Mysterious 'Blob' in Pacific Ocean Years Ago Still Taking Its Toll on Struggling Marine Life

11:31 GMT 19.11.2022 (Updated: 10:42 GMT 21.04.2023)

© BORIS HORVAT

Subscribe

Over the last decade, an abnormally warm for its location and season mass of water in the North Pacific, dubbed "The Blob", has resurfaced on a number of occasions to lay waste to ecosystems in the area, and has been faulted for several instances of mass die-off of species of fish and birds.

Just like its namesake – a 1958 American science fiction horror flick – ‘the Blob' continues to wreak damage on marine ecosystems, despite last officially seen six years ago, a study revealed.

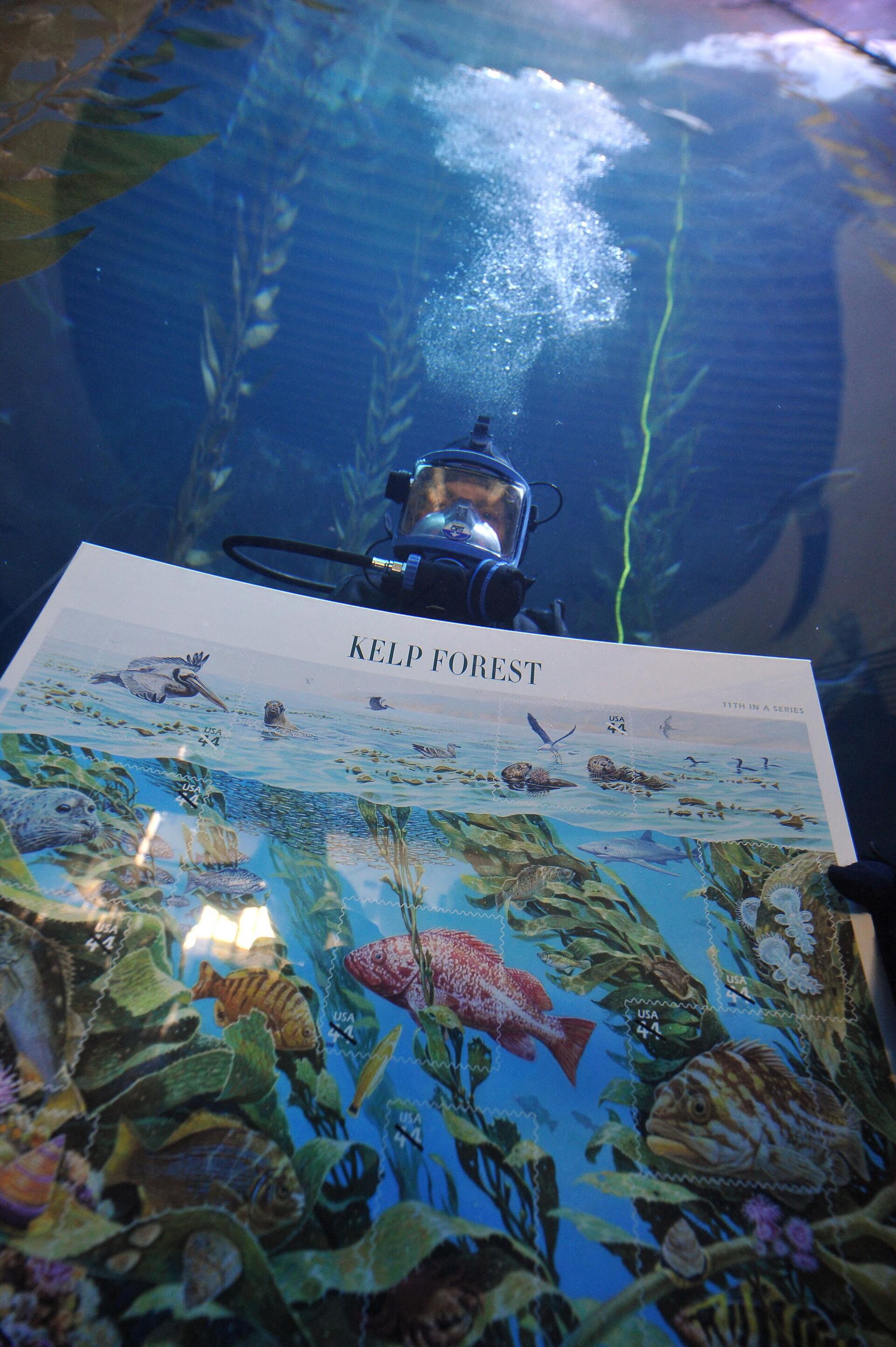

The inhabitants of the kelp forest ecosystem on the Santa Barbara Channel, off the Californian coast, are still reeling from the environmental impact of the phenomenon, according to the University of California team of scientists.

Rocky reefs hugging the shoreline of the Channel are populated with various species of fish, mollusks, algae and other marine life. The Pacific Ocean witnessed what was termed an extreme marine heatwave a few years back, first discovered in 2013 and given the not-so-endearing nickname of 'The Blob'. At the time, the huge circle-shaped mass of water stubbornly refused to cool the way it was typically expected to in accordance with its location and the season. While appearing to fade and vanish sometime in 2016, it left marine life struggling to deal with the disruption to its familiar habitat.

This anomalously warm pool of water in the North Pacific dubbed "The Blob" has made several appearances over the last decade, leading to documented changes in climate and marine ecosystems, including mass die-off of fish and birds. pic.twitter.com/C1Rb5Jtg0I

— Colin McCarthy (@US_Stormwatch) July 26, 2022

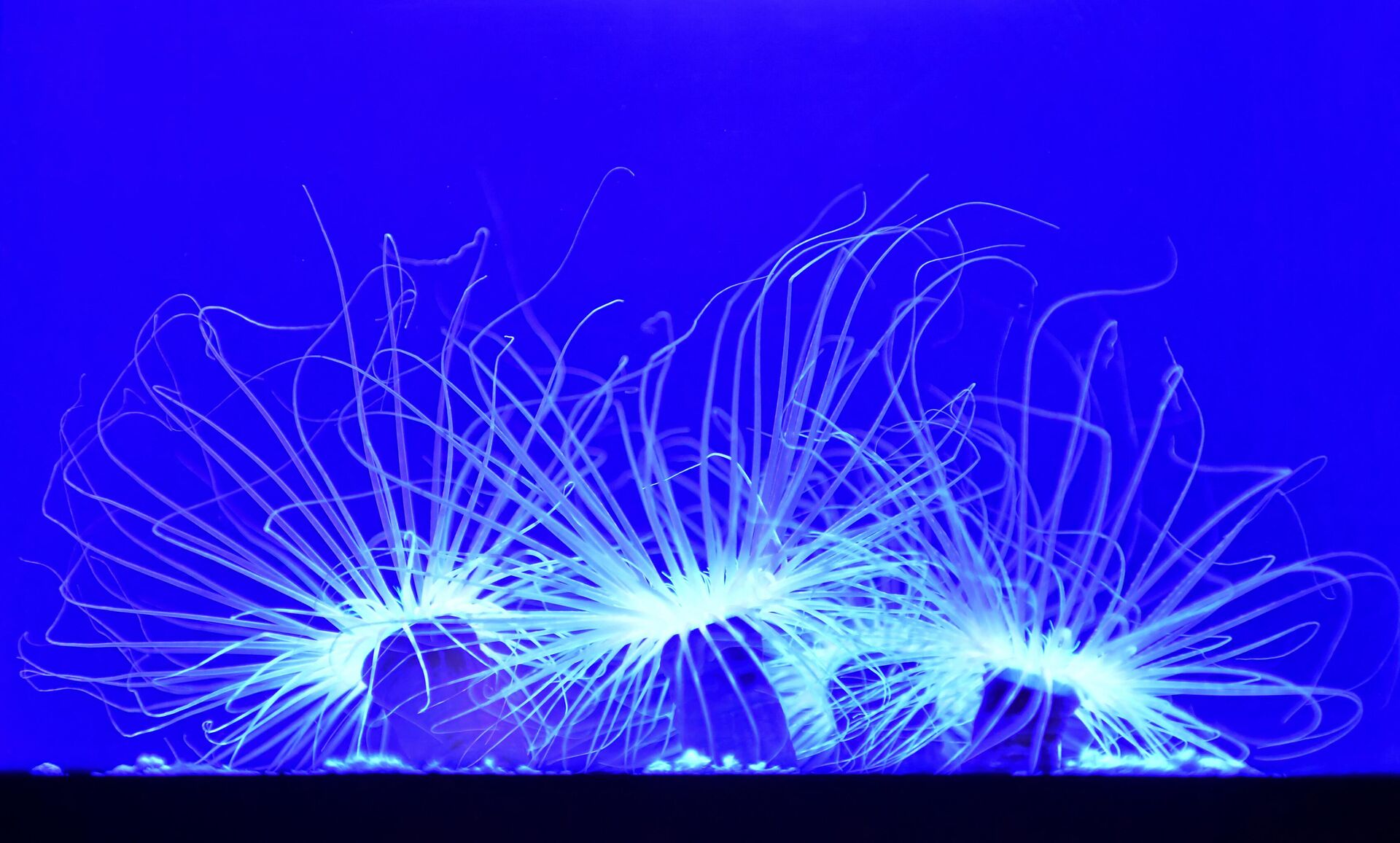

The greatest-affected at the time were sessile animals, in other words, those that lack self-locomotion means and are stuck clinging to one place, like anemones, pointed out the research published in Communications Biology.

Tube-dwelling Anemones, a solitary creature living buried in soft sediments, seen at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, California on May 27, 2021.

© FREDERIC J. BROWN

Sessile invertebrates that reside clinging to the reefs have shown encouraging signs of population regrowth, said the study. Throughout the year 2015, when ‘the Blob’ raged across the affected section of the Pacific, their numbers originally plummeted by 71 percent.

The reason for this was that the much warmer water left marine creatures like anemones, tubeworms, and clams sorely lacking phytoplankton that they use as a nutrient. Plankton, in turn, feeds on nutrients that the colder seawater carries. And if that problem wasn’t enough, the metabolisms of the sessile invertebrates was boosted by the heat anomaly, making them extra-ravenous.

In the warmer waters brought by ‘the Blob’, particularly invasive species such as Watersipora subatra and Bugula neritina thrived, said the researchers. The tiny tentacled bryozoans live in a colony as one organism.

"The groups of animals that seemed to be the winners, at least during the warm period, were longer-lived species, like clams and sea anemones. But after the Blob, the story is a little different. Bryozoan cover increased quite rapidly, and there are two species of invasive bryozoans that are now much more abundant," Kristen Michaud, an ecologist from the University of California, Santa Barbara, told the media.

The Boom of the W. subatra and B. neritina is likely due to the fact that they display a resilience to conditions of higher temperatures, and can jostle aggressively for space on the reefs. Another sessile gastropod - the scaled worm snail, or Thylacodes squamigerous - has also thrived despite the shakup of its habitat at the time of the anomaly.

A diver displays the US Postal Service’s newest 44-cent First-Class postage stamps called "Nature of America: Kelp Forest."

© AFP 2023 / ROBYN BECK

The scientists underscored that as ‘newcomers’ to the ecosystems ‘post-Blob’ take on a role different from the creatures that they replaced, more research is needed to forecast long-term effects for the marine life.