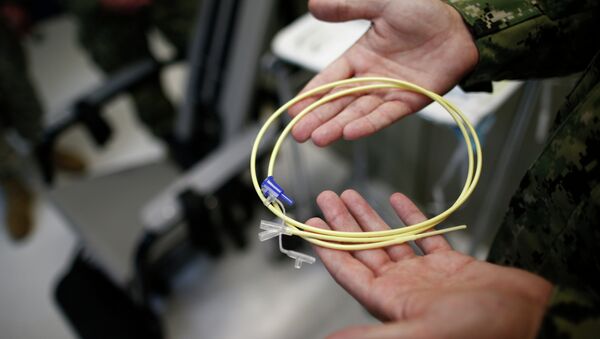

Last year, Guantanamo tapes were reviewed as part of a trial involving Abu Wa’el Dhiab. Those tapes showed the inmate’s forced-feeding, a practice which attorneys said was conducted nearly 1,300 times and caused him physical harm.

"I move my head when they poke me with the tube," Dhiab told his lawyers, according to a 2014 court declaration. "I can’t help it. It hurts too much. Then they hold my head, and it only gets worse. After that I start to resist because I have severe pain in my throat."

Those who have seen the tapes called them disturbing.

"The main reason to see this is because there’s pretty shocking stuff happening right now," Cori Crider, one of Dhiab’s attorneys, said of the tapes.

In an effort to make those videos available to the public, 16 media organizations have filed litigation with the DC Court of Appeals to declassify the tapes.

"There is a public right at stake," David Schultz argued in court, adding the material proves "illegal conduct by government employees."

During the hearing, Justice Department attorneys made a strange – and troubling – argument for why those tapes should remained concealed. Because the documents are classified, they’re exempt from being released to the public, even after being used as evidence in court.

"We don’t think there is a First Amendment right to classified documents," said Catherine Dorsey, attorney for the Justice Department.

That argument would suggest an arguable breach of the government’s separation of powers, whereby the executive branch is telling the judicial branch it has no jurisdiction.

"Your position is that the court has absolutely no authority (to order disclosure), even if the government is irrational?" Judge Merrick Garland asked, adding that the Justice Department may expect similar treatment if it arbitrarily classified the Gettysburg Address.

The government has repeatedly argued that releasing the tapes could harm national security, even after the tapes have been redacted. Dorsey suggested that media organizations would have better luck getting access to the videos through a Freedom of Information Act request, though that process would likely face similar setbacks.

"There’s lots left to be done," Dhiab’s attorney Jon B. Eisenberg told the court. "These videotapes will not see the light of day until the last appeals court [has ruled]," he said, stressing that he would fight for their release at all costs.