https://sputnikglobe.com/20230707/scientists-baffled-by-ancient-supermassive-black-hole-considered-oldest-ever-found-1111733595.html

Scientists Baffled by Ancient Supermassive Black Hole Considered Oldest Ever Found

Scientists Baffled by Ancient Supermassive Black Hole Considered Oldest Ever Found

Sputnik International

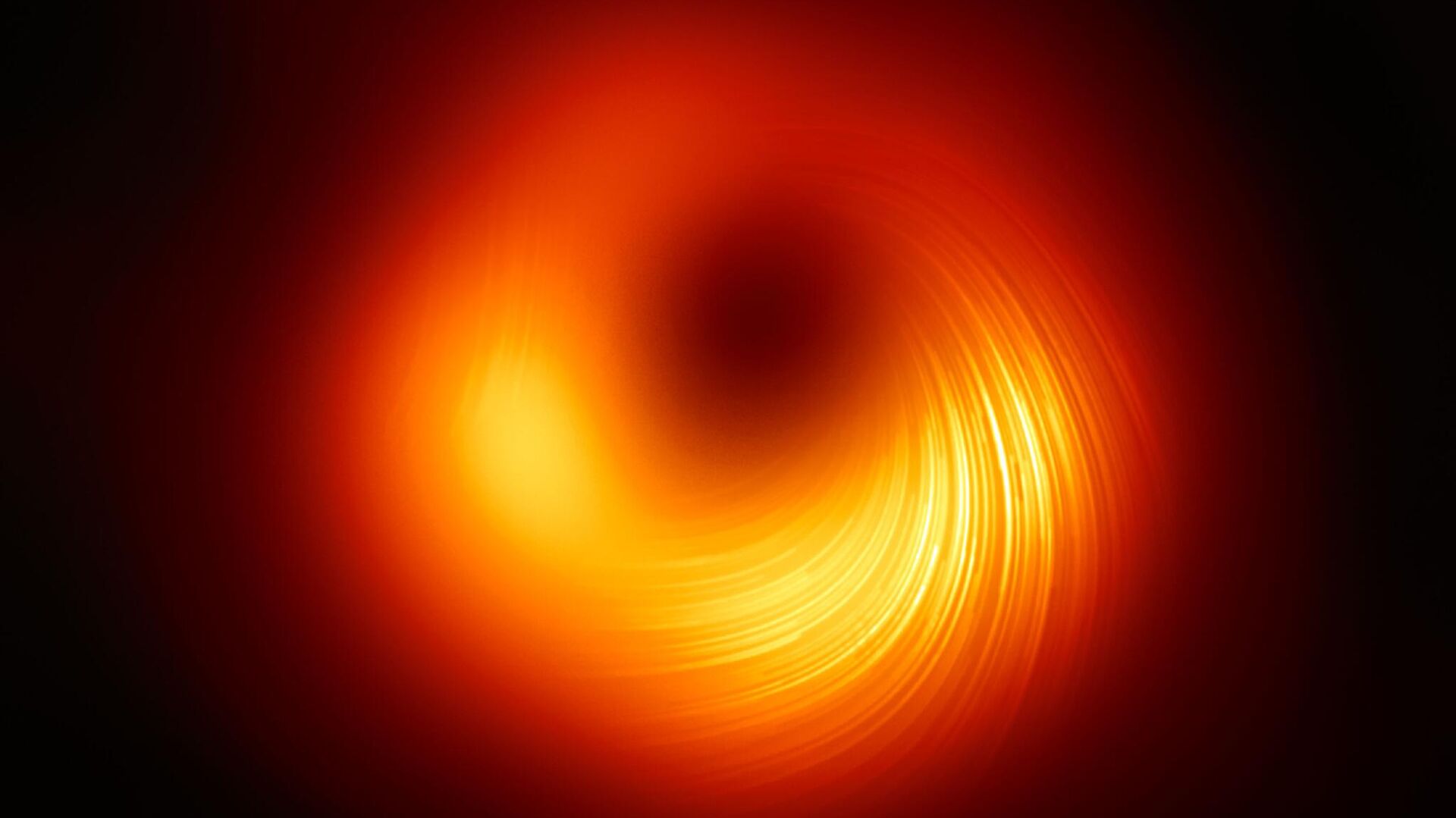

A group of astronomers have discovered the oldest known supermassive black hole, over 13 billion years old. Now, they are struggling to understand how it could have formed so soon after the Big Bang.

2023-07-07T21:34+0000

2023-07-07T21:34+0000

2023-07-07T21:35+0000

beyond politics

james webb space telescope (jwst)

supermassive black hole

astronomy

universe

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/07e7/05/04/1110086580_0:458:2047:1609_1920x0_80_0_0_0143b3af3bf46a29af53756361658f9d.jpg

At the center of the galaxy CEERS 1019 sits a supermassive black hole, as is common in most galaxies, except that this one formed sooner after the Big Bang than any other comparable black hole. According to calculations by a group of astronomers led by Steven Finkelstein of the University of Texas at Austin, it formed just 570 million years after the universe did.In the timeline of the early universe, that period was when the first stars and small galaxies were forming, following a period when most matter was so widely dispersed by the initial Big Bang explosion that it had not yet condensed enough to spark nuclear fusion and cast light into the universe. Yet, somehow, a massive black hole managed to form.Black holes typically form following the death of massive stars; when the fuel that sustains their light has burned out, the core of the star collapses under its own immense gravity, which is so strong it overpowers basic subatomic nuclear forces and falls into an infinitely small spot with gravity so powerful that even light cannot escape from it.Still, this black hole is on the smaller side: while the supermassive black holes that anchor other galaxies can be several billion times the mass of our sun, CEERS 1019 is about 9 million solar masses - an interstellar pipsqueak by comparison. Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, is also quite small - just 4.3 million solar masses.Kocevski led one of three studies in the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) Survey that used the JWST to study the super-distant objects; two others used similar methods and also found ancient black holes and galaxies, some of which were nearly as old as CEERS 1019.Rebecca Larson of the University of Texas at Austin, who underlined another of the studies, noted the data obtained via the JWST is extremely detailed, allowing them to study not just the black hole, but also its host galaxy. In other cases, supermassive black holes often outshine their host galaxy due to the light given off by their consumption of surrounding matter.

https://sputnikglobe.com/20230705/astronomers-watch-as-supermassive-black-hole-begins-feasting-on-nearby-star-1111685267.html

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2023

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

black hole; supermassive; james webb space telescope; astronomy

black hole; supermassive; james webb space telescope; astronomy

Scientists Baffled by Ancient Supermassive Black Hole Considered Oldest Ever Found

21:34 GMT 07.07.2023 (Updated: 21:35 GMT 07.07.2023) A group of astronomers have discovered the oldest known supermassive black hole, over 13 billion years old. Now, they are struggling to understand how it could have formed so soon after the Big Bang.

At the center of the galaxy CEERS 1019 sits a supermassive black hole, as is common in most galaxies, except that this one formed sooner after the Big Bang than any other comparable black hole. According to calculations by a group of astronomers led by Steven Finkelstein of the University of Texas at Austin, it formed just 570 million years after the universe did.

“Until now, research about objects in the early universe was largely theoretical,”

Finkelstein said. “With Webb, not only can we see black holes and galaxies at extreme distances, we can now start to accurately measure them. That’s the tremendous power of this telescope,” he said of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) used in the study.

In the timeline of the early universe, that period was when the first stars and small galaxies were forming, following a period when most matter was so widely dispersed by the initial Big Bang explosion that it had not yet condensed enough to spark nuclear fusion and cast light into the universe. Yet, somehow, a massive black hole managed to form.

Black holes typically form following the death of massive stars; when the fuel that sustains their light has burned out, the core of the star collapses under its own immense gravity, which is so strong it overpowers basic subatomic nuclear forces and falls into an infinitely small spot with gravity so powerful that even light cannot escape from it.

Still, this black hole is on the smaller side: while the supermassive black holes that anchor other galaxies can be several billion times the mass of our sun, CEERS 1019 is about 9 million solar masses - an interstellar pipsqueak by comparison. Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, is also quite small - just 4.3 million solar masses.

"Researchers have long known that there must be lower-mass black holes in the early universe. Webb is the first observatory that can capture them so clearly," said Dale Kocevski of Colby College in Waterville, Maine, in a statement. "Now we think that lower-mass black holes might be all over the place, waiting to be discovered."

Kocevski led

one of three studies in the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) Survey that used the JWST to study the super-distant objects; two others used similar methods and also found ancient black holes and galaxies, some of which were nearly as old as CEERS 1019.

Rebecca Larson of the University of Texas at Austin, who underlined

another of the studies, noted the data obtained via the JWST is extremely detailed, allowing them to study not just the black hole, but also its host galaxy. In other cases, supermassive black holes often outshine their host galaxy due to the light given off by their consumption of surrounding matter.

“Looking at this distant object with this telescope is a lot like looking at data from black holes that exist in galaxies near our own,” she said. “There are so many spectral lines to analyze!”