like Italy might be where they rose to power next.Ruling Class Strikes BackHowever, the bourgeoisie of every Western European nation was terrified by the events in Soviet Russia and looked desperately for a way to roll back the Red Tide. In Germany, armed veterans organized into Freikorps had suppressed a communist revolt, but elsewhere, many questioned if the regular army soldiers, drawn from working-class families themselves, could be relied upon to suppress revolution.The Blackshirts went into the towns controlled by socialists and attacked union organizers and municipal administrators, obstructing the basic operations of their governments. Those who escaped the beatings and lynchings were driven out of town, and by the end of 1921, the Biennio Rosso had ended in an orgy of right-wing violence, and a new Fascist Party led by Benito Mussolini was rapidly replacing socialist politicians with their own. Its rapid rise to power was aided by alliances with liberal parties, who also feared a socialist victory.Documents in the UK National Archives show that Sir Samuel Hoare, who headed the British overseas intelligence service, MI1(c), in Rome at the end of the war, had established contact with Mussolini, a former socialist who had rejected the party’s anti-war stance in 1914 and become a staunch pro-war nationalist.Hoare’s goal was to keep Italy from dropping out of the war early and signing a separate peace with the Central Powers. He gave Mussolini £100 a week to keep his pro-war newspaper publishing. Hoare was not shy about this, later saying that British money had been used to “form the Fascist Party and to finance the march on Rome.”Quadrumvirs March on RomeThe socialists attempted to block the Fascist rise to power with a general strike in August 1922, but Mussolini used the incident to position the Fascists as the defenders of law and order in Italy, and appealed to the Italian government to arm the Fascists and let them suppress the strikers. The police did not act.As the fall of 1922 wore on, so did a crisis in the Italian parliament, which had proved unable to form a stable government. Here, Mussolini saw an opportunity: where he had previously been something of an iconoclast, he now made open appeals to the Catholic Church and to industrial magnates in the interests of restoring order.On October 24, Mussolini named four “quadrumvirs,” another term from Ancient Rome that was used to describe a group of four people sharing police and jurisdiction power. Each was to lead a column of Fascists and supporters to Rome and force the government of Prime Minister Luigi Facta to yield power.However, Mussolini did not participate in the march itself, and awaited the results of the coup from the northern city of Milan.According to the Times, documents in the UK National Archives show that in the days prior to the March on Rome, the British ambassador to Italy, Sir Ronald Graham, met in Perugia with many of its top leaders. During the march, Graham told London his secretary was being “constantly” updated by the marchers as they neared the Italian capital in Rome.On October 28, some 30,000 Fascists were closing in on Rome, and Facta tried to order a mobilization of troops by declaring a state of siege. However, the king refused to sign the order, and negotiations with Mussolini began. That day, representatives from the country’s leading industrial organizations met with Mussolini in Milan and proposed that he share power with former Prime Minister Antonio Solandra, but he refused.Power SolidifiedContrary to how Mussolini presented his ideology and rise to power in his 1932 book “The Doctrine of Fascism,” it was not all planned out beforehand, but a hodgepodge of useful ideological turns and political jockeying that slowly accumulated power in his hands.The situation was viewed with skepticism by some abroad, but by others, it was welcomed. During a 1927 trip to Rome to meet with Mussolini, Winston Churchill, then chancellor of the British exchequer, was full of ebullient praise for the Fascist movement.Despite the dictatorship, anti-fascist resistance continued underground, and played a vital role in the Second World War as Allied forces prepared to invade the country. In 1936, Mussolini allied with another fascist leader, Adolf Hitler, who had seized power in Germany three years earlier amid a similar economic crisis and class conflict. However, Mussolini did not share Hitler’s racial theories, and a number of high-ranking fascists were Jewish. However, antisemitism became more intense amid their alliance, and racial laws began in 1938 that targeted both Jews and Ethiopians, whose country Mussolini had invaded in 1935.Mussolini was eventually overthrown in 1943 by the king who had empowered him, and the new government signed an armistice with the invading Allies. However, he was freed after Nazi German forces seized power in the remaining parts of the country. The country devolved into civil war, and two years later, on April 28, 1945, Italian resistance forces finally caught up to Mussolini, arrested him and executed him in the small village of Giulino di Mezzegra, leaving his body hanging in the public square.

rome

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2022

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

benito mussolini, rome, fascism, coup d'etat

benito mussolini, rome, fascism, coup d'etat

‘We Want to Rule Italy’: 100 Years Since Mussolini’s March on Rome Brought Fascism to Europe

19:50 GMT 28.10.2022 (Updated: 17:15 GMT 31.07.2023) Longread

Italians on Friday marked the centenary anniversary of the March on Rome, a fascist coup d’etat by Benito Mussolini. The 1922 seizure of power marked the first time a fascist movement came to power in Europe - a grim sign of the continent’s future for the next two decades.

However, the fascist rise to power didn’t spring out of the blue: it came about through intense class struggle in Italy during the years immediately following World War I. The British Empire, fearful of the rise of communism, also helped grease the wheels for the fascist coup.

Biennio Rosso - Two Red Years

Although the Great War produced widespread misery and suffering across the “home front” of every nation that joined the conflict, Italy’s socioeconomic malaise was amplified by its semi-industrialized character.

In the northern cities, industrialization had taken hold and a powerful banker class had risen to prominence, which dreamed of a new empire befitting an Italy reunited for the first time since the Roman Empire. In the south, including Sicily and Sardinia, an agrarian way of life still held sway among populations who a generation prior had never spoken the Italian language.

After the war and demobilization came high unemployment and rapid inflation, sending the cost of goods sky-high. Socialist and anarchist movements had grown strong during the war, and during the economic crisis, their ranks expanded rapidly. Trade unions became increasingly militant, launching not just strikes but factory takeovers. Membership in the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) reached 250,000, and the anarchist Italian Syndicalist Union (USI) reached perhaps 500,000 members.

The years 1919 and 1920 became known afterward as the Biennio Rosso - the Two Red Years, for this intense radicalization of Italian society. In one town after another, socialists and other leftists won elections and dominated civil society groups. With the triumph of the Bolsheviks in Russia in the 1917 revolution and the civil war that followed, and the bubbling communism in almost every Western European country as well as the United States, it seemed like Italy might be where they rose to power next.

Ruling Class Strikes Back

However, the bourgeoisie of every Western European nation was terrified by the events in Soviet Russia and looked desperately for a way to roll back the Red Tide. In Germany, armed veterans organized into Freikorps had suppressed a communist revolt, but elsewhere, many questioned if the regular army soldiers, drawn from working-class families themselves, could be relied upon to suppress revolution.

Out of this cauldron of class conflict came the Squadristi, gangs of thugs employed by capitalists who were furious and fearful at the socialists’ factory seizures. They were better known as the “Blackshirts” for their impromptu uniforms.

The Blackshirts went into the towns controlled by socialists and attacked union organizers and municipal administrators, obstructing the basic operations of their governments. Those who escaped the beatings and lynchings were driven out of town, and by the end of 1921, the Biennio Rosso had ended in an orgy of right-wing violence, and a new Fascist Party led by

Benito Mussolini was rapidly replacing socialist politicians with their own. Its rapid rise to power was aided by alliances with liberal parties, who also feared a socialist victory.

The name "fascist" came from the fasces, a bound bundle of sticks topped with an ax - the symbol of legal authority in Ancient Rome. Many liberal movements had previously used the symbol to identify themselves with the republicanism of Ancient Rome, but Mussolini used it to evoke the supremacy of the law and of the state, and the powerful nationalist desire to build a new Roman Empire in the 20th century.

Documents in the UK National Archives show that Sir Samuel Hoare, who headed the British overseas intelligence service, MI1(c), in Rome at the end of the war, had established contact with Mussolini, a former socialist who had rejected the party’s anti-war stance in 1914 and become a staunch pro-war nationalist.

Hoare’s goal was to keep Italy from dropping out of the war early and signing a separate peace with the Central Powers. He gave Mussolini £100 a week to keep his pro-war newspaper publishing. Hoare was not shy about this, later saying that British money had been used to “form the Fascist Party and to finance the march on Rome.”

Quadrumvirs March on Rome

The socialists attempted to block the Fascist rise to power with a general strike in August 1922, but Mussolini used the incident to position the Fascists as the defenders of law and order in Italy, and appealed to the Italian government to arm the Fascists and let them suppress the strikers. The police did not act.

A

New York Times headline from mid-September bluntly declared “bourgeoisie new class war victor: Italy’s general strike brings novel armed forces into arena, socialist structure crumbling as a consequence.”

As the fall of 1922 wore on, so did a crisis in the Italian parliament, which had proved unable to form a stable government. Here, Mussolini saw an opportunity: where he had previously been something of an iconoclast, he now made open appeals to the Catholic Church and to industrial magnates in the interests of restoring order.

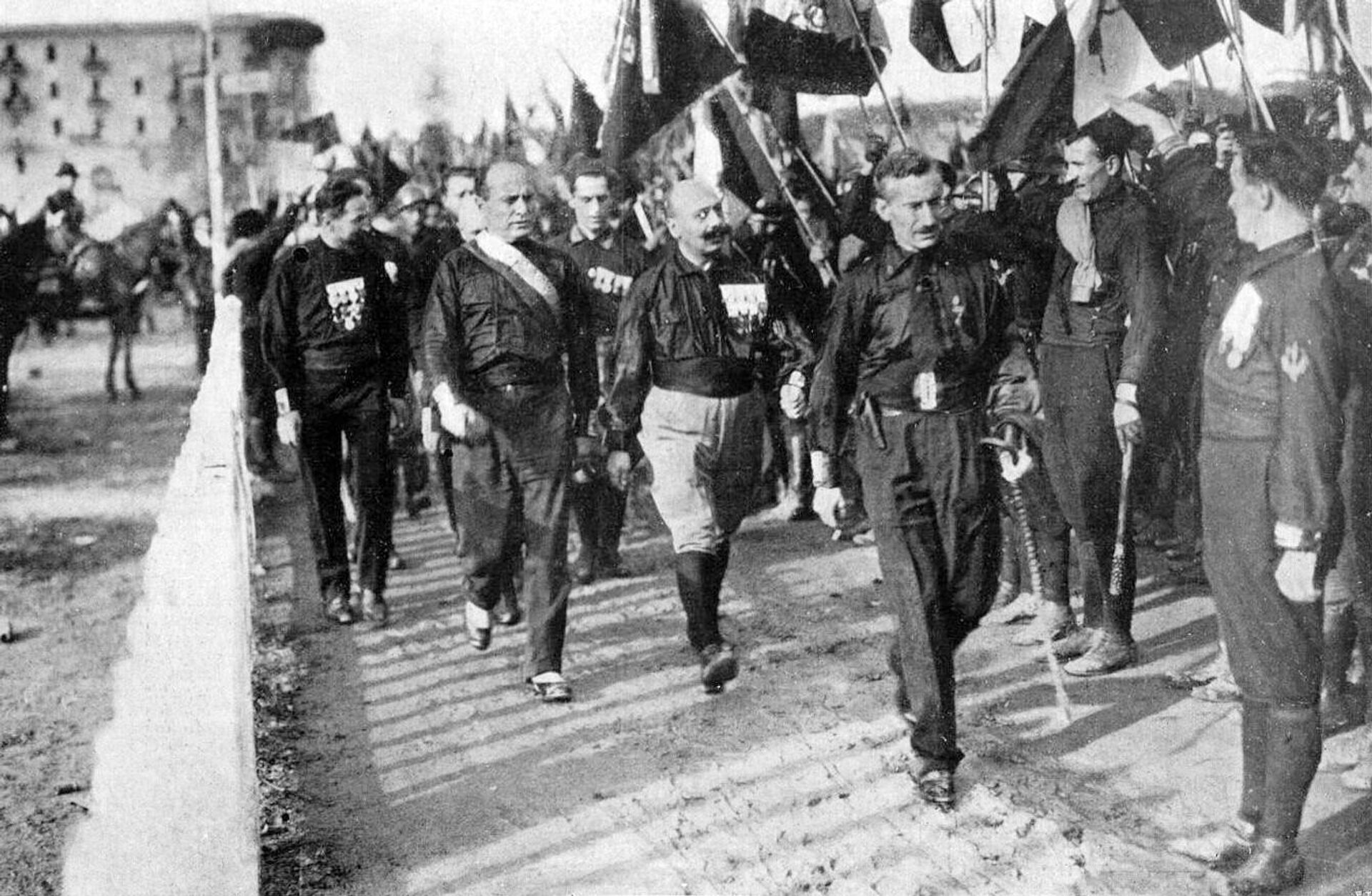

On October 24, Mussolini named four “quadrumvirs,” another term from Ancient Rome that was used to describe a group of four people sharing police and jurisdiction power. Each was to lead a column of Fascists and supporters to Rome and force the government of Prime Minister Luigi Facta to yield power.

"Our program is simple,” Mussolini said to a crowd of 60,000 Fascists in Naples on October 24, “we want to rule Italy."

However, Mussolini did not participate in the march itself, and awaited the results of the coup from the northern city of Milan.

“The British helped orchestrate the march and propel Mussolini to power because they wanted to make him the key figure in a government which would be useful to them,” Giovanni Fasanella, who co-authored the forthcoming book “Nero di Londra” with Mario José Cereghino,

told the Times of London.

According to the Times, documents in the UK National Archives show that in the days prior to the March on Rome, the British ambassador to Italy, Sir Ronald Graham, met in Perugia with many of its top leaders. During the march, Graham told London his secretary was being “constantly” updated by the marchers as they neared the Italian capital in Rome.

“We believe the ambassador was giving the Fascists useful advice,” the book’s second co-author, Cereghino, told the paper.

On October 28, some 30,000 Fascists were closing in on Rome, and Facta tried to order a mobilization of troops by declaring a state of siege. However, the king refused to sign the order, and negotiations with Mussolini began. That day, representatives from the country’s leading industrial organizations met with Mussolini in Milan and proposed that he share power with former Prime Minister Antonio Solandra, but he refused.

The following day, King Victor Emmanuel III offered Mussolini the chance to form a government and become prime minister. Mussolini accepted, and various liberal and Catholic parties formed a coalition government with the Fascists.

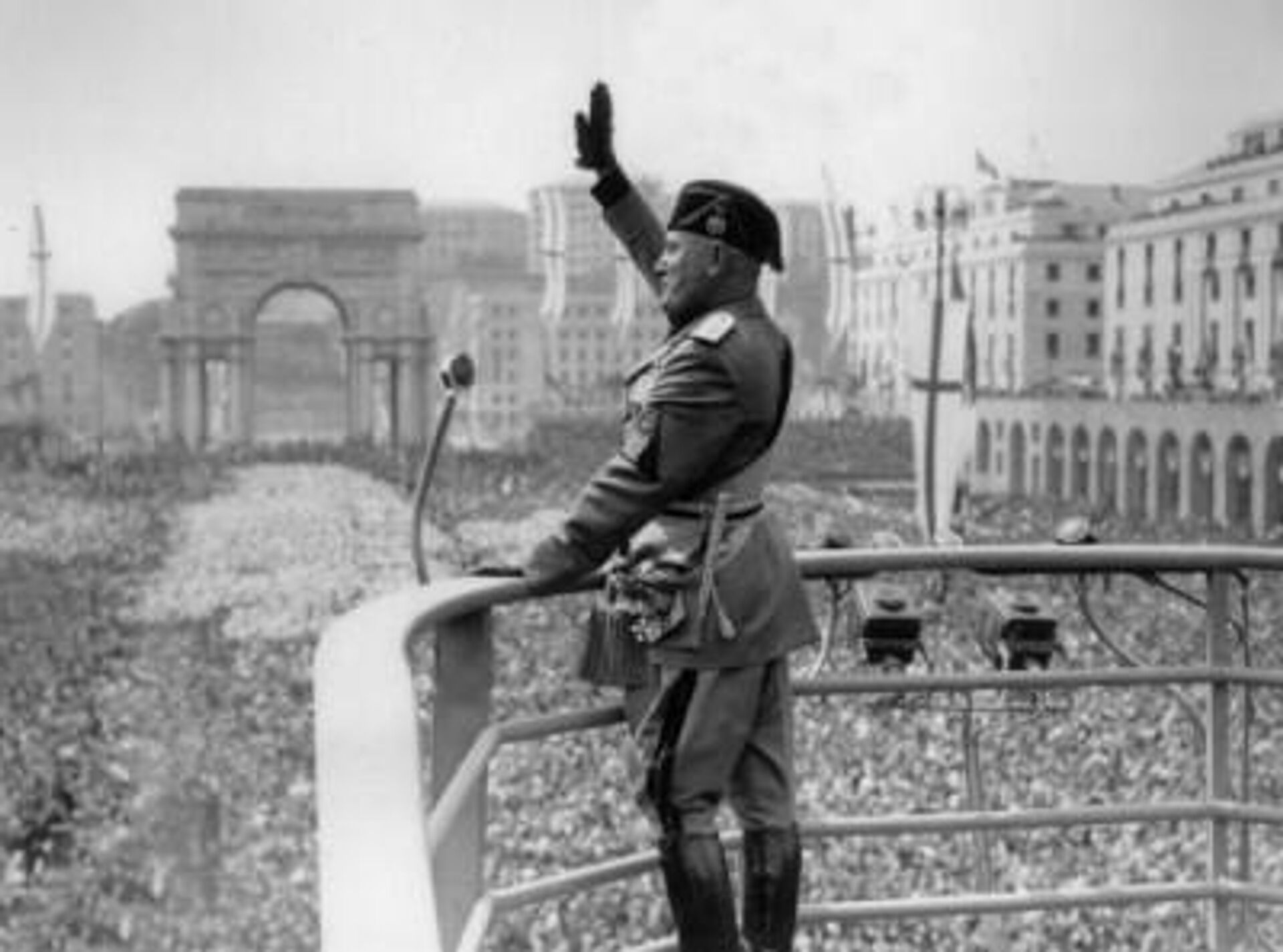

Contrary to how Mussolini presented his ideology and rise to power in his 1932 book “The Doctrine of Fascism,” it was not all planned out beforehand, but a hodgepodge of useful ideological turns and political jockeying that slowly accumulated power in his hands.

It wasn’t until 1925 that the Fascist dictatorship was complete, after years of chipping away at the electoral system had left the party in almost total control over the government. Mussolini finalized the situation by declaring the National Fascist Party the only legal party.

The situation was viewed with skepticism by some abroad, but by others, it was welcomed. During a 1927 trip to Rome to meet with Mussolini, Winston Churchill, then chancellor of the British exchequer, was full of ebullient praise for the Fascist movement.

“If I had been an Italian, I am sure I should have been whole-heartedly with you from start to finish in your triumphant struggle against the bestial appetites and passions of Leninism,”

Churchill told a Roman crowd. He also said of Mussolini: “No doubt he is one of the most wonderful men of our time.”

Despite the dictatorship, anti-fascist resistance continued underground, and played a vital role in the Second World War as Allied forces prepared to invade the country. In 1936, Mussolini allied with another fascist leader, Adolf Hitler, who had seized power in Germany three years earlier amid a similar economic crisis and class conflict. However, Mussolini did not share Hitler’s racial theories, and a number of high-ranking fascists were Jewish. However, antisemitism became more intense amid their alliance, and racial laws began in 1938 that targeted both Jews and Ethiopians, whose country Mussolini had invaded in 1935.

Mussolini was eventually overthrown in 1943 by the king who had empowered him, and the new government signed an armistice with the invading Allies. However, he was freed after Nazi German forces seized power in the remaining parts of the country. The country devolved into civil war, and two years later, on April 28, 1945, Italian resistance forces finally caught up to Mussolini, arrested him and executed him in the small village of Giulino di Mezzegra, leaving his body

hanging in the public square.