Cold War 2.0: Why Current Crisis is Far More Dangerous Than 20th Century’s Long Twilight Struggle

04:00 GMT 05.03.2023 (Updated: 11:38 GMT 05.03.2023)

© Flickr / Dan Century

Subscribe

Longread

Amid the ongoing NATO-Russia proxy conflict in Ukraine, more and more Western media outlets, historians and think tank figures have referred to the crisis as a “new Cold War.” On the anniversary of Winston Churchill’s 1946 Iron Curtain speech, a leading Russian arms control expert explains why the ‘sequel’ to the Cold War is far more dangerous.

March 5 marks another anniversary of Winston Churchill’s 1946 Iron Curtain speech.

In the spring of 1946, as Europe lay in ruins and the WWII Allies the USSR, Britain, and the USA approached the uncertain post-war order, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill traveled to Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri to speak about how, “from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent,” separating the “Soviet sphere” from free nations.

Many Western scholars mark Churchill’s speech as the historical waypoint marking the dawn of the Cold War. Just a month earlier, in February 1946, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin gave a speech in Moscow on the origins of the Second World War and the reasons for the Allies’ victory. He referred to the United States and Britain as great, “freedom-loving countries,” praised their “decisive” role in the defeat of Nazi Germany and militarist Japan, and emphasized that Moscow’s post-war priorities would revolve around reconstruction and peaceful economic development, making no mention of a new confrontation with the West. Stalin warned, however, that monopolistic capital and imperialism, the same forces which brought about the Second World War, may conspire to spark a new conflict.

In the four decades that followed, the Western and Eastern political, economic and military blocs stared one another down at the barrel of a gun, and, eventually, nuclear warhead-tipped missiles.

Tensions eased dramatically from the late 1980s and through the 1990s, as Soviet and Russian leaders Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin took a series of (often unilateral steps) to reduce tensions, increase trust and bring an end to the Cold War, sometimes even at the cost of Russia’s pride and strategic security interests. Both men undoubtedly expected that the West would reciprocate, reject the Cold War mentality and perhaps even dissolve NATO, just as the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact was liquidated in the winter of 1991.

But the US and its allies expressed no desire to do so, and on the contrary began a decades-long push to expand NATO toward Russia’s borders. Assured again and again that the alliance was no longer an anti-Russian bloc, Moscow humbly inquired about whether it too would be allowed to join, but got no answer.

In 2014, having absorbed every former member of the former Warsaw Pact, three post-Soviet republics and several Balkan countries, the West set its sights on Ukraine, one of Moscow’s biggest economic and trade partners, and a country with which Russia shares centuries of common history, cultural, linguistic and other links, thus sparking the current crisis.

The Ukrainian conflict, which Russian officials including President Putin and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov have referred to as a “proxy war” by NATO against Russia, has been characterized as a new Cold War by many Western journalists and scholars, from Foreign Policy contributor Michael Hirsh to historian Niall Ferguson.

Cold War II: Why It’s Worse

“It can be said in principle that we are now in a Cold War, yes. We can say that this is a second iteration of the Cold War, although the nature of these wars is completely different,” says Evgeny Buzhinsky, a retired Lieutenant-General of the Russian Armed Forces, veteran of the first Cold War, and Russia’s top arms control negotiator between 2001 to 2009.

But the current situation “is much worse than it was during the so-called Cold War, that is, in the 1960s, 1970s, and up to the mid-1980s. Back then there was an ideology. There was a socialist camp, and the ‘free democratic West’; this was an ideological confrontation,” the retired officer, who works as chairman of the Russian Center for Policy Research, a Moscow-based think tank, told Sputnik in an interview.

“The USSR had its own socialist camp, had its allies, the Warsaw Pact and its own sphere of influence. The West tried to intervene, but in general, its efforts were quite futile. There was normal trade, within reasonable limits. Of course, there were restrictions on technology exports, but there were no sanctions packages. There was the Jackson-Vanik Amendment [on Jewish emigration from the USSR, ed.] but its impact was very limited. It affected not so much the economy, as I remember, as it meant individual restrictions.”

Today’s crisis is not ideological, Buzhinsky says.

Indeed, both Russia and the Western countries position themselves as market economies and functioning democracies, although Moscow, unlike Washington, does not portend to engage in ‘democracy promotion’ abroad, either by economic, political or military means.

According to the retired general, today’s conflict is an “existential struggle,” with the United States “fighting for its leadership, fighting for its position in the world,” while Russia, for its part, is engaged in a struggle with the West over its “red lines,” security and otherwise.

“The Americans are very fond of the expression ‘American leadership’, and cling to it in every possible way. Russia, of course - in 2007 President Putin clearly indicated that the world of one master, of one world hegemon is unacceptable to us, and we will never agree to it,” Buzhinsky recalled.

“Hence all these color revolutions in Georgia and Ukraine, all of this organized by the Americans. We strongly opposed, but with Georgia we tried to arrest things and announce a reset. Ukraine became the moment of truth. Ukraine for us, I do not like to use the expression ‘red line’, but in principle, mentally for us, Ukraine is of course a red line. Whether or not missiles are placed there. Whether or not it becomes a member of NATO. But the idea that it was going to become a loyal ally of the West and distance itself from Russia is something unacceptable to us,” Buzhinsky said.

Hearing Problems

One of causes of the current crisis, according to the veteran military negotiator, lies in the mentality of US policymakers, their unwillingness to make concessions, and refusal to recognize the other side’s interests.

“It’s very difficult in general to explain something to the Americans. Speaking from my own experience of decades communicating with the Americans, negotiating with them – they are very reluctant to accept any steps which, let’s say, undermine their leading position…Recall how at one time Hillary Clinton said, and I’m paraphrasing, that the US would go to any lengths to prevent the restoration of the Soviet Union. This kind of thinking is where they’re coming from. Therefore, they reject all our attempts to explain that Ukraine for us is more than just a neighboring state,” Buzhinsky said.

“The same was the case when [US Secretary of State Antony] Blinken went to Central Asia to try to explain to these countries that they shouldn’t be friends with Russia, and need to be friends with the United States. The Americans couldn’t give a damn that we have millions of Uzbeks and Tajiks working in Russia…They don’t understand that America is far away. Yes, it can provide some kind of economic assistance, but they think in return all these Central Asian republics should just fully follow their advice and recommendations,” former officer noted.

More Dangerous Than Cuban Missile Crisis

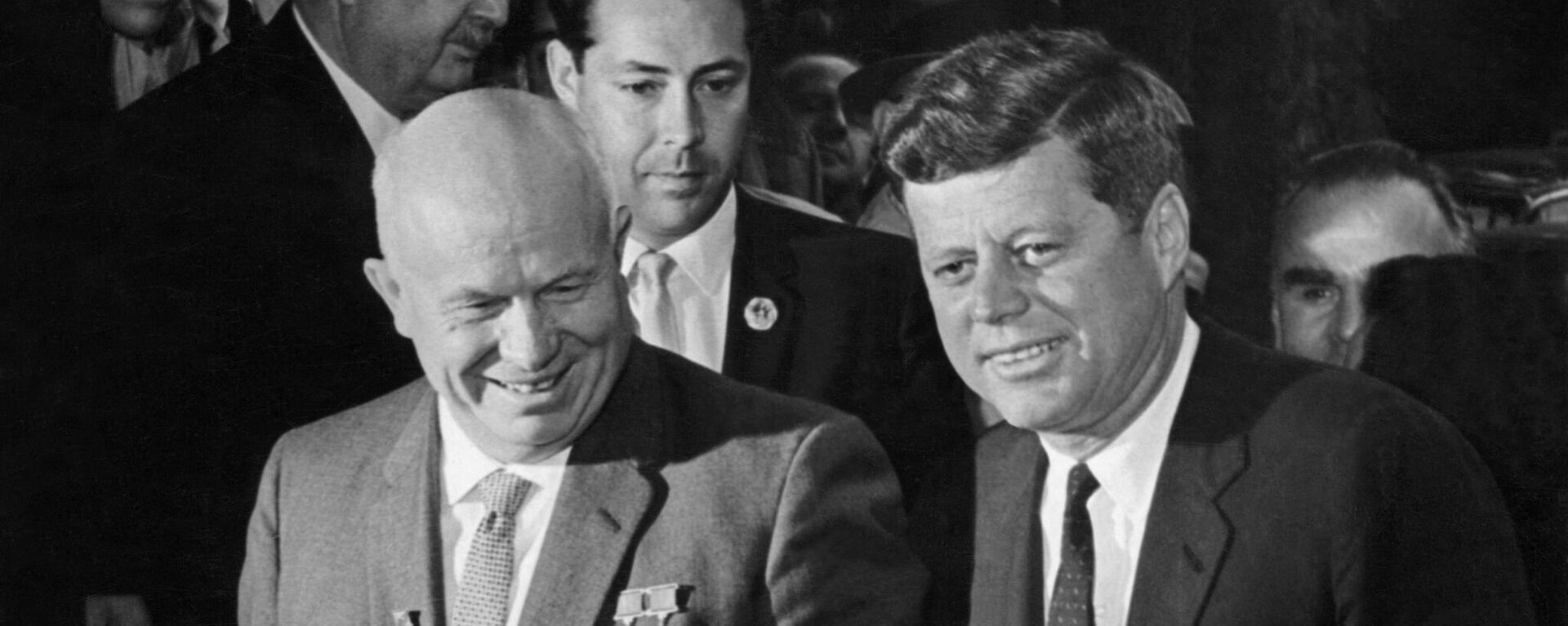

Buzhinsky believes the Ukrainian crisis is far more dangerous than the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, when the world was on the brink of nuclear war.

“It’s more dangerous, for two reasons. Firstly, the outcome of the Cuban Missile Crisis was decided by two people – Kennedy and Khrushchev and their advisors. Today, perhaps if it was just Putin and Biden, things would be easier. But in fact that there are so many ‘assistants’, the Poles, the Balts, the Czechs, who, should Biden and Putin reach an agreement tomorrow, would grit their teeth, but agree, forcibly, because nobody will dare challenge the Americans, especially today. They would keep to themselves, but at the same time spoil everything as much as possible through the European Union.”

The danger of the Ukrainian crisis descending into a global war revolves around the fact that it’s taking place along an “escalation ladder,” with NATO consistently testing Russia’s responses with every delivery of new and more advanced weapons, according to Buzhinsky.

“Right now they’re talking about the delivery of warplanes. The Ukrainians are asking for them. My only hope is in Biden’s common sense – not so much his sanity, given his not very stable mental state, in my opinion, but that instinctively, he remembers the 1970s and 1980s, he grew up during the Cold War, both physically and as a politician. Therefore, he understands how this could all end. But this brazen generation, Jake Sullivan, Antony Blinken, the leadership at the Pentagon, these are people who have never fought anywhere. The bombings of Yugoslavia, Libya, Syria, all these took place without significant losses [for the Americans]. These weren’t wars.”

Deploying Western warplanes in Ukraine is effectively impossible, Buzhinsky says, because aircraft require a large ecosystem of support behind them.

“A plane isn’t a tank. It needs to be serviced before and after every flight. If it’s hit by enemy fire, it has to be repaired, and at a proper airfield, as a rule. For this a base has to be created. Creating this base in conditions of Russian attacks is futile. This means they would have to be based at airfields somewhere in Poland, Romania, Slovakia and other neighboring countries,” the retired general explained. “If a plane takes off from an airfield in Poland, carries out strikes on Russian forces inside Ukraine and returns to this airfield, I am absolutely, 90 percent certain that we would have to carry out strikes against Polish airfields. I think the Americans understand how this might end. That’s the situation.”

The threat of a direct clash between Russia and NATO not only exists today, but “is substantially higher than it was during the Cold War,” Buzhinsky fears.

“Any direct clash between the armed forces of the United States and the Russian Federation would be a global catastrophe, would be mutual annihilation. Because all these fairy tales about a limited nuclear war – the Americans believe it’s possible to indulge in the use of some kind of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe, while they sit at home and watch calmly from behind two oceans. That won’t happen. Putin has already said twice that the response will be strategic. Like I say, we would strike a Polish airfield where Ukrainian F-16s striking at our troops are based, and they would have to think how to respond. Would they take it? That would mean the need to fight. This would mean fighting directly with Russia, and no one would be able to stop the conflict.”

Another problem, Buzhinsky says, is that the current conflict isn’t a Cuban Missile Crisis-style standoff, but an actual hot conflict, a Western-backed proxy conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

“Let’s say Putin and Biden reach an agreement. What can they agree to? Take the four regions which became part of Russia, they are ours. We won’t give them up. What will Biden say? ‘Sure guy, I agree, we’ll stop’? I think that’s unlikely. And the Ukrainians will say ‘we want to fight’, and the Poles and Lithuanians and Estonians will cry ‘how can that be? Where’ s the strategic defeat [of Russia] you promised’? That’s the issue. Unlike the Cuban Missile Crisis, here too many parties are involved in this conflict. In their rhetoric they have driven themselves so far into a corner that it’s now very difficult to agree to anything,” the observer said.

Strategic Dead End

Sputnik also asked Buzhinsky his views on the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), which Russia suspended last month, citing problems with inspections, and US aid to Ukrainian drone attacks on an airbase hosting Russia’s strategic aviation.

“You know, I am not a supporter of exiting agreements. Furthermore, I believe New START is a very good agreement. I started the negotiations on this treaty with the Americans in Rome back in 2008, but unfortunately was unable to finish them. Therefore, I don’t believe we should withdraw. Even before the Ukrainian crisis sentiments were expressed that we should exit, especially in the Duma. ‘Why do we need these agreements?’ was the sentiment. We need them because knowing is better than not knowing. Thanks to the agreements we have an idea, and the Americans have an idea, about one another’s nuclear strategic potential,” the negotiator said.

At the same time Buzhinsky said Moscow’s decision to freeze the agreement is understandable in the present situation, given the fact that the American side has effectively rendered it impossible for Russian inspectors to carry out their work, given sanctions, visa restrictions, the closure of airspace to Russian aircraft, etc.

“The last straw, of course, was the Ukrainian attempt to strike at our airfield in Engels, where our strategic aviation is based. Moreover, these Strizh drones were improved with the help of the Americans. After that, Putin made his completely predictable, reasoned decision.”

As for a new treaty to replace New START, which is set to expire in 2026, the observer believes its prospects are “very obscure” at this stage. Everything the US side might want in the new treaty, including accounting for new types of weapons, non-strategic nuclear weapons, all this is possible, but all of this would take time, years of time, “and the clock is already ticking.” Simply redrafting the existing treaty is also impossible, Buzhinsky believes, because lawmakers in the US Congress wouldn’t accept it.

“And if the Republicans come to power – they in general have a very negative attitude toward any form of arms agreements. They believe they’re to the advantage of the weaker side,” Buzhinsky said.

For these reasons, the arms control expert believes there’s only about a 10 percent chance of a new treaty being realized.

The failure to reach an agreement would hit both sides, and inevitably lead to a new arms race, the retired general says.

“Their Trident missiles, for example, can theoretically hold 10-14 warheads, depending on throw weight, but are restricted to six. In order to know how many there are, you have to come up to the missile, lift up the lid and take a look. You can’t see this from space,” Buzhinsky noted. “Therefore, the Americans could easily double the number of warheads on their missile carriers, so not 1,550, but 3,000. The same is true for us, except we have fewer opportunities for reloading. That’s the risk. And of course, we will proceed from the worst-case scenario, that is, assume that they have not 1,550, but 3,000. An arms race like in the 1960s, when each country accumulated 30,000 warheads, is expensive and unnecessary. But some sort of arms race will take place,” the expert concluded.