https://sputnikglobe.com/20230901/mummys-musk-scientists-identify-recipe-for-ancient-egyptian-scent-of-eternity-perfume-1113063515.html

Mummy’s Musk: Scientists Identify Recipe for Ancient Egyptian ‘Scent of Eternity’ Perfume

Mummy’s Musk: Scientists Identify Recipe for Ancient Egyptian ‘Scent of Eternity’ Perfume

Sputnik International

Scientists have uncovered the chemical components of a perfume used in ancient Egyptian death rituals that texts refer to as the “scent of eternity.” They plan to present the musk for all to smell at a forthcoming exhibition.

2023-09-01T21:29+0000

2023-09-01T21:29+0000

2023-09-01T21:27+0000

beyond politics

egypt

max planck institute

ancient egypt

perfume

egyptian mummy

egyptology

https://cdn1.img.sputnikglobe.com/img/107851/09/1078510966_0:79:3127:1838_1920x0_80_0_0_634dfa9a63c139563e76a1444a8a9359.jpg

The paper summarizing their findings and methods was published on Thursday in Scientific Reports, a peer-reviewed journal.Ancient Egyptian mummification rituals and methods were elaborate and systematic, preserving bodies for thousands of years in an effort to ensure their trip to the afterlife was successful. Heavily inscribed with religious and spiritual significance, the process included the removal of the deceased’s internal organs and preservation of their body, as well as decoration and inscription of their caskets with blessings, instructions, and other texts."It embodies the rich cultural, historical, and spiritual significance of Ancient Egyptian mortuary practices."A relatively unknown part of that process has been the use of a perfume which, despite its name, has not persisted to the present - that is, until a team of researchers found some sealed canopic jars that still contained the perfumes inside them.The jars were used to embalm a noble woman named Senetnay around the year 1,450 BCE, during Egypt’s 18th Dynasty - the time when the Egyptian Empire was at the peak of its power and stretched from modern-day Sudan to modern-day Turkiye.The researchers analyzed the liquids using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry, High-Temperature Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry, and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry to separate the individual substances that made up the balms.Researchers found the jars contain a blend of beeswax, plant oil, fats, bitumen, Pinaceae resins, a balsamic substance, and dammar or Pistacia tree resin. The ingredients range from as far away as Southeast Asia.Visitors to the Moesgaard Museum in Højbjerg, Denmark, will get to experience the ancient scent at a forthcoming exhibition, the date for which has not yet been announced.

https://sputnikglobe.com/20230713/hidden-secrets-of-ancient-egyptian-pharaohs-portrait-exposed-thanks-to-x-rays-1111846633.html

egypt

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

2023

News

en_EN

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

Sputnik International

feedback@sputniknews.com

+74956456601

MIA „Rossiya Segodnya“

ancient egyptian mummy; scent of eternity; mummy perfume; egyptology

ancient egyptian mummy; scent of eternity; mummy perfume; egyptology

Mummy’s Musk: Scientists Identify Recipe for Ancient Egyptian ‘Scent of Eternity’ Perfume

Scientists have uncovered the chemical components of a perfume used in ancient Egyptian death rituals that texts refer to as the “scent of eternity,” and plan to present the musk for all to smell at a forthcoming exhibition at the Moesgaard Museum in Denmark.

The paper summarizing their findings and methods was

published on Thursday in Scientific Reports, a peer-reviewed journal.

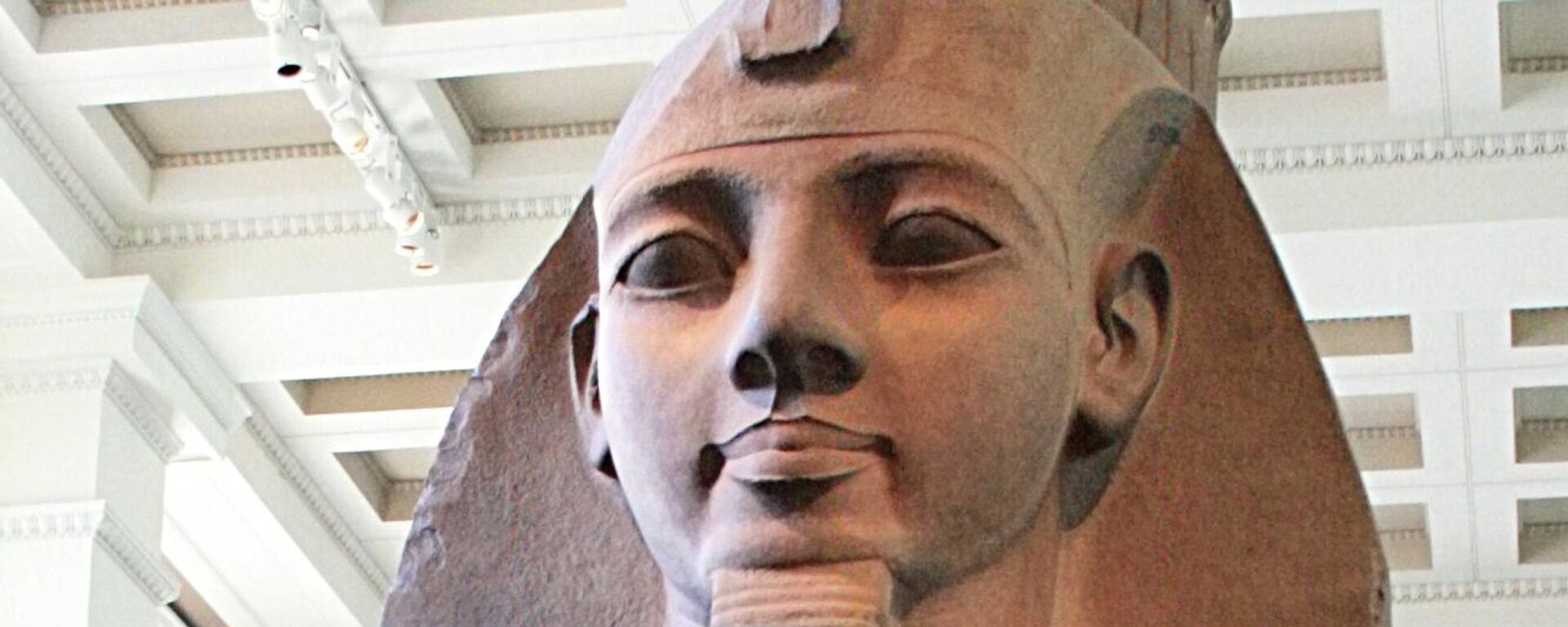

Ancient Egyptian mummification rituals and methods were elaborate and systematic, preserving bodies for thousands of years in an effort to ensure their trip to the afterlife was successful.

Heavily inscribed with religious and spiritual significance, the process included the removal of the deceased’s internal organs and preservation of their body, as well as decoration and inscription of their caskets with blessings, instructions, and other texts.

"'The scent of eternity' represents more than just the aroma of the mummification process," Barbara Huber, an archaeologist from Germany's Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology and the principal co-author of the paper, said in

a news release.

"It embodies the rich cultural, historical, and spiritual significance of Ancient Egyptian mortuary practices."

A relatively unknown part of that process has been the use of a perfume which, despite its name, has not persisted to the present - that is, until a team of researchers found some sealed canopic jars that still contained the perfumes inside them.

The jars were used to embalm a noble woman named Senetnay around the year 1,450 BCE, during Egypt’s 18th Dynasty - the time when the Egyptian Empire was at the peak of its power and stretched from modern-day Sudan to modern-day Turkiye.

The researchers analyzed the liquids using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry, High-Temperature Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry, and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry to separate the individual substances that made up the balms.

“We analyzed balm residues found in two canopic jars from the mummification equipment of Senetnay that were excavated over a century ago by Howard Carter from Tomb KV42 in the Valley of the Kings,” Huber said.

Researchers found the jars contain a blend of beeswax, plant oil, fats, bitumen, Pinaceae resins, a balsamic substance, and dammar or Pistacia tree resin. The ingredients range from as far away as Southeast Asia.

“These complex and diverse ingredients, unique to this early time period, offer a novel understanding of the sophisticated mummification practices and Egypt’s far-reaching trade-routes,” Christian E. Loeben, Egyptologist and curator at the Museum August Kestner in Hannover, Germany, where the jars were kept.

Visitors to the Moesgaard Museum in Højbjerg, Denmark, will get to experience the ancient scent at a forthcoming exhibition, the date for which has not yet been announced.