Tucked between cell blocks, Gitmo’s library is tasked with a noble goal: to provide “intellectual stimulation,” according to prison spokesman Captain Tom Gresback. The most popular books are religious, but some other favorites include Danielle Steele romance novels, the Harry Potter series, and Homer’s “Odyssey,” all housed by a civilian known only as “Milton.”

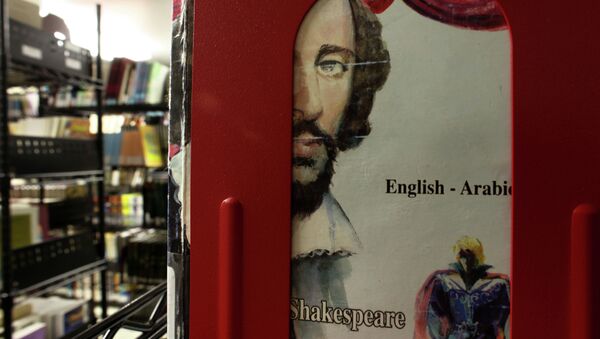

The library holds over 19,000 books, and “all titles available are culturally sensitive, non-extremist in nature and generally non-controversial,” according to Gresback.

Because of this, one new publication will not find its way onto the shelves. “Guantanamo Diary,” the new memoir by Mohamedou Ould Slahi, tells of one inmate’s brutal treatment while serving his ongoing sentence.

“Thanks to the beating I wasn’t able to stand, so [redacted] and the other guard dragged me out with my toes tracing the way and threw me in a truck, which immediately took off,” one passage reads.

Despite its critical acclaim and over 2,500 government redactions, the book will not be cleared for prisoners to browse, Vice reports. This includes Slahi himself, who will most likely be unable to read or hold a copy of his book until he gains his freedom.

“[Slahi] has not seen 'Guantanamo Diary' and I don’t know if he will,” Slahi’s attorney told Vice News.

A district court judge ordered Slahi’s release in 2010, citing a lack of evidence for his arrest, but he still remains in Gitmo.

The diary was finished in 2006, but has only recently been published after a six-year legal fight between Slahi’s attorneys and the U.S. government, who were worried about security concerns.

“[Redacted] was the most violent guard. In building [redacted] the guards performed regular assaults on me in order to maintain the terror,” another excerpt reads.

A native of Mauritania, Slahi fought with mujahedeen rebels in the 1990’s and was then accused by U.S. authorities of being involved in both a plot to blow up Los Angeles International Airport in 1999, and involvement in 9/11. He was taken to Guantanamo in 2002.

He agreed to become an informant in 2003, which gives him special privileges not afforded to other inmates. Among them, the freedom to write.

“A little advertisement,” Slahi once told a military panel of his work. “It is a very interesting book.”