South Koreans Panic Buy Salt, Seafood Sparked by Fukushima Wastewater Fears

06:21 GMT 10.07.2023 (Updated: 17:01 GMT 31.07.2023)

© AFP 2023 / JUNG YEON-JE

Subscribe

Regardless of efforts to allay public fears by Japanese officials and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), insisting that the upcoming release of a million metric tonnes of treated, highly-diluted radioactive water from the Fukushima nuclear facility into the Pacific Ocean is safe, heightened public anxiety is engulfing South Korea.

Salt has reportedly been vanishing from South Korean supermarket shelves, with the cost of the staple item soaring by about 40 percent since April, according to the country’s salt manufacturing association. Stores nationwide are also said to be stocking up on salt out of concern over an imminent supply crisis, as locals hoard up ahead of the planned radioactive Fukushima water release into the ocean.

On shelves hosting an array of seasonings, such as garlic powder and chili paste, there are visible gaps where salt used to be, according to media reports. One outlet sited a store sign saying: “Salt out of stock.”

Amid the panic-buying, the government opted to release sea salt from its official reserves to stabilize salt prices, which have also been impacted by inclement weather affecting salt production.

“The public doesn’t have to worry about the sea salt supply as the amount of salt provided for June and July will be about 120,000 tons, which is above the average annual production. We ask the public to purchase only the amount you need when buying sea salt,” the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries said in a statement in June.

Seafood is also being snapped up by residents of the country that holds one of the highest production and consumption rates of 'fruits of the sea' in the world. There is a similar rush to buy more other sea-based staples, like seaweed, according to South Korean social media.

A seafood vendor at the Noryangjin Fisheries Wholesale Market in Seoul.

© ANTHONY WALLACE

Stockpiling sea-based food items has been triggered by fears that they may become contaminated after the impending discharge of treated water from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan.

The nuclear disaster at the Fukushima facility occurred on March 11, 2011. The plant was heavily damaged following a magnitude 9 earthquake in the Pacific Ocean, which triggered a massive tsunami that hit the plant, causing three nuclear reactors to melt down.

In the years that followed, some 1.33 million cubic meters of contaminated water ended up being accumulated at the plant - water used to cool the damaged reactors, as well as rainwater and groundwater that seeped into the site. But with the site running out of storage space, Fukushima Daiichi’s operator Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) plans to release this water into the ocean after subjecting the contaminated liquid to a treatment by ALPS processing system meant to remove the majority of radioactive elements. The discharge, which is expected to take place over the course of decades, has been approved by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Noryangjin Fisheries Wholesale Market in Seoul, South Korea.

© AP Photo / Ahn Young-joon

The water discharge plans triggered alarm in Japan itself and in neighboring countries such as China and South Korea. There is a growing list of countries that have banned imports of seafood from the Fukushima region. Fishermen and consumers fear that the treated water, albeit highly diluted, might pollute both salt and the various "ocean delicacies" with hazardous hydrogen isotopes. That said, 78 percent of locals were very or somewhat worried about seafood ending up contaminated, a Gallup Korea survey from June showed.

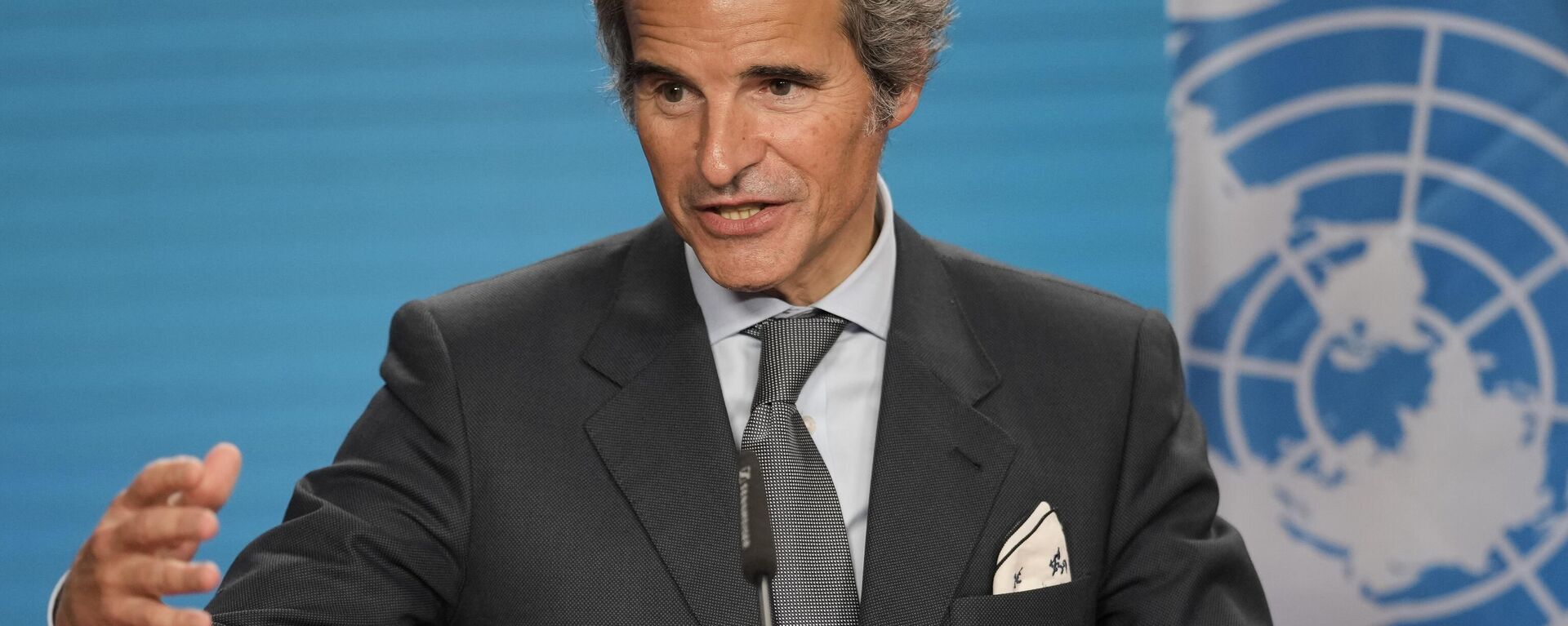

Despite the IAEA attempting to alleviate concerns by releasing a post-safety review report that concluded the dumped wastewater would have a “negligible” impact on people or the environment, worries still persist. IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi acknowledged that public fears were “very logical,” but insisted he was “completely convinced of the sound basis of our conclusions” in a media interview during a visit to Tokyo on July 7.

South Korean protesters hold placards reading "We oppose the dumping of Fukushima contaminated water into the sea" on July 9, 2023.

© AFP 2023 / JUNG YEON-JE

However, a degree of international skepticism regarding the report's findings exists. Chinese officials have warned that it could cause “unpredictable harm.” The Chinese National Nuclear Safety Administration criticized the IAEA report, insisting that it "fails to fully reflect the opinions of experts from all parties involved in the assessment, and the conclusions are not unanimously recognized by all experts." The Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum published an op-ed as far back as in January voicing “grave concerns,” and arguing for more data.

While the South Korean government said last week it would respect the IAEA’s findings, Seoul's residents took to the streets and protested, waving banners that lambasted the wastewater release during Grossi’s visit to the capital.