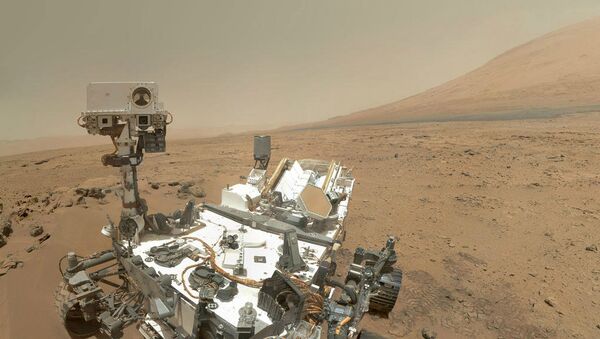

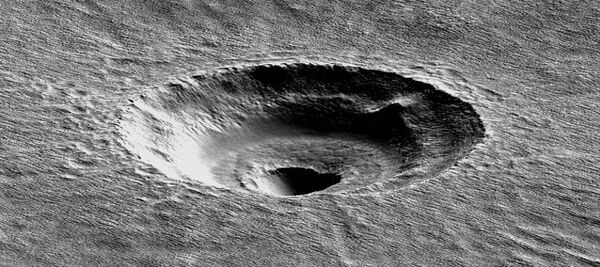

In a paper to be published Friday in the journal Science, the team at the Mars Science Laboratory concluded that water once filled Gale Crater, the landing site for the Curiosity Rover.

The Curiosity rover has been exploring Gale Crater for the past three years. Last year, it arrived at the foothills of Aeolis Mons, a three-mile high mountain dubbed Mount Sharp, and has been exploring the mountain base ever since.

"Observations from the rover suggest that a series of long-lived streams and lakes existed at some point between 3.8 billion to 3.3 billion years ago, delivering sediment that slowly built up the lower layers of Mount Sharp," said Ashwin Vasavada, MSL project scientist. "However, this series of long-lived lakes is not predicted by existing models of the ancient climate of Mars, which struggle to get temperatures above freezing."

John Grotzinger, chair of the Division of Planetary and Geological Sciences at Caltech, says that the mismatch of predictions in Mars’ ancient climate model is similar to that of Earth’s past.

"Aside from the shapes of the continents, geologists had paleontological evidence that fossil plants and animals in Africa and South America were closely related, as well as unique volcanic rocks suggestive of a common spatial origin. The problem was that the broad community of earth scientists could not come up with a physical mechanism to explain how the continents could plow their way through Earth's mantle and drift apart. It seemed impossible. The missing component was plate tectonics," Grotzinger said. "In a possibly similar way, we are missing something important about Mars."

Scientists had speculated Gale Crater was once filled with sedimentary layers before the rover landed on the Red Planet. There were several possible scenarios that suggested the sedimentary deposits were the results of wind or water. The most recent datasets from Curiosity have shown the wet scenarios were correct for the lower portions of Mount Sharp.

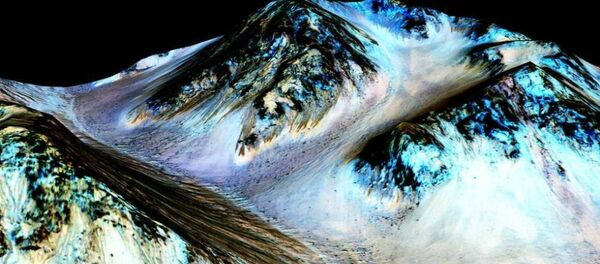

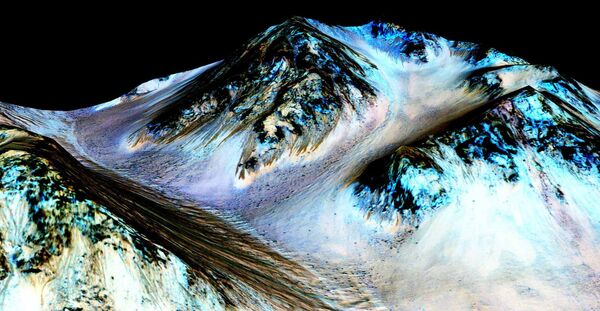

NASA revealed last week that water exists on Mars currently as perchlorate brine. But the filling of at least the bottom layers of Gale Crater were determined to have been from ancient, and not current, water.

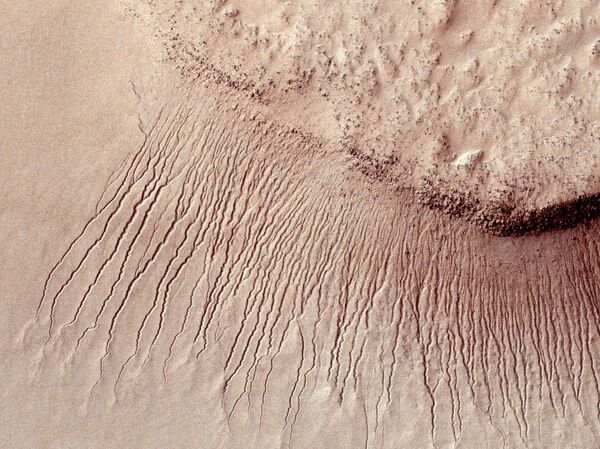

"During the traverse of Gale, we have noticed patterns in the geology where we saw evidence of ancient fast-moving streams with coarser gravel as well as places where streams appear to have emptied out into bodies of standing water," Vasavada said. "The prediction was that we should start seeing water-deposited, fine-grained rocks closer to Mount Sharp. Now that we've arrived, we're seeing finely laminated mudstones in abundance."

"These finely laminated mudstones are very similar to those we see on Earth," said Woody Fischer, professor of geobiology at Caltech and coauthor of the paper. "The scale of lamination—which occurs both at millimeter and centimeter scale—represents the settling of plumes of fine sediment through a standing body of water. This is exactly what we see in rocks that represent ancient lakes on Earth.”

"Paradoxically, where there is a mountain today there was once a basin, and it was sometimes filled with water," Grotzinger added. "Curiosity has measured about 75 meters of sedimentary fill, but based on mapping data from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and images from Curiosity's cameras, it appears that the water-transported sedimentary deposition could have extended at least 150-200 meters above the crater floor, and this equates to a duration of millions of years in which lakes could have been intermittently present within the Gale Crater basin.

As Martian paleoclimatologists develop new models to explain the ancient atmosphere, discoveries and data coming in from Curiosity and other Mars missions will provide more of a backdrop about its history.

Questions that bring answers will bring even more mysteries, as well.