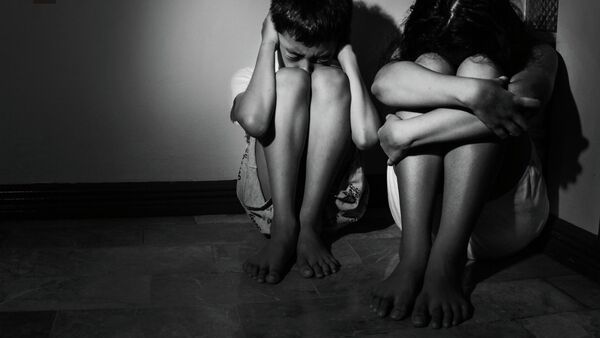

Perhaps it’s a defense mechanism to protect from the enormous emotional toll of such tragedies, or perhaps it’s too hard to relate to it. But one thing is certain – there are people living through these nightmares, and, worst of all, some of them are children. One of the objectives of the United Nations is to make sure children suffer from war, famine and poverty as little as possible. A UNICEF report entitled Impact of Armed Conflict on Children proposed to “claim children as ‘zones of peace’”, but how well is the organization fulfilling the duty to protect them?

The very same report stated:

In Mozambique, after the signing of the peace treaty in 1992, soldiers of the United Nations Operation recruited girls aged 12 to 18 years into prostitution. After a commission of inquiry confirmed the allegations, the soldiers implicated were sent home. In 6 out of 12 country studies on sexual exploitation of children in situations of armed conflict prepared for the present report, the arrival of peacekeeping troops has been associated with a rapid rise in child prostitution.

Deployment of UN and NATO peacekeeping forces has been linked with an increase in child prostitution in Cambodia, Mozambique, Bosnia, and Kosovo. As peacekeepers are seen as the last hope for peace among civilians of troubled nations, such trends are surprising, and not in a good way. Of course, one would have to examine causality – perhaps the events are coincidental. However, at least in some case, reports have proven otherwise. For example, The 2015 report of the Office of Internal Oversight Services of the UN noted:

Evidence from two peacekeeping mission countries demonstrates that transactional sex is quite common but underreported in peacekeeping missions. There is also confusion and resistance to the 2003 bulletin of the Secretary-General with respect to its provision that strongly discourages sexual relations between United Nations personnel and beneficiaries of assistance.

When such events were brought to light, various reports suggest that not only involved personnel received a mere slap on the wrist in one form or another, but that the UN refused to condemn the peacekeepers. The argument is that such public admittance of fault could jeopardize the perception of the United Nations, increase hostility and discourage countries from joining the peacekeeping forces.

Moreover, supporters of peacekeeping missions argue that it’s a “black sheep” situation – the few bad apples should not lead to incrimination of all the participants of the mission. In any case, although the United Nations openly supports children’s rights and freedoms, the latest missions to Haiti and Sudan illustrated that heinous misconduct has not been eradicated, as reports indicate that those in need were coerced into having sex in exchange for aid. It is evident that more scrutiny is required among peacekeeping forces – but, as always, the question remains – who watches the watchmen?