https://sputnikglobe.com/20230107/built-to-last-mystery-ingredient-helped-roman-architectural-gems-to-weather-time-study-shows-1106110500.html

Built to Last: Mystery Ingredient Helped Roman Architectural Gems to Weather Time, Study Shows

Built to Last: Mystery Ingredient Helped Roman Architectural Gems to Weather Time, Study Shows

Sputnik International

Majestic Roman structures, from the Pantheon to the iconic Colosseum, unfailingly capture our imagination, whether we behold them “in the flesh” or they gaze... 07.01.2023, Sputnik International

2023-01-07T14:19+0000

2023-01-07T14:19+0000

2023-01-07T14:19+0000

science & tech

roman

colosseum

concrete

ancient rome

cement

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/107857/41/1078574184_0:160:3073:1888_1920x0_80_0_0_17b0cb2a793c180349ecd5c061344969.jpg

There is a mysterious "ingredient" that explains why Roman buildings have survived so long, a new study claims.The intriguing durability of ancient Roman concrete, which has survived millennia, is what a team of scientists from the United States, Italy, and Switzerland decided to probe, publishing their findings in the journal Science Advances.It has been thousands of years, yet traces of the Roman Empire have survived to our day and age, inspiring generations that followed. Ancient Romans built to last, whether it was temples, houses, or aqueducts. Lasting reminders of the once flamboyant Roman Empire, awe-inspiring architectural marvels such as the famous amphitheater, the Colosseum, the well-preserved Pantheon, and the architectural gem of Maison Carrée temple in Nimes. 'Self-Healing' Process2,000-year-old samples of concrete, taken from a city wall at the archaeological site of Privernum, in central Italy, were analyzed by the study team. The white chunks discovered in the concrete, previously believed to be fragments of poor-quality raw material, in actual fact lent the concrete the ability to heal cracks forming with the onslaught of time.Referring to the earlier speculation that the chunks, referred to as lime clasts, were just evidence of sloppiness on the part of the Roman builders, study author Admir Masic, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said:Roman texts studied by researchers had appeared to indicate that slaked lime was resorted to as a binding agent in making concrete. Concrete is formed by mixing cement, a binding agent typically made from limestone, water, fine aggregate like sand, and coarse aggregate, such as crushed rock. But the researchers concluded that the chunks, or lime clasts, occurred due to use of quicklime (calcium oxide) when mixing the concrete, rather than or in addition to slaked lime.The team carried out analysis of the concrete, finding that "hot mixing" explained the concrete's durable characteristics.The study conducted an experiment to prove the truth of their findings. They made two samples of concrete, one corresponding to ancient Roman formulas, and the other in line with modern standards. Then they deliberately cracked them and waited for two weeks. By that time, while water seeped through the modern-day type of concrete, the cracks in the concrete made following Roman recipes had "healed."The results confirmed that lime clasts could dissolve into cracks and subsequently recrystallize after exposure to water in a "self-healing" process that could now be used to producing more long-lasting modern concrete.

https://sputnikglobe.com/20221124/roman-coins-rescue-forgotten-emperor-back-from-oblivion-1104626889.html

https://sputnikglobe.com/20220706/severe-drought-causing-ruins-of-ancient-roman-bridge-built-under-neros-reign-to-reemerge-from-tiber-1097028891.html

ancient rome

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2023

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

science & tech, roman, colosseum, concrete, ancient rome, cement

science & tech, roman, colosseum, concrete, ancient rome, cement

Built to Last: Mystery Ingredient Helped Roman Architectural Gems to Weather Time, Study Shows

Majestic Roman structures, from the Pantheon to the iconic Colosseum, unfailingly capture our imagination, whether we behold them “in the flesh” or they gaze at us from picture postcards. But how often do we stop to ponder the engineering ingenuity behind their creation?

There is a mysterious "ingredient" that explains why Roman buildings have survived so long, a new study claims.

The intriguing durability of ancient Roman concrete, which has survived millennia, is what a team of scientists from the United States, Italy, and Switzerland decided to probe, publishing their findings in the

journal Science Advances.It has been thousands of years, yet traces of the

Roman Empire have survived to our day and age, inspiring generations that followed. Ancient Romans built to last, whether it was temples, houses, or aqueducts. Lasting reminders of the once flamboyant Roman Empire, awe-inspiring architectural marvels such as the famous amphitheater,

the Colosseum, the well-preserved Pantheon, and the architectural gem of Maison Carrée temple in Nimes.

24 November 2022, 12:33 GMT

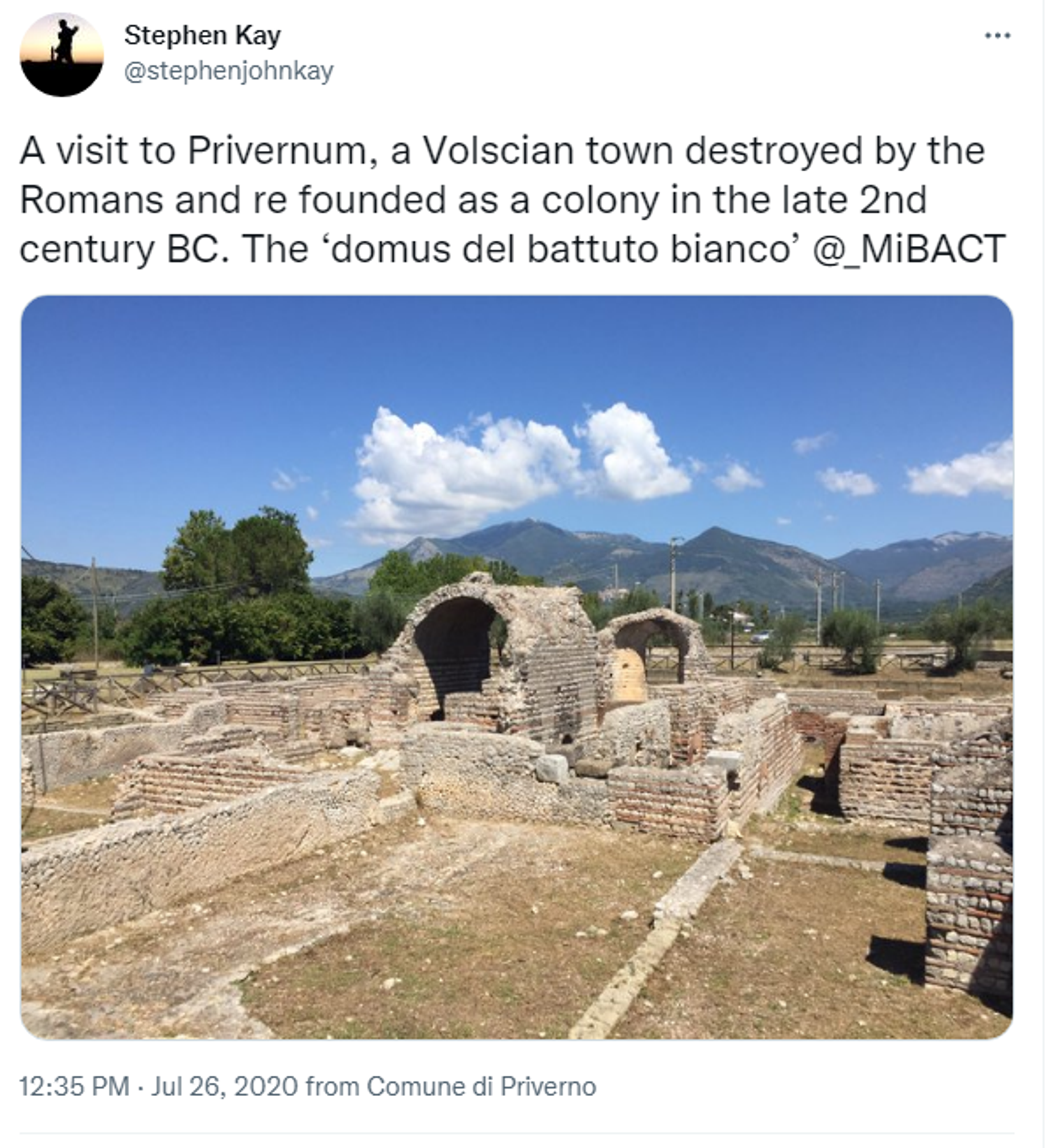

2,000-year-old samples of concrete, taken from a city wall at the archaeological site of Privernum, in central Italy, were analyzed by the study team. The white chunks discovered in the concrete, previously believed to be fragments of poor-quality raw material, in actual fact lent the concrete the ability to heal cracks forming with the onslaught of time.

Referring to the earlier speculation that the chunks, referred to as lime clasts, were just evidence of sloppiness on the part of the Roman builders, study author Admir Masic, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said:

"For me, it was really difficult to believe that ancient Roman (engineers) would not do a good job because they really made careful effort when choosing and processing materials."

Roman texts studied by researchers had appeared to indicate that slaked lime was resorted to as a binding agent in making concrete. Concrete is formed by mixing cement, a binding agent typically made from limestone, water, fine aggregate like sand, and coarse aggregate, such as crushed rock. But the researchers concluded that the chunks, or lime clasts, occurred due to use of quicklime (calcium oxide) when mixing the concrete, rather than or in addition to slaked lime.

The team carried out analysis of the concrete, finding that "hot mixing" explained the concrete's durable characteristics.

"The benefits of hot mixing are twofold. First, when the overall concrete is heated to high temperatures, it allows chemistries that are not possible if you only used slaked lime, producing high-temperature-associated compounds that would not otherwise form. Second, this increased temperature significantly reduces curing and setting times since all the reactions are accelerated, allowing for much faster construction," Masic stated in a news release.

The study conducted an experiment to prove the truth of their findings. They made two samples of concrete, one corresponding to ancient Roman formulas, and the other in line with modern standards. Then they deliberately cracked them and waited for two weeks. By that time, while water seeped through the modern-day type of concrete, the cracks in the concrete made following Roman recipes had "healed."

The results confirmed that lime clasts could dissolve into cracks and subsequently recrystallize after exposure to water in a "self-healing" process that could now be used to producing more long-lasting modern concrete.